CONTENTS

- Analysing The India Employment Report 2024

- Understanding India’s Coal Imports

Analysing The India Employment Report 2024

Context:

Titled ‘The India Employment Report 2024’ and authored by the Institute for Human Development/International Labour Organization, this recent report presents a grim outlook for the roughly 7-8 million young individuals entering the workforce annually, with youth comprising nearly 83% of India’s unemployed population.

Relevance:

GS3-

- Employment

- Growth and Development

- Poverty

- Education

- Skill Development

- Human Resource

Mains Question:

With reference to the recently released India Employment Report 2024, discuss the challenges faced by youth entering the Indian workforce annually. What can be done to create better opportunities of employment in a technologically evolving economy like India. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Findings of the Report:

Increasing Proportion of Educated Unemployed Youth:

- The report, unveiled by Chief Economic Adviser V. Anantha Nageswaran, highlights an increase in youth employment and underemployment between 2000 and 2019, which subsequently declined during the pandemic years.

- Of particular concern is the increasing proportion of educated young people among the unemployed, with those having completed secondary education or higher constituting 65.7% as of 2022, up from 35.2% in 2000.

- Even more alarming is the fact that graduates among the youth face an unemployment rate nine times higher (29.1%) than those who are illiterate or have basic literacy skills (3.4%).

- These troubling statistics highlight both the scarcity of jobs suitable for educated young individuals seeking better-paying employment opportunities and deficiencies in the quality of education, which leave a significant portion of educated youth unqualified to meet job requirements.

- Additionally, wages, adjusted for inflation, have either stagnated or declined, exacerbating the challenges faced by the youth in securing decent employment.

- India’s opportunity to capitalize on its substantial youth population for broader socio-economic benefits is rapidly diminishing, as projections indicate that the proportion of young people will decrease to 23% by 2036, down from 27% in 2021.

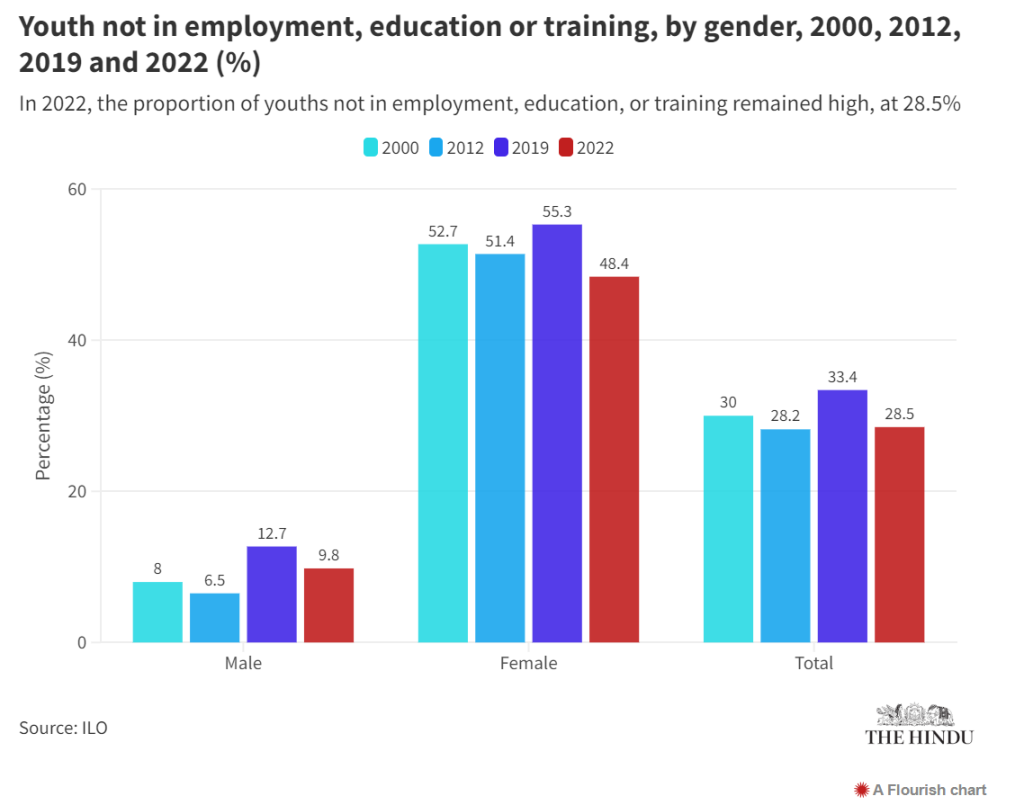

- The authors of the report emphasize the pressing challenges: “Unemployment rates are high, and a significant portion of youth are not engaged in employment, education, or training.

- Furthermore, many employed youths endure poor working conditions, despite the economy’s robust growth. These factors severely hinder the realization of the demographic dividend potential.”

Gender Disparity:

- Additional trends, such as the significant gender disparity in the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR)—with women’s LFPR at 32.8% in 2022, approximately 2.3 times lower than men’s LFPR of 77.2%—and the prevalence of informal employment among 90% of workers, underscore the absence of a cohesive overarching policy vision aimed at securing better employment opportunities for all.

