CONTENTS

- How Well is India Tapping its Rooftop Solar Potential?

- India’s Diverse Geological Landscape

How Well is India Tapping its Rooftop Solar Potential?

Context:

India’s installed rooftop solar (RTS) capacity surged by 2.99 GW in 2023-2024, marking the highest growth in a single year. By March 31, the total RTS capacity reached 11.87 GW, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. To meet rising energy demands, India must intensify its efforts to enhance RTS potential.

Relevance:

- GS2- Government Policies and Interventions

- GS3- Mineral and Energy Resources

Mains Question:

How equipped are the states in India in tackling rooftop solar capabilities? How can more awareness and efficiency be promoted in this regard?

What is the RTS Programme?

- India launched the Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission in January 2010, aiming to produce 20 GW of solar energy (including RTS) across three phases: 2010-2013, 2013-2017, and 2017-2022.

- In 2015, the government revised this target to 100 GW by 2022, with a 40-GW RTS component, and set yearly targets for each State and Union Territory.

- By December 2022, India had an installed RTS capacity of 7.5 GW and extended the 40-GW target deadline to 2026.

- Despite financial incentives, technological advances, increased awareness, and training boosting RTS installations, much work remains.

- India’s overall RTS potential is about 796 GW. To achieve the target of 500 GW renewable energy capacity, including 280 GW of solar energy by 2030, RTS needs to contribute around 100 GW by 2030.

How Are States Faring?

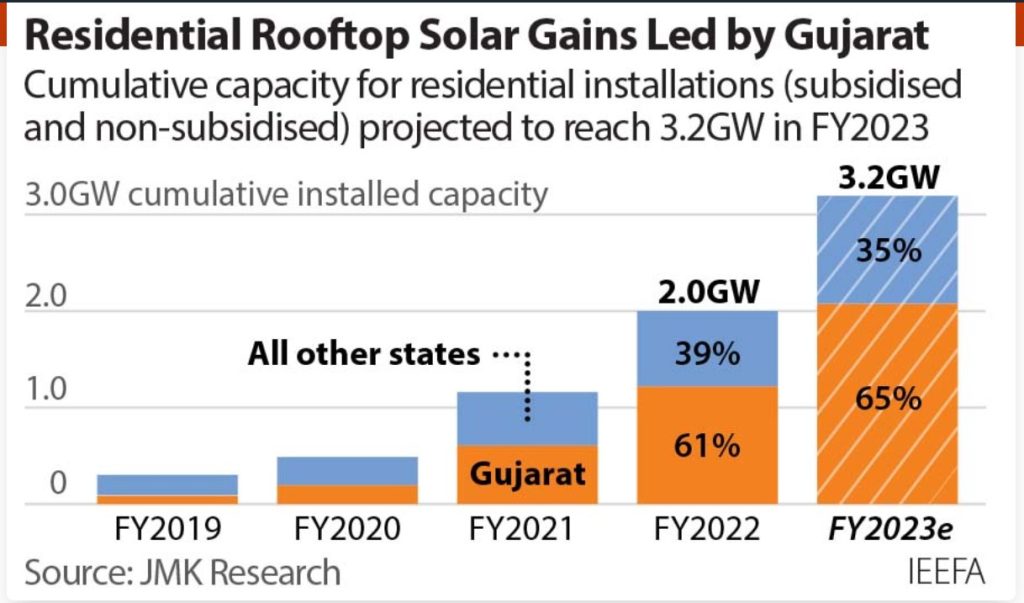

- As of March 31, 2024, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan have made significant progress in RTS capacity, while others lag behind.

- Gujarat, with an installed RTS capacity of 3,456 MW, has benefited from quick approval processes, a large number of RTS installers, and high consumer awareness.

- Maharashtra, boasting 2,072 MW, excels due to robust solar policies and a conducive regulatory environment.

- Rajasthan, with the highest RTS potential at 1,154 MW, has seen growth due to streamlined approvals, financial incentives, and promotion of RTS through public-private partnerships.

- Kerala, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka, with capacities of 675, 599, and 594 MW respectively, have performed reasonably well.

- However, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Jharkhand, among others, have yet to fully explore their RTS potential, facing challenges such as bureaucratic hurdles, inadequate infrastructure, and lack of public awareness.

Pradhan Mantri Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana:

- The ‘Pradhan Mantri Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana‘ is a flagship initiative aimed at equipping one crore households with rooftop solar (RTS) systems, providing them with up to 300 units of free electricity each month.

- With an average system size of 2 kW per household, the total RTS capacity will increase by 20 GW.

- The scheme has a financial outlay of ₹75,021 crore, which covers financial assistance for consumers (₹65,700 crore), incentives for distribution companies (₹4,950 crore), incentives for local bodies and model solar villages in each district, payment security mechanisms, capacity building (₹657 crore), and awareness and outreach (₹657 crore).

- Additionally, the scheme promotes the adoption of advanced solar technologies, energy storage solutions, and smart grid infrastructure.

How can we Ensure RTS Growth?

- Creating awareness is crucial for getting consumers to adopt RTS. Additionally, RTS must be economically viable for households.

- Although government subsidies help, multiple low-cost financing options are necessary.

- Recently, more banks and non-bank financial companies have begun offering RTS loans. Access to these low-cost loans should be as straightforward as obtaining a bike or car loan.

- Promoting research and development in solar technology, energy storage solutions, and smart-grid infrastructure can reduce costs, enhance performance, and improve the reliability of RTS systems.

