CONTENTS

- RBI Dividend Aids Government Finances

- India and the ‘Managed Care’ Promise

RBI Dividend Aids Government Finances

Context:

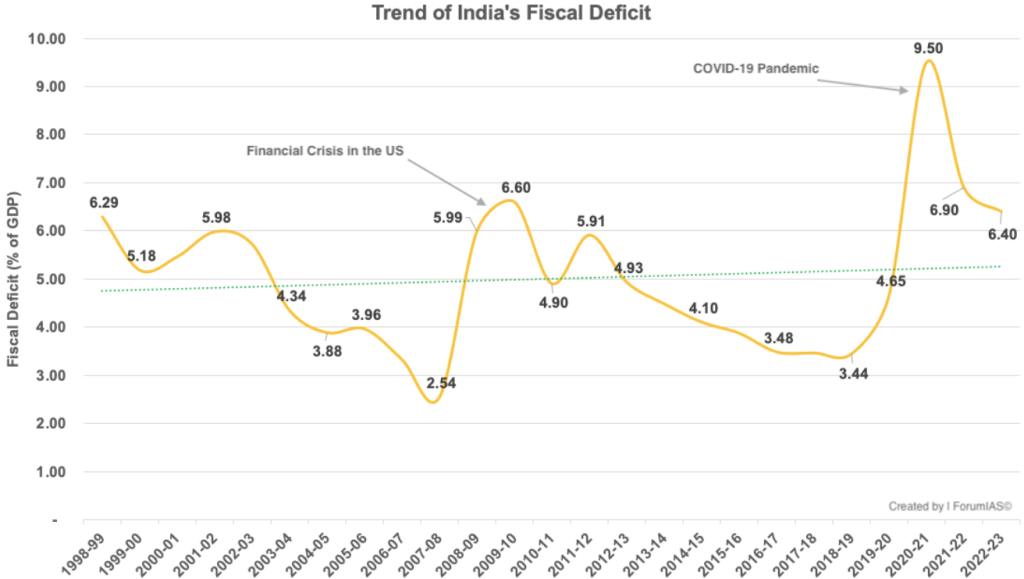

In the amendment to the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act through the Finance Bill 2018-19, based on the recommendations of Dr. N K Singh’s committee, the government committed to achieving a fiscal deficit (FD) of 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by FY 2020-21. However, the COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted the economy, causing revenue to plummet and expenditure to soar in 2020-21, resulting in an FD of 9.1 percent. This necessitated a change in the fiscal glide path.

Relevance:

GS3-

- Banking Sector and NBFCs

- Growth & Development

Mains Question:

The RBI’s dividend transfer provides a substantial fiscal cushion to the cash-strapped Government, but it must be prudent in fiscal management and resource allocation. Discuss. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Government’s Revised Goal:

- In her budget speech for FY 2021-22, Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the government’s revised goal to achieve an FD of 4.5 percent by FY 2025-26.

- The FD decreased from 9.1 percent in 2020-21 to 6.7 percent in 2021-22, 6.4 percent in 2022-23, and 5.8 percent in 2023-24.

- For 2024-25, a target of 5.1 percent was set in the interim budget presented on February 1, 2024. If this target is met, achieving 4.5 percent by 2025-26 should be feasible.

RBI’S Record Dividend Transfer:

- In this context, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has provided significant support to the central government.

- The RBI Board approved a record dividend transfer of Rs 210,000 crore for FY 2023-24, which will be reflected in the central government’s accounts for FY 2024-25.

- This amount is 2.4 times the Rs 87,400 crore dividend transfer for FY 2022-23, which was available for use in 2023-24.

- Comparatively, the Rs 210,000 crore dividend from the RBI for 2024-25 is more than two-and-a-half times the Rs 80,000 crore provisioned in the interim budget.

- This provides an additional cushion of Rs 130,000 crore (210,000 – 80,000), equating to about 0.4 percent of GDP.

- While this should provide the government with substantial leeway in managing its fiscal situation and meeting the 5.1 percent target, there is no room for complacency.

Challenges Ahead:

- First, it’s important to remember that the new goal of 4.5 percent by 2025-26 falls significantly short of the original 3 percent target for 2020-21 set by the FRBM (Amendment) Act 2018.

- The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic was an extraordinary event with a temporary impact, and it is not logical to use it to justify changes in the medium-term fiscal path, especially since the economic situation largely normalized from 2021-22 onward.

- The government should aim for a 3 percent FD target by 2025-26, which indicates there is still a considerable journey ahead.