- Contrasting the Chief Economic Adviser’s concerns about the government’s limitations with the primary policy mandate of the U.S. Federal Open Market Committee, which prioritizes “promoting maximum employment along with stable prices,” highlights the need for a focused policy approach.

Employment Landscape:

- The report highlighted paradoxical improvements in India’s job market indicators over the past two decades, despite the persistent challenge of insufficient growth in non-farm sectors and their capacity to absorb workers from agriculture.

- Despite non-farm employment growing at a faster rate than agricultural employment until 2018, the fundamental feature of the employment landscape remained unchanged. Labor from agriculture primarily transitioned to the construction and services sectors.

Informal Employment:

- Additionally, the report emphasized that nearly 90% of workers continue to engage in informal employment. While the proportion of regular employment steadily increased after 2000, it began to decline after 2018.

- The prevalence of livelihood insecurities is widespread, with only a small percentage of individuals covered by social protection measures, particularly in the non-agricultural organized sector.

- Furthermore, there has been a rise in contractualization, with only a minority of regular workers benefiting from long-term contracts.

Lack of Essential Skills:

- Despite India’s sizable young workforce being deemed a demographic dividend, the report pointed out that many lack essential skills.

- A significant portion of youth is unable to perform basic digital tasks, such as sending emails with attachments (75% unable), copying and pasting files (60% unable), and inputting mathematical formulas into spreadsheets (90% unable).

- The report highlighted the significant lack of quality employment opportunities, particularly among young people, especially those with higher education.

- According to the study, many highly educated young individuals are hesitant to accept low-paying and insecure jobs currently available, opting instead to wait for better employment prospects in the future.

Social Inequalities:

- In addressing growing social inequalities, the report underscored that despite affirmative action and targeted policies, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes continue to face obstacles in accessing better job opportunities.

- Despite their higher participation in the workforce due to economic necessity, these groups are more likely to be engaged in low-paid temporary casual wage work and informal employment.

- Moreover, despite improvements in educational attainment across all demographic groups, social hierarchies persist within these groups, as noted in the report.

Way Forward:

- The report underscores five primary policy domains requiring additional attention, which are applicable both broadly and specifically for youth in India:

- Fostering job creation.

- Enhancing the quality of employment.

- Tackling disparities within the labor market.

- Reinforcing skills development and implementing active labor market policies.

- Closing knowledge gaps concerning labor market dynamics and youth employment.

- The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) is poised to impact employment, as highlighted in the report. It suggests that the outsourcing industry in India may face disruption as AI assumes some back-office tasks.

- To harness opportunities for productive employment, investment and regulatory measures are deemed essential in the emerging care and digital economies.

- The report underscores significant challenges posed by gig or platform work, including job insecurity, irregular wages, and uncertain employment statuses for workers.

- Economic policies must prioritize bolstering productive non-farm employment, particularly in the manufacturing sector, given India’s projected addition of 7-8 million youths annually to the labor force over the next decade.

- Additionally, greater support is needed for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs). This support could entail providing tools such as digitalization and AI, alongside adopting a cluster-based approach to manufacturing.

Conclusion:

As the country enters the general election cycle, politicians face the imperative of prioritizing job creation and enhancing the quality of education and training to align with the demands of a technologically advancing economy. These priorities should not only feature prominently in their election campaigns but also guide policy formulation post-election.

Understanding India’s Coal Imports

Context:

As the country braces itself for hot weather, the looming threat of electricity shortages resurfaces. In recent years, the combination of increasingly erratic weather patterns and a rapidly expanding economy has driven a significant surge in electricity demand, presenting a formidable challenge in ensuring reliable supply. However, certain aspects of the discourse surrounding this issue warrant closer examination.

Relevance:

- GS2- Government Policies and Interventions

- GS3- Mineral and Energy Resources

Mains Question:

The discourse around coal shortages in India needs course correction. Comment. (10 Marks, 150 Words).

The Shortage of Domestic Thermal Coal:

- Primarily, the shortage of domestic thermal coal, utilized in electricity generation, is pinpointed as the main culprit behind the electricity deficit. For instance, in August 2023, which witnessed the most pronounced electricity shortage of the year, the situation echoed similar strains experienced during summer months.

- The shortage amounted to approximately 840 million units, primarily attributed to a deficient monsoon leading to heightened demand and diminished supply from certain sources. It’s worth noting that this shortage constituted a mere 0.55% of the demand for that month.

- Furthermore, addressing this shortfall would have required a modest 0.6 million tonnes of domestic coal, whereas coal mines possessed over 30 million tonnes collectively in August and September.

Availability or Logistics- Which is the Main Culprit?

- This disparity underscores that the core challenge lies not in the availability of domestic thermal coal per se, but rather in the inadequate logistical infrastructure for transporting coal to power plants.

- This perspective finds support in a recent advisory from the Ministry of Power, which acknowledges that “supplies of domestic coal will remain constrained due to various logistical issues associated with the railway network.”

- Addressing the logistical hurdles involved would undoubtedly require a considerable amount of time. In the interim, however, the pressing question remains: how should shortages be managed?

