CONTENTS

- Plug Leakages in Fertiliser Subsidy

- Driving Innovation: Role of Intellectual Property in India

Plug Leakages in Fertiliser Subsidy

Context:

Recently, the government announced its plans to improve the administration of fertilizer subsidies and reduce leakages and diversions, building on the success of neem-coated urea. It aims to pilot a revised direct benefit transfer (DBT) system in several districts, linking farmers’ land holdings with their nutrient consumption. This proposal, initially suggested in 2020, is being revived.

Relevance:

GS3-

- Agricultural Resources

- Mobilization of Resources

- Direct & Indirect Farm Subsidies

Mains Question:

The real reason behind the leakage in fertiliser subsidy is the control of MRP at an artificially low level due to which dubious players have a huge incentive to divert it. Examine in the context of the working dynamics of fertiliser subsidies in India. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Urea Subsidy:

- To keep urea—a key fertilizer providing nitrogen (N) and accounting for nearly half of India’s total fertilizer consumption—affordable for farmers, the Union Government controls its maximum retail price (MRP), maintaining it at a low level despite the higher production, import, and distribution costs.

- The government reimburses the excess cost over the MRP to manufacturers/importers as a subsidy, which varies based on individual unit costs. Despite rising costs, the MRP of urea has remained virtually unchanged since 2002, with increased subsidies covering cost escalations.

Subsidies in Other Fertilisers:

- For fertilizers supplying phosphate (P) and potash (K)—the other half of India’s fertilizer consumption—there is a uniform subsidy per nutrient under the Nutrient Based Subsidy (NBS) Scheme.

- Manufacturers can set the MRP but must reduce it by the subsidy amount. Despite unchanged subsidies, rising costs have led to increasing MRPs.

- The Department of Agriculture and Cooperation (DoAC), in consultation with states, assesses fertilizer needs for each cropping season—kharif (April to September) and rabi (October to March).

Monitoring the Leakage in Subsidies:

- The Department of Fertilisers (DoF) creates a supply plan to meet all urea requirements from domestic production and imports. States allocate and track urea distribution to the district level.

- The DoF has also developed a mobile and web application, the Fertiliser Monitoring System (m-FMS), which provides stock, sale, and receipt information down to the last retail point.

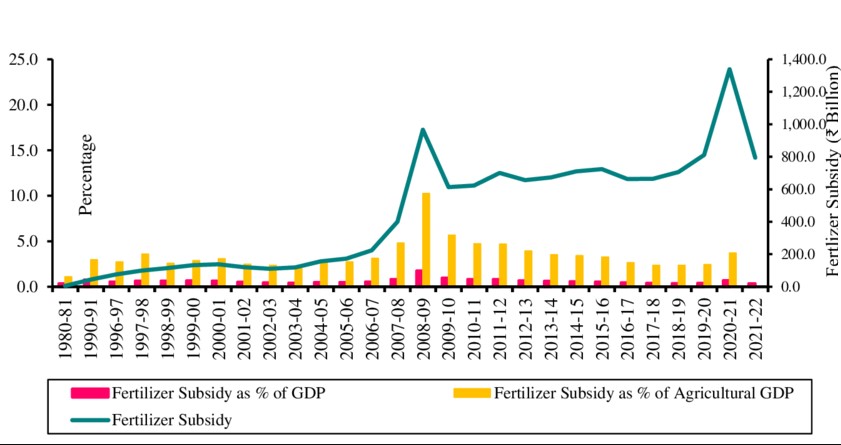

- Annually, the total expenditure on fertilizer subsidies—covering both urea and non-urea fertilizers—is around Rs 200,000 crore.

- The Economic Survey 2015-16 highlighted significant leakage and diversion issues: 24% of the subsidy went to inefficient producers, 41% was diverted to non-agricultural uses or smuggled to neighboring countries, and 24% was used by larger, wealthier farmers.