- Second, we need to consider the RBI’s perspective. Unlike a public sector bank (PSB) or any other public sector undertaking (PSU), the RBI is not a commercial enterprise and thus is not expected to pay dividends. Instead, it operates as a “full-service” central bank.

- In addition to managing currency and payment systems and controlling inflation, the RBI is tasked with managing the borrowings of the Union and State Governments and supervising or regulating banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs). While performing these functions, it generates a surplus.

- The RBI’s income primarily comes from returns on its foreign currency assets (FCA), which include bonds and treasury bills of other central banks or top-rated securities and deposits with other central banks.

- It also earns interest on its holdings of local rupee-denominated government bonds or securities and from short-term lending to banks, such as overnight loans.

- Its expenditures include the costs of printing currency notes, staff salaries, commissions paid to banks for transactions on behalf of the government, and payments to primary dealers for underwriting government borrowings. The surplus is the excess of income over expenditure.

- After making provisions for bad and doubtful debts, asset depreciation, contributions to staff and superannuation funds, and other requirements under the RBI Act (1934), the remaining surplus is paid to the Union Government as per Section 47 of the Act.

Contingency Fund of the RBI:

- Beyond these routine allocations, the financial crisis of the early 90s, when India’s foreign exchange reserves were critically low, highlighted the need for the RBI to be prepared for unexpected financial shocks, ensure stability, and instill market confidence.

- Consequently, the RBI began transferring part of its surplus to a ‘Contingency Fund’, following a committee’s recommendation to build contingency reserves (CR) amounting to 12 percent of its balance sheet.

- In 2013, a panel led by Y H Malegam, an RBI board member, reiterated the importance of building CRs.

- In its 2015-16 annual report, the RBI mentioned developing an “economic capital/provisioning framework” to systematically assess its risk-buffer requirements.

- In 2018, the RBI established the Committee on Economic Capital Framework (ECF) under Dr. Bimal Jalan.

- This committee recommended maintaining a minimum contingency risk buffer (CRB) of 5.5-6.5 percent of the balance sheet. The ECF was to be in place for five years, and the RBI adopted it on August 26, 2019.

- From 2018-19 to 2021-22, the RBI calculated the surplus to be transferred to the Union Government based on a CRB at the lower end of this range, i.e., 5.5 percent.

- For 2022-23, the CRB was raised to 6 percent, and for 2023-24, it was increased to 6.5 percent, the higher end of the prescribed range.

- Despite the higher CRB, the significant increase in the RBI’s interest income from foreign securities and gains from foreign exchange transactions led to a surge in dividend transfers for 2023-24 compared to 2022-23.

- According to the State Bank of India (SBI), these factors contributed 60-70 percent of the income increase from Rs 235,000 crore in 2022-23 to around Rs 375,000-400,000 crore in 2023-24.

- This was due to sharp interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve and other central banks in response to high inflation. However, this situation may not last, as the US Fed plans to lower interest rates from the latter half of 2024, with other central banks likely following suit.

Conclusion:

Even if similar performance is repeated in 2025-26, the RBI should retain more surplus in the CRB as a prudent policy. The central government should not rely excessively on the RBI for managing its fiscal deficit.

India and the ‘Managed Care’ Promise

Context:

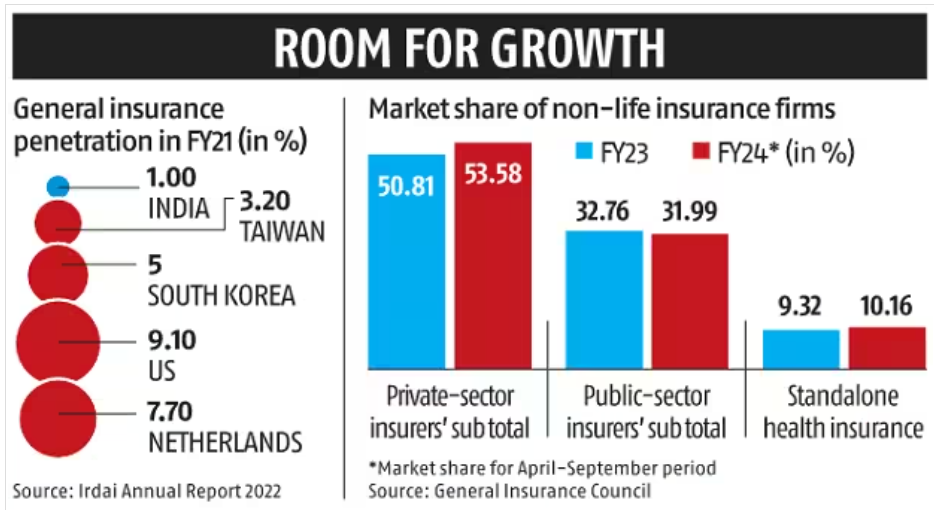

Health insurance as the primary approach to achieving universal health coverage (UHC) now appears firmly established in Indian health policy. Supported by the digital revolution, this approach is paving the way for potential reforms reminiscent of the United States, albeit adapted to avoid its excessive health spending.