- Investments in training programs, such as the ‘Suryamitra’ solar PV technician program launched in 2015, along with vocational courses and skill development initiatives, will help build a skilled workforce.

Conclusion:

As the scheme’s implementation progresses, net-metering regulations, grid-integration standards, and building codes should be reviewed and updated to address emerging challenges and ensure smooth implementation.

India’s Diverse Geological Landscape

Context:

India’s landscape, ranging from the world’s highest peaks to low-lying coastal plains, showcases a diverse morphology that has evolved over billions of years. Across various regions, we find an array of rocks, minerals, and unique fossil assemblages. These geological features and landscapes reveal the spectacular ‘origin’ stories rooted in scientific interpretations rather than mythology.

Relevance:

GS1-

- Indian Culture – Salient aspects of Art Forms, Literature and Architecture from ancient to modern times.

- Changes in critical geographical features (including water-bodies and ice-caps) and in flora and fauna and the effects of such changes.

Mains Question:

Discuss the initiatives taken by the Indian government in the area of geo-conservatism. How efficient have been these steps and what are the associated challenges? (15 Marks, 250 Words).

India’s Geological Past:

- India’s turbulent geological past is recorded in its rocks and terrains, representing a significant part of our non-cultural heritage.

- The country offers numerous examples of such geo-heritage sites, which serve as educational spaces where people can gain essential geological literacy.

- This is crucial given India’s generally poor regard for this legacy.

Limited Progress in Geo-Conservation:

- Geological conservation aims to preserve the best examples of India’s geological features and events so that current and future generations can appreciate some of the world’s best natural laboratories.

- Despite international advancements in this field, geo-conservation has not gained much traction in India.

- The extent of these activities is significant, with stone-mining operations covering more than 10% of India’s total area.

- These geological features provide insights into the formation of the land we are familiar with and are part of an evolutionary history that has shaped the Indian terrain.

- Ironically, while we reach out to Mars in search of evidence for early life, we simultaneously destroy precious proof that exists in our own backyard.

- How many of us are aware of the little-known Dhala meteoritic impact crater in Shivpuri, Madhya Pradesh? This crater, dating back between 1.5 billion and 2.5 billion years, is evidence of a celestial collision during the early stages of life.

- The more famous Lonar crater in Buldhana district, Maharashtra, was initially dated to be around 50,000 years old, but recent studies suggest it originated around 576,000 years ago.

Recognizing the Importance of Shared Geological Heritage:

- The significance of our planet’s shared geological heritage was first acknowledged in 1991 at a UNESCO-sponsored event, the ‘First International Symposium on the Conservation of our Geological Heritage’.

- Delegates at this event in Digne, France, endorsed the idea of a shared legacy: “Man and the Earth share a common heritage, of which we and our governments are but the custodians”.

- This declaration anticipated the creation of geo-parks to commemorate unique geological features and landscapes within their territories and to educate the public about geological importance.

Development of Geo-Heritage Sites Worldwide:

- Many countries, including Canada, China, Spain, the United States, and the United Kingdom, have developed geo-heritage sites as national parks.

- UNESCO has also provided guidelines for the development of geo-parks.

- Numerous countries have enacted legislation to build, protect, and designate geo-parks.

- Europe celebrates its geological heritage across 73 zones, and Japan offers another exemplary model of such conservation.

- Today, there are 169 Global Geoparks across 44 countries. Thailand and Vietnam have also implemented laws to conserve their geological and natural heritage.

- Although India is a signatory to such initiatives, it lacks legislation or policy for geo-heritage conservation.

Need for Sustainable Conservation Approaches in India:

- This situation calls for sustainable conservation approaches similar to those formulated for biodiversity protection.

- The Biological Diversity Act was implemented in 2002, resulting in 18 notified biosphere reserves in India.

- A recent incident involving a cliff in Varkala, Thiruvananthapuram district, Kerala, illustrates this issue. The cliff, composed of rocks deposited millions of years ago and declared a geological heritage site by the GSI, had part of it demolished by the district administration to save unauthorized structures, citing landslide hazards.

- Many such features across the country face similar threats to their survival.

Half-Hearted Measures:

- The Government of India has made some attempts to address these concerns, though not with full commitment. In 2009, a National Commission for Heritage Sites Bill was introduced in the Rajya Sabha but was only half-heartedly pursued.

- Despite being referred to the Standing Committee, the government ultimately withdrew the Bill for unspecified reasons.

- More recently, in 2022, the Ministry of Mines drafted a Bill for the preservation and maintenance of geoheritage sites, but there has been no further progress.

- According to the annexure to the Draft Geoheritage Sites and Geo-relics (Preservation and Maintenance) Bill, 2022, “In sharp contrast to the well-laid-out protection and conservation measures for archaeological and historical monuments and cultural heritage sites, India does not have any specific and specialized policy or law to conserve and preserve geoheritage sites and geo-relics for future generations.”

Conclusion:

India urgently needs to take the following steps: first, create an inventory of all potential geo-sites in the country (in addition to the 34 sites identified by the GSI); second, develop geo-conservation legislation similar to the Biological Diversity Act 2002; and third, establish a ‘National Geo-Conservation Authority’ akin to the National Biodiversity Authority, with independent observers. This authority should avoid creating excessive bureaucracy and should not encroach on the autonomy of researchers and academically-inclined private collectors.