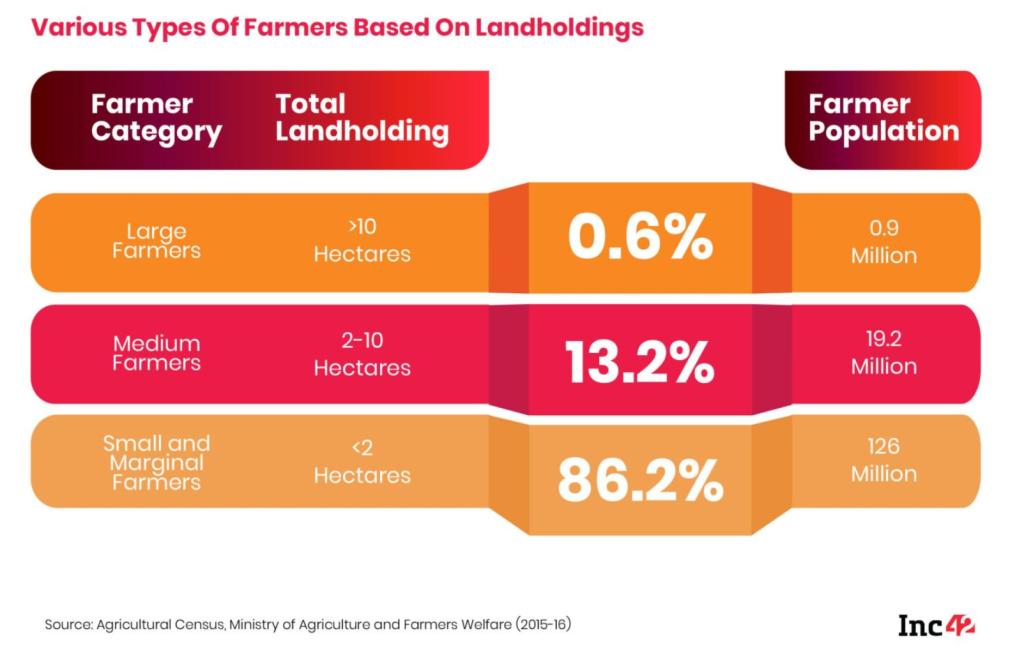

- Consequently, only 11% of the subsidy actually reached small and marginal farmers, who make up about 86% of the farming population.

Causes Behind this Leakage:

- At a fundamental level, leakages are embedded in the design of the fertilizer subsidy administration.

- The government requires manufacturers to sell fertilizers at a low price, deemed affordable for farmers.

- After selling at this price, manufacturers claim the excess cost of supply as a subsidy from the government.

- Although this subsidy could be given directly to farmers, for instance by depositing the money in their bank accounts, successive governments have preferred routing it through manufacturers.

- This method is more convenient for the government, as it involves dealing with a few manufacturers rather than millions of farmers. However, this system has a significant downside.

- Since the subsidy is embedded in the low MRP, the subsidized fertilizer must reach the farmer and be used for crop cultivation. If it doesn’t, the subsidy benefits whoever intercepts the fertilizer.

- After leaving the factory or port (for imports), fertilizers travel long distances by rail or road to district storage points, and then to retail outlets for sale to farmers.

- Initially, manufacturers received most of the subsidy upon dispatching the fertilizer from the factory (since 1977 for urea and 1980 for other fertilizers).

- Over time, the government changed this to disbursing 95% of the subsidy to urea producers and 85% to non-urea producers upon the fertilizer’s receipt at a district railhead or approved warehouse. The remaining 5% or 15% was paid upon confirmation of sales to farmers by the states.

- In March 2018, the government made subsidy disbursement to manufacturers contingent upon actual sales to farmers, recorded on point-of-sale (PoS) machines.

- However, this does not guarantee against diversion, as anyone—including non-farmers—can purchase fertilizer in any quantity through PoS machines by simply providing their unique identity or Aadhaar number.

