Context:

After over a year, the stand-off between Indian and Chinese troops in eastern Ladakh shows no signs of resolution. Disengagement has stalled, China continues to reinforce its troops, and talks have been fruitless.

In a recent study published by the Lowy Institute — The crisis after the crisis: how Ladakh will shape India’s competition with China — this writer has argued that the Ladakh crisis offers New Delhi three key lessons in managing the intensifying strategic competition with China.

Relevance:

GS-II: International Relations (India’s Neighbours, India-China relations and Border Issues)

Dimensions of the Article:

- Line of Actual Control

- Background to the India-China Standoff: Story So far

- Major Issues Associated with Disengagement Process

- Three key lessons in the Lowy Institute study

- Conclusion

Line of Actual Control

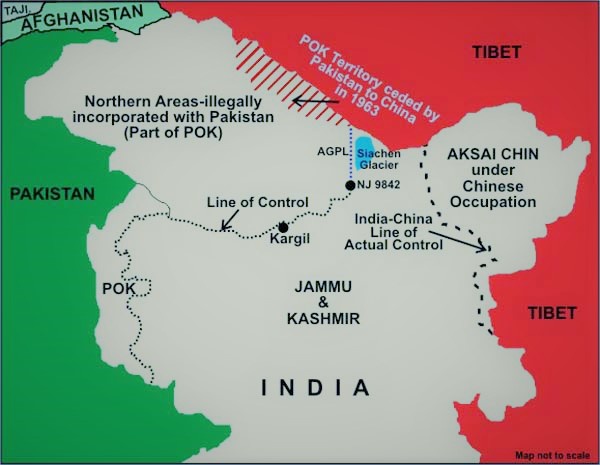

- The disputed boundary between India and China, also known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC), is divided into three sectors: western, middle and eastern.

- The countries disagree on the exact location of the LAC in various areas, so much so that India claims that the LAC is 3,488 km long while the Chinese believe it to be around 2,000 km long.

- The two armies try and dominate by patrol to the areas up to their respective perceptions of the LAC, often bringing them into conflict and leading to incidents such as those witnessed in Naku La in Sikkim earlier this month.

- The LAC mostly passes on the land, but Pangong Tso is a unique case where it passes through the water as well. The points in the water at which the Indian claim ends and Chinese claim begins are not agreed upon mutually.

Background to the India-China Standoff: Story So far

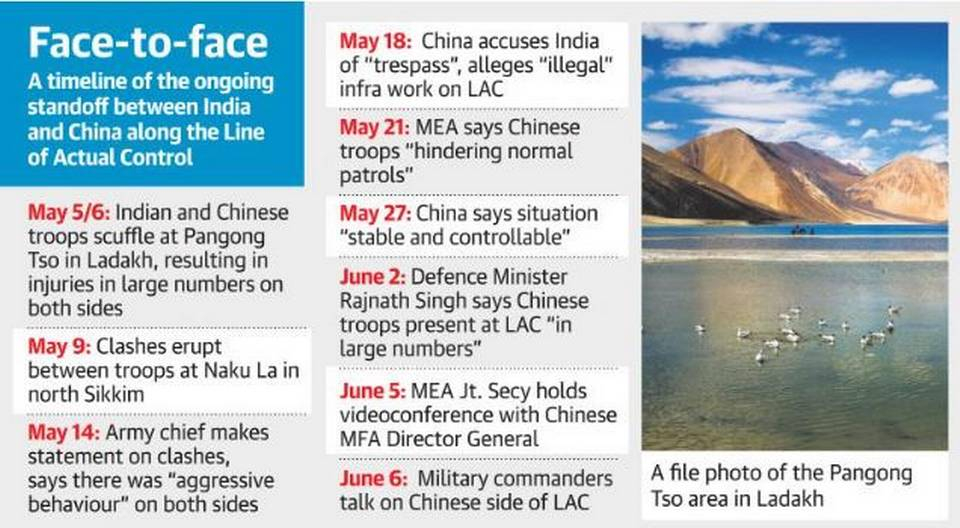

- Tensions between the two sides have continued since May 2020, and serious skirmishes were reported between the Indian Army and PLA soldiers at several points of the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh and Sikkim.

- China is understood to have made significant incursions, and the Indian Army has also bolstered its positions.

- After a series of high-level talks between officials of the two countries, they decided to finally reach an agreement on disengagement at Pangong Lake, which has been at the heart of the recent LAC tensions.

- Both sides agreed to a withdrawal of frontline personnel, armored elements, and proposed the creation of a buffer zone that will put a temporary moratorium on patrolling in the disputed lake. China is also asking India to vacate the heights it occupied in an effective countermove in the Kailash Range.