Relevance:

GS2- Health

GS3-

- Mobilization of Resources

- Issues Relating to Development

Mains Question:

Discuss the origin and working of a managed care organization (MCO). Can MCOs prove to be beneficial for the broader Indian health-care system, particularly in the context of extending universal health care? Analyse. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Managed Care Organization (MCO):

- Recently, a prominent health-care chain in South India announced its entry into comprehensive health insurance by integrating insurance and health-care provision functions under one entity—essentially an Indian version of a managed care organization (MCO).

- It is an opportune moment to consider whether MCOs could be beneficial for the broader Indian health-care system, particularly in the context of extending universal health care.

The Background:

- MCOs have their origins in some basic prepaid health-care practices in the United States during the 20th century. The movement to mainstream MCOs in U.S. health care gained significant momentum in the 1970s, driven by concerns over health care cost containment.

- Before this, health care was dominated by providers who were generously reimbursed in collaboration with insurers, leading to high premiums that became less attractive to purchasers of health insurance, especially after the economic slowdown post-1970s.

- This situation prompted the merging of insurance and provisioning functions into a single entity, emphasizing prevention, early management, and strict cost control—all within a fixed premium paid by the enrollee.

- Since then, MCOs have evolved through multiple generations and forms, deeply embedding themselves in the health insurance sector.

- Although there is limited robust evidence on their effectiveness in improving health outcomes and prioritizing preventive care, they have been shown to reduce costly hospitalizations and associated expenses.

- In India, since the introduction of public commercial health insurance in the 1980s, the focus has primarily been on indemnity insurance and covering hospitalization costs, despite a substantial $26 billion market for outpatient consultations.

- As discussed by Thomas (2011), health insurance, often secondary to life and general insurance, has seen little innovation and faces high, often unsustainable, operational costs.

A Contrast:

- In an early analysis of the health maintenance organization (HMO)—a type of MCO—experience in developing nations, Tollman et al. identified several key characteristics: MCOs tended to be urban-centric, attracted high-income individuals, and gained traction where the public sector was failing or lacked strong socialist foundations.

- Additionally, successful MCOs required significant financial resources, managerial capabilities, manpower, and a well-off and clearly defined beneficiary base.

- Unlike in the U.S., the development of Indian health insurance has provided few natural incentives for consumer-driven cost control.

- Insurance has mainly targeted the affluent urban population, with informal outpatient practices being widespread and lacking widely accepted clinical protocols.

- While unprofitable operations and unaffordable premiums could theoretically drive cost control, they have not led to a strong systemic push towards managed care.

- Some successful initiatives may come from large health-care brands with a loyal urban patient base and the financial resources to build networks and invest in administrative capacities and infrastructure. However, expecting these private initiatives to significantly contribute to UHC is unrealistic.

- Nevertheless, exploring the managed care approach with cautious and incremental public support could hold promise.

- With an average of three consultations per person per year and a very small share of insurance in outpatient care spending, there is considerable potential to reduce health-care costs through early interventions enabled by comprehensive outpatient care coverage.

- Currently, health insurers have little control over the patient’s journey before hospitalization.

NITI Aayog Report:

- In 2021, NITI Aayog released a report endorsing an outpatient care insurance scheme based on a subscription model, which would generate savings through better care integration.

- The benefits of a well-functioning managed care system can be substantial, offering gains many times over.

- Additionally, its positive impacts—such as consolidating dispersed practices, streamlining management protocols, and embedding a preventive care focus in the private sector—could provide a sustainable solution to the problem of outpatient care coverage in the long term.

- Under the Ayushman Bharat Mission, incentives were introduced to promote the establishment of hospitals in underserved areas to preferentially serve beneficiaries of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY).

- Similar incentives could be designed for MCOs, which would insure and cater to PMJAY patients, along with a private, self-paying clientele, initially on a limited and pilot basis.

- This approach could also be applied to other public sector social health insurance schemes, contributing to increased awareness and expanding the reach of MCOs over time as the self-paying pool grows, thereby expanding the demand base.

Conclusion:

Universal health coverage (UHC) is a complex challenge, and like all complex systems, there is never a single solution to a multifaceted problem. Every solution tends to create new challenges. While MCOs may not be the perfect solution, they can be an integral part of the broader answer that Indian health care needs today.