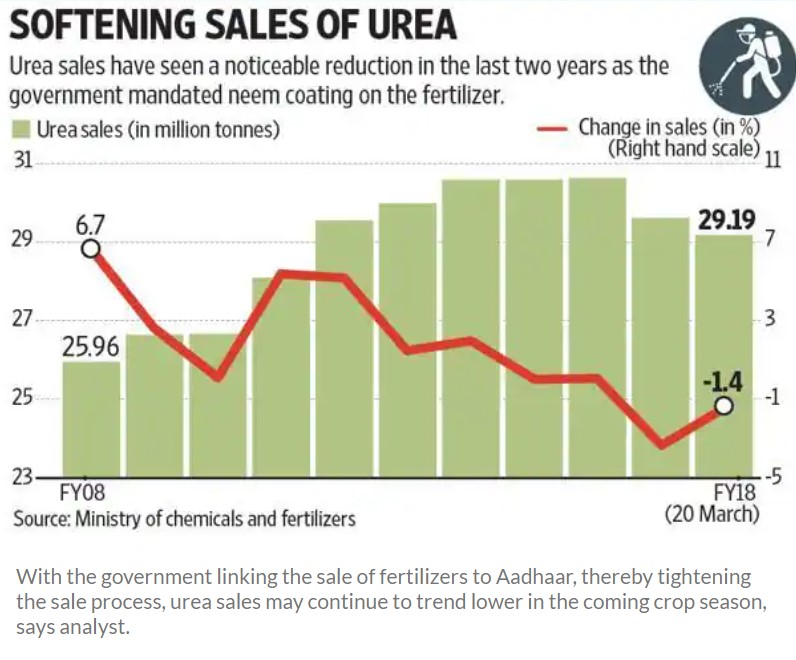

- To curb diversions, in 2015, the government mandated that all urea supplies be neem-coated, making them unsuitable for use in chemical industries and thus reducing the incentive for manufacturers/dealers to divert them.

- However, ensuring comprehensive neem-coating is challenging, as policing the vast quantities across the country is nearly impossible.

Link Fertilizer Purchases to the Size of a Farmer’s Landholding:

- To further prevent non-farmers from purchasing subsidized fertilizers, the government now plans to link fertilizer purchases to the size of a farmer’s landholding.

- The goal is to ensure that farmers only buy the amount needed for their crops and do not acquire excess fertilizer to sell at higher prices for industrial use.

- Farmers’ land and crop data will be stored on their biometric cards. When purchasing fertilizer, the retailer’s PoS machine will read the card and provide the number of bags corresponding to the data, not the quantity requested verbally by the farmer.

Challenges in Implementing these Ideas:

- The government needs comprehensive and accurate data on over 140 million farm households, including details on land holdings, crops grown, and soil nutrient status.

- Ensuring complete and accurate data coverage is crucial, as any errors could lead to either shortages or surpluses of fertilizer.

- Additionally, this data must be updated in real-time to reflect changes in weather and rainfall affecting fertilizer needs.

Conclusion:

Despite these efforts, the government may be overlooking a fundamental issue. The core problem behind the leakage is the artificially low MRP of urea. When urea is sold at one-tenth of its supply cost, it creates a strong incentive for misuse and diversion by unscrupulous players. Individuals will find ways to bypass regulations, leading to subsidy misuse. The solution is to end price controls on fertilizers and provide subsidies directly to farmers through the DBT system.

Driving Innovation: Role of Intellectual Property in India

Context:

In his 76th Independence Day speech on August 15, 2022, the Prime Minister emphasized the importance of innovation, particularly indigenous innovations, under the theme “Jai Anusandhan”. Innovation is crucial for India to become a self-reliant, competitive, and USD 30 trillion economy by 2047. It has the potential to significantly boost productivity, enabling the country to advance to higher value-added products and services across various sectors.

Relevance:

GS3-

- Indigenization of Technology

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs)

GS2- Government Policies & Interventions

Mains Question:

India can emulate Japan’s post-Meiji transformation by harnessing innovation, embracing change and cultivating a risk-taking culture. Analyse in the context of boosting innovation and research in India. (10 Marks, 150 Words).

Recent Developments:

- Recently, we have seen a global shift from a knowledge economy to an era dominated by artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual technologies.

- Additionally, the unprecedented scale of the pandemic underscored the need for an innovation ecosystem to develop new cures, including vaccines, medicines, and diagnostics.

- Despite India’s strong scientific and technical foundation, the private sector has historically made modest investments in research and development (R&D).

Approach Towards Innovation:

- India has adopted a unique approach to innovation to address its specific challenges. Transformational digital public infrastructure, such as the Aadhaar platform, exemplifies this approach.

- Another example lies in the biopharmaceutical sector, in which, given concerns about public health, medicine affordability, and protecting the domestic industry, India has focused on public-sector-led collaborative innovation, encouraging the private sector to invest in R&D in priority areas.

Private Sector’s Participation in Research and Development:

- Publicly supported research often drives initial discoveries, but the private sector is essential for developing new technologies and bringing them to market. Private sector innovation is crucial for India to remain competitive in a rapidly evolving global market.