Major Issues Associated with the Disengagement Process

- The current disengagement is limited to two places on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh viz. north bank of Pangong lake and Kailash range to the south of Pangong. However, there are three other sites of contention on the Ladakh border where the PLA had come in — Depsang, Gogra-Hot Springs and Demchok — and talks will be held to resolve these after the current phase of disengagement is completed.

- The Depsang plains due to their proximity to the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie road, the DBO airstrip, and the Karakoram Pass holds strategic importance for India when it comes to dealing with China. Moreover, the Daulat Beg Oldie road is critical for India’s control over the Siachen glacier.

- Further, for the sake of disengagement at the north bank, China is asking India to withdraw from the important hills it acquired in the Kailash Range. Thus, it raises questions about the wisdom of giving up the only leverage India had against China in Ladakh.

- There are worries that the creation of proposed buffer zones would lie majorly on the Indian side of the LAC, thus converting a hitherto Indian-controlled territory into a neutral zone. At best, these buffer zones can provide a temporary reprieve but are no alternative to the mutual delineation of the LAC and a final settlement of the Sino-Indian boundary.

Three key lessons in the Lowy Institute study

Revamping strategies

- The Indian military’s standing doctrine calls for deterring adversaries with the threat of massive punitive retaliation for any aggression, capturing enemy territory as bargaining leverage in post-war talks.

- However, the study argues that this strategy is not effective as it did not deter China from launching unprecedented incursions in May 2020, and the threat lost credibility when retaliation never materialised.

- Therefore, the first lesson that the study speaks of is that: India should switch military strategies from the angle of punishment to prevention (“Prevention is better than cure”) and deny such incursions before they happen.

- For example: the Indian military’s occupation of the heights on the Kailash Range on its side of the LAC in late August 2020 denied that key terrain to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and gave the Indian Army a stronger defensive position from which it could credibly defend a larger segment of its front line.

- A doctrinal focus on denial will give the Indian military greater capacity to thwart future land grabs across the LAC.

- By bolstering India’s defensive position, rather than launching an escalatory response, such a strategy is also more likely than punishment to preserve crisis stability.

- Over time, improved denial capabilities may allow India to reduce the resource drain of the increased militarisation of the LAC.

Political costs

- The Chinese military’s deployment to the LAC was also large and extremely expensive – China’s defence budget is three to four times larger than India’s, and its Western Theatre Command boasts over 200,000 soldiers.

- The second lesson that the study speaks of is that China would avoid fighting/pushing if the threats are political in nature. China’s military actions do not seem to be deterred by material losses according to the study.

- India successfully raised the risks of the crisis for China through its threat of a political rupture, not military punishment.

- The political risk for China was that if there is an accidental escalation to conflict turning it into a war/war-like situation or if the escalation made India have permanent hostility towards China – then this would become additional burden as China was already facing the instability of its territorial disputes and pandemic response.

- China adjusted its position in the Ladakh crisis because it was responding to the cumulative effect of multiple pressure points — most of which were out of India’s control. Therefore, only coordinated or collective action is likely to be effective. Even large powers such as India will struggle against China when fighting alone.

Indian Ocean Region is key

- In the India-China border, the region is difficult as the terrain as well as the climate is extreme; not to mention, the strength of the military force is also somewhat evenly matched. This means that both sides can have only minor, strategically modest gains at best.

- The third lesson that the study speaks of is that India should consider accepting more risk of losses on the LAC border while actually focussing on long-term leverage and influence in the Indian Ocean Region.

- From the perspective of long-term strategic competition, the future of the Indian Ocean Region is more consequential and more uncertain than the Himalayan frontier.

- India has traditionally been the dominant power in the Indian Ocean Region and stands to cede significant political influence and security if it fails to answer the dizzyingly rapid expansion of Chinese military power.

- The Ladakh crisis, by prompting an increased militarisation of the LAC, may prompt India to defer long-overdue military modernisation and maritime expansion into the Indian Ocean.

- India will have to make tough-minded strategic trade-offs, deliberately prioritising military modernisation and joint force projection over the ground-centric combat arms formations required to defend territory.

Conclusion

- Rebalancing India’s strategic priorities will require the central government, through the Chief of Defence Staff, to issue firm strategic guidance to the military services. This response will be a test not only of the government’s strategic sense and far-sightedness, but also of the ability of the national security apparatus to overcome entrenched bureaucratic and organisational-cultural biases.

- Thus far, India has suffered unequal strategic costs from the Ladakh crisis. Chinese troops continue to camp on previously Indian-controlled land. However, critical evaluation of crisis may help to actually brace India’s long-term position against China.

-Source: The Hindu