That the archaic labour laws in India need to be amended is beyond debate. They have protected only a tiny section of the labour force, facilitated rent-seeking, and have laid the ground for the casualisation of the labour force, the phenomenon of the missing middle in manufacturing, and the substitution of capital for labour in a capital deficient and labour abundant economy.

Labour in Indian constitution

- Article 246 Labour being in concurrent list, many states and even centre have enacted laws. It led to confusion and chaos

- Article 43A (42nd amendment) – directing state to take steps to ensure workers participation in management of industries.

- Article 23 forbids forced labor, Article 24 forbids child labor (in factories, mines and other hazardous occupations) below age of 14 years.

What are Indian labour laws?

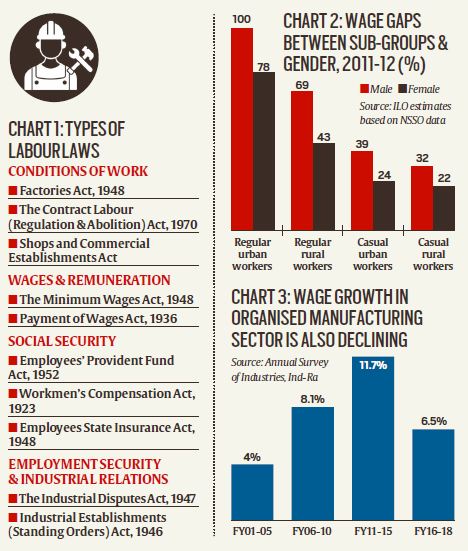

Estimates vary but there are over 200 state laws and close to 50 central laws. And yet there is no set definition of “labour laws” in the country.

The main objectives of the Factories Act, for instance, are to ensure safety measures on factory premises, and promote health and welfare of workers.

The Shops and Commercial Establishments Act, on the other hand, aims to regulate hours of work, payment, overtime, weekly day off with pay, other holidays with pay, annual leave, employment of children and young persons, and employment of women.

The Minimum Wages Act covers more workers than any other labour legislation.

The most contentious labour law, however, is the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 as it relates to terms of service such as layoff, retrenchment, and closure of industrial enterprises and strikes and lockouts.

Challenges with Indian Labour laws

- Organised sector is stringently regulated while the unorganized sector is virtually free from any outside control and regulation with little or no job security.

- Wages are ‘too high’ in the organised sector and ‘too low’, even below the subsistence level in the unorganised sector. This dualistic set up suggests how far the Indian labour market is segmented.

- Social security to organised labour force in India is provided through a variety of legislative measures.

- Workers of small unorganised sector as well as informal sectors remain outside the purview of these arrangements.

- Multiplicity of Archaic Labour Laws: Labour is a concurrent subject and more than 40 Central laws more than 100 state laws govern the subject.

- Trade Union Act, 1926 provide that any seven employees could form a union.

- Multiplicity of trade unions hamper dispute resolution.

- Inter-union rivalry and political rivalries are considered to be the major impediments to have a sound industrial relation system in India.

- Rigid Laws: Job security in India is so rigid that workers of large private sector employing over 100 workers cannot be fired without government’s permission.

- 71% of men above 15 years are a part of the workforce as compared to just 22 percent women- Gender Inequality

- Due to unskilled labour force, employer resort to contract employment to fire them if they are not good.

Essentially, if India had fewer and easier-to-follow labour laws, firms would be able to expand and contract depending on the market conditions, and the resulting formalisation — at present 90% of India’s workers are part of the informal economy — would help workers as they would get better salaries and social security benefits.

What is proposed by states like UP?

UP government decided to bring an ordinance ‘Uttar Pradesh Temporary Exemption from Certain Labour Laws Ordinance, 2020′ to altogether exempt factories and establishments from most labour laws barring for a period of three years.

Only the Building and Other Construction Workers Act, 1996, Workmen Compensation Act, 1923, Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 and Section 5 of the Payment of Wages Act, 1936 (the right to receive timely wages), will be in force in the state.

The changes in the labour laws will apply to both the existing businesses and the new factories being set up in the state.

Similarly, the Madhya Pradesh government has also suspended many labour laws for the next 1000 days. Few important amendments are:

Employers can increase working hours in factories from 8 to 12 hours and are also allowed up to 72 hours a week in overtime, subject to the will of employees.

The factory registration now will be done in a day, instead of 30 days. And the licence should be renewed after 10 years, instead of a year. There is also the provision of penalty on officials not complying with the deadline.

Industrial Units will be exempted from majority of the provisions of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947.

Organisations will be able to keep workers in service at their convenience.

The Labour Department or the labour court will not interfere in the action taken by industries.

Contractors employing less than 50 workers will be able to work without registration under the Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970.

Major relaxations to new industrial units are:

Exempted from provisions on ‘right of workers’, which includes obtaining details of their health and safety at work, to get a better work environment which include drinking water, ventilation, crèches, weekly holidays and interval of rest, etc.

Exempted from the requirement of keeping registers and inspections and can change shifts at their convenience.

Employers are exempt from penalties in case of violation of labour laws.

Reason Behind the Changes in Labour Laws

- States have begun easing labour laws to attract investment and encourage industrial activity.

- To protect the existing employment, and to provide employment to workers who have migrated back to their respective states.

- Bring about transparency in the administrative procedures and convert the challenges of a distressed economy into opportunities.

- To increase the revenue of states which have fallen due to closure of industrial units during Covid-19 lockdown.

- Labour reform has been a demand of Industries for a long time. The changes became necessary as investors were stuck in a web of laws and red-tapism.

Would these changes not boost employment and spur economic growth?

Theoretically, it is possible to generate more employment in a market with fewer labour regulations. However, as the experience of states that have relaxed labour laws in the past suggests, dismantling worker protection laws have failed to attract investments and increase employment, while not causing any increase in worker exploitation or deterioration of working conditions.

Few experts are suggesting that employment will not increase, because of several reasons.

First, there is already too much unused capacity. Firms are shaving off salaries up to 40% and making job cuts. The overall demand has fallen. Which firm will hire more employees right now?

Second, If the intention was to ensure more people have jobs, then states should not have increased the shift duration from 8 hours to 12 hours. They should have allowed two shifts of 8-hours each instead so that more people can get a job.

Third, This move and the resulting fall in wages will further depress the overall demand in the economy, thus hurting the recovery process.

Conclusion:

Any short sighted move now will only end up increasing workers’ vulnerabilities at a time of acute distress, when unemployment is likely to be at all-time highs, and when the national consensus is veering towards providing labourers safety nets. Labour reform for long has framed labour as an adversary, now may be the moment to see it through their prism — this is the only way to make enduring progress.