Context:

A huge ice block has broken off from western Antarctica into the Weddell Sea, becoming the largest iceberg in the world and earning the name A-76.

It is the latest in a series of large ice blocks to dislodge in a region acutely vulnerable to climate change, although scientists said in this case it appeared to be part of a natural polar cycle.

Relevance:

GS-III: Environment and Ecology (Climate Change and related issues), GS-I: Geography

Dimensions of the Article:

- What are Ice shelves?

- What are Icebergs?

- About the A-76 Iceberg

- What is Calving?

- Reasons for Calving of A-76

What are Ice shelves?

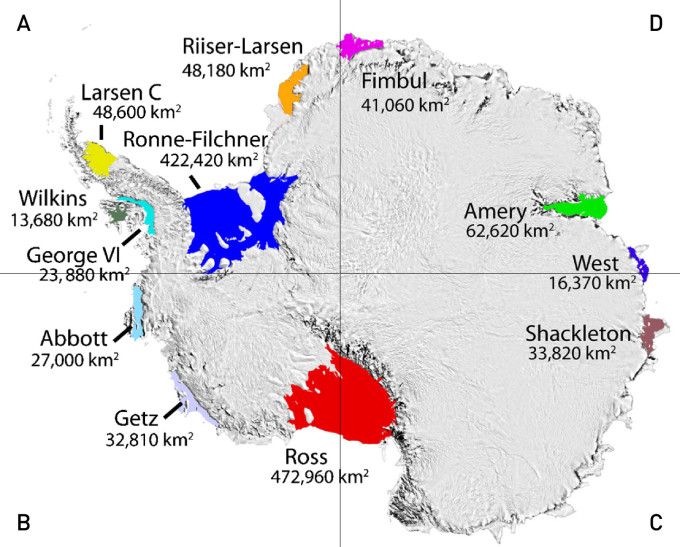

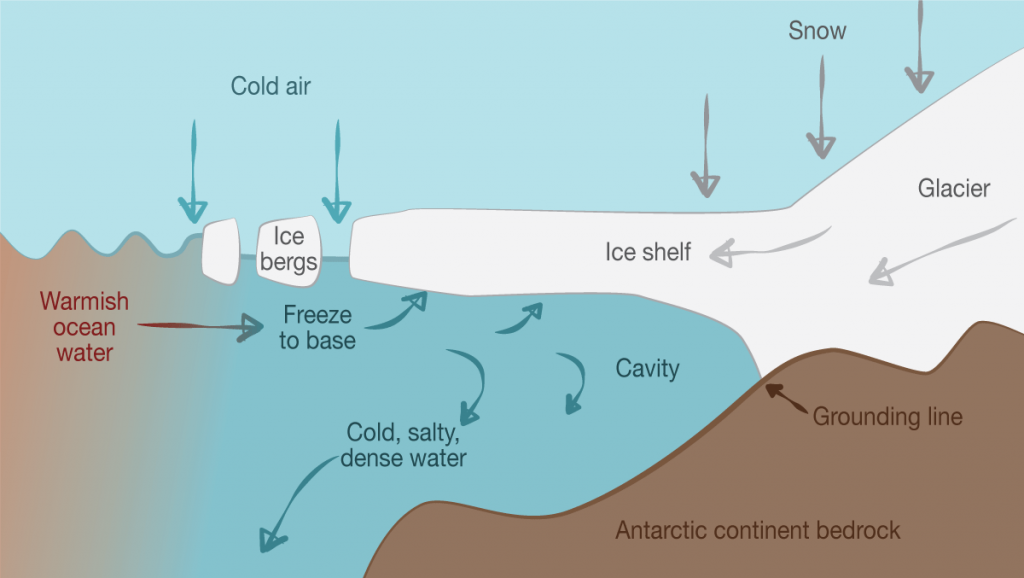

- An ice shelf is a floating extension of land ice. The Antarctic continent is surrounded by ice shelves.

- Ice-shelves cover more than 1.5 million square kilometers in Antarctica – fringing 75% of Antarctica’s coastline, covering 11% of its total area and receiving 20% of its snow.

- The difference between sea ice and ice shelves is that sea ice is free-floating; the sea freezes and unfreezes each year, whereas ice shelves are firmly attached to the land.

- Sea ice contains icebergs, thin sea ice and thicker multi-year sea ice (frozen sea water that has survived several summer ‘melt-seasons’, getting thicker as more ice is added each winter).

Receding Ice-shelves

- Ice shelves around the Antarctic Peninsula are retreating as they are warmed from below by changing ocean currents which thins them and makes them vulnerable.

- During warm summers, ice shelves calve large icebergs – and in some cases, can catastrophically collapse.

What are Icebergs?

- Chunks of ice that float, which are greater than 5 meters across are called “icebergs”.

- Icebergs are floating all around Antarctica after they calve off from tidewater glaciers or ice shelves.

- 90% of the mass of an iceberg is underwater, and only a small part of the iceberg is visible above the water level. S

- Icebergs float in a stable position, with their long axis parallel to the water surface. Elongated icebergs will float on their side.

