What are Indian labour laws?

In India there are over 200 state laws and close to 50 central laws, yet there is no set definition of “labour laws” in the country.

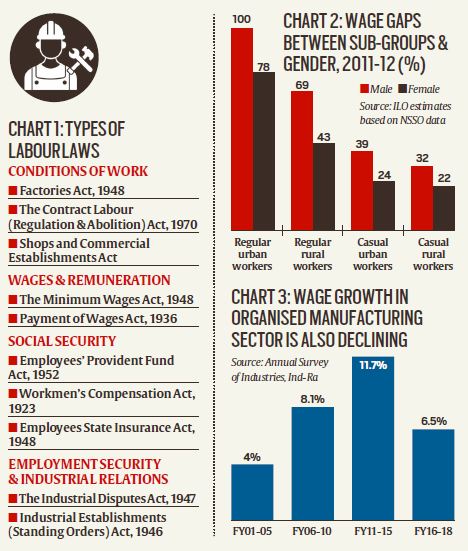

Broadly speaking, they can be divided into four categories –

- Factories Act are to ensure safety measures on factory premises, and promote health and welfare of workers.

- The Shops and Commercial Establishments Act, on the other hand, aims to regulate hours of work, payment, overtime, weekly day off with pay, other holidays with pay, annual leave, employment of children and young persons, and employment of women.

- The Minimum Wages Act covers more workers than any other labour legislation.

- The most contentious labour law, however, is the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 as it relates to terms of service such as layoff, retrenchment, and closure of industrial enterprises and strikes and lockouts.

Why are labour laws often criticized?

- Indian labour laws are often characterised as “inflexible”.

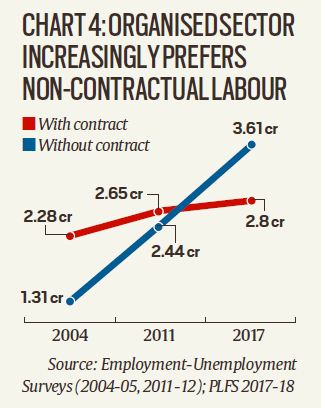

- Even the organised sector is increasingly employing workers without formal contracts.

- This some people argue, has constrained the growth of firms on the one hand and provided a raw deal to workers on the other.

- It can also be argued that there are too many laws, often unnecessarily complicated, and not effectively implemented.

- Moreover, there was always a wide gap between formal and informal wage rates.

Changes to boost employment and spur economic growth

- Theoretically, it is possible to generate more employment in a market with fewer labour regulations.

- However, as the experience of states that have relaxed labour laws in the past suggests, dismantling worker protection laws have failed to attract investments and increase employment, while not causing any increase in worker exploitation or deterioration of working conditions.

- There is already too much unused capacity. Firms are shaving off salaries up to 40% and making job cuts.

- Instead of creating exploitative conditions for the workers, the government should have partnered with the industry and allocated 3% or 5% of the GDP towards sharing the wage burden and ensuring the health of the labourers.