Managing Shortages:

Auctions:

- Given that coal currently stands as India’s primary solution to address deficits, the logical response appears to lie in exploring alternative coal sources. Yet, this notion often leads to a common misconception—the assumption that imports represent the sole alternative.

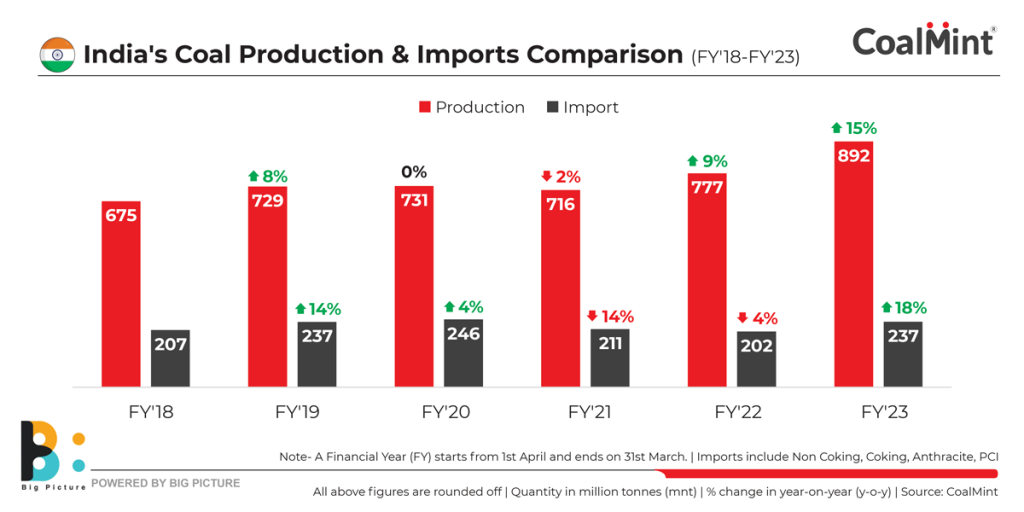

- Coal India Ltd. typically sells approximately 10% of its annual production, equating to roughly 70 million to 80 million tonnes, through spot auctions. Although the price of coal obtained through such auctions surpasses that of coal supplied to many plants, it still remains significantly lower than the price of imported coal.

- Despite the fact that certain plants may not encounter logistical obstacles in acquiring coal from auction sites, they still do not regard auctions as a viable alternative.

Imports:

- The issue of imports further complicates matters. Even if auctions are utilized, some thermal coal imports may be necessary for blending with domestic coal. Consequently, the pertinent question revolves around the extent to which coal plants should rely on imports.

- In response to this dilemma, the Ministry of Power recently issued an advisory to power generators, urging them to continue monitoring their coal stocks until June 2024 and to import coal as needed, up to 6% by weight.

- However, there’s a notable distinction between an advisory and a mandate. While widely perceived as an extension of a “mandate” for importing 6% coal, it’s imperative to recognize that advisories can be conveniently interpreted as mandates by many coal-based generators.

- This interpretation is particularly advantageous for them as any increased costs resulting from coal imports can be passed on to electricity consumers through distribution utilities.

- Therefore, it falls upon electricity regulators, entrusted with ensuring the prudence of electricity costs, to refrain from regarding such advisories as mandates.

- Furthermore, initial analysis indicates that a mere 0.3% additional blending, in addition to the 3.4% of imported coal blended between April and December 2023, could have eradicated all shortages during that period.

- Consequently, the third erroneous narrative emerges, suggesting that 6% coal imports are indispensable when, in reality, it represents merely an upper limit of imports that might be necessary.

- Misinterpreting the advisory as a mandate could carry significant cost implications, particularly considering that coal still accounts for over 70% of India’s electricity production.

- Mandatory blending of 6% imported coal by weight for all coal-based generation, instead of the current blending levels, could inflate the variable cost of coal-based electricity by 4.5%-7.5%.

- Notably, according to the Annual Rating of Power Distribution Utilities report, power purchase costs surged by 15% in FY23, attributable to increased demand, coal imports, and prices of imported coal.

Generation and Geographical Placement:

- Not all power plants operate under the same conditions. Typically, those plants that produce the highest output, known as pit-head plants, are situated near mines, far from ports, and generally do not experience coal shortages.

- Conversely, during periods of heightened demand, plants located farther from mines, which typically generate less power, are more susceptible to shortages.

- Therefore, there is no valid rationale for interpreting the advisory as a mandate to import 6% coal by weight for all plants nationwide.

Conclusion:

Clearly, the discourse surrounding coal shortages in the country requires a shift in direction. It cannot be automatically assumed that coal imports represent the default solution to address shortages. The primary challenge lies in surmounting logistical obstacles that hinder coal delivery to the necessary locations. In the interim, regulatory commissions and distribution utilities must ensure that all coal-based plants remain vigilant regarding the potential for coal shortages and identify the most cost-effective alternative sources— which may not necessarily involve imports— to bridge any gaps. Failure to do so would ultimately burden the consumer with the costs of inefficient coal procurement practices.