- Icebergs can have many colours. Blue icebergs are formed from basal ice from a glacier. The compressed crystals have a blue tint. Green and red icebergs are coloured by algae that lives on the ice.

- Stripy icebergs are coloured by basal dirt and rocks, ground up by the glacier and carried away within the glacier ice. Crevasses and other glacier structures may be preserved, giving yet more texture and beauty to the iceberg.

About the A-76 Iceberg

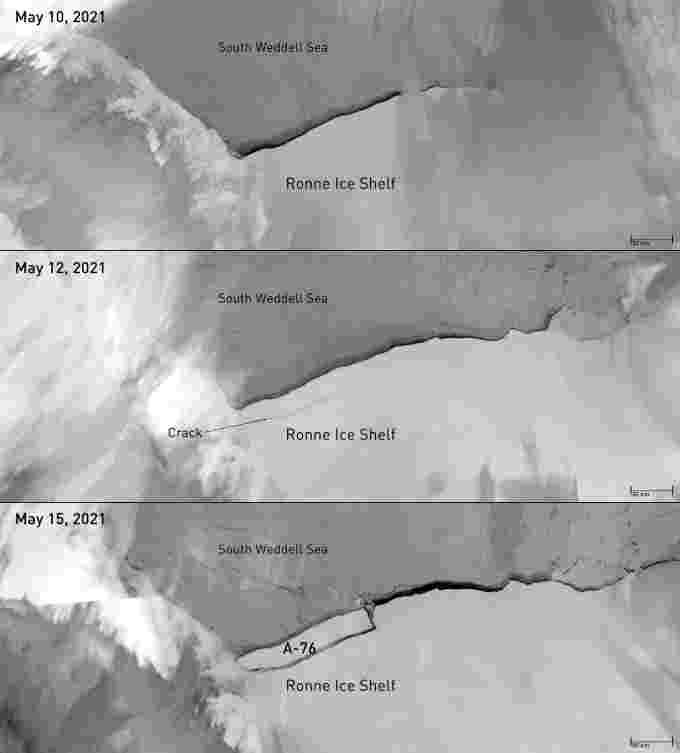

- The A-76 iceberg, measuring around 170 km long and 25 km wide, with an area of more than 4300 sq km calved off from the Ronne Ice Shelf, is now floating in the Weddell Sea.

- A-76 joins previous world’s largest title holder A-23A — approximately more than 3800 sq. km. in size — which has remained in the same area since 1986.

- A-76 was originally spotted by the British Antarctic Survey and the calving — the term used when an iceberg breaks off — was confirmed using images from the Copernicus satellite.

- The Ronne Ice Shelf is located along the southern shores of the Weddell Sea. It is the western part of the larger Filchner–Ronne Ice Shelf, which is split at its leading edge by Berkner Island.

- Icebergs are named by the US National Ice Center, who assigns them a letter-number designation based on what part of Antarctica they originated from and when they formed.

What is Calving?

- Calving is the glaciological term for the mechanical loss (or simply, breaking off) of ice from a glacier margin.

- Calving is most common when a glacier flows into water (i.e., lakes or the ocean) but can also occur on dry land, where it is known as dry calving.

- In lake-terminating (or freshwater) glaciers, calving is often a very efficient process of ablation and is therefore an important control on glacier mass balance.

- Calving is also important for glacier dynamics and ice retreat rates.

Calving processes

- Before calving occurs, smaller cracks and fractures in glacier ice grow (or propagate) into larger crevasses.

- The growth of crevasses effectively divides the ice into blocks that subsequently fall from the snout into an adjacent water-body (where they are known as icebergs).

There are several main calving mechanisms at freshwater glaciers:

- Stretching and crevassing of ice – The faster flow of ice near the terminus (snout or end) due to basal sliding causes the ice to ‘stretch out’, and crevasses to propagate through the glacier.

- Force imbalances at glacier terminus – At a floating glacier terminus, the outward-directed cryostatic pressure (i.e., the pressure exerted by ice) and inward-directed hydrostatic pressure (i.e., the pressure exerted by water) are out of balance, creating a zone of high stress at the ice surface, opening crevasses and promoting calving.

- Undercutting of a terminal ice cliff – Glacier ice at or below a lake waterline often melts at a faster rate than the ice above a lake waterline which will often erode a notch that undercuts the calving ice cliff.

- Buoyant forces at a glacier terminus – Where a glacier surface thins to below the level needed for ice flotation, the margin will become buoyant and lift off the bed causing large bending forces at the grounding line, the growth of large crevasses, and eventually calving.

Reasons for Calving of A-76

- Antarctic ice is increasingly vulnerable to warming ocean waters and changing weather patterns, and for some time, scientists have been raising the alarm regarding the amount of ice being lost from West Antarctica. However, since iceberg calving is part of the natural processes of an ice shelf, we cannot point to an event like this and say that this was caused by climate change.

- An uptick in the frequency of large iceberg formation would be a stronger indication that climate change was a direct factor. What happens after a calving event is significant, as well.

Recently in news: Thwaites Glacier – a.k.a. the ‘Doomsday Glacier’ in Antarctica: Click Here to read more about the Thwaites Glacier threat

-Source: The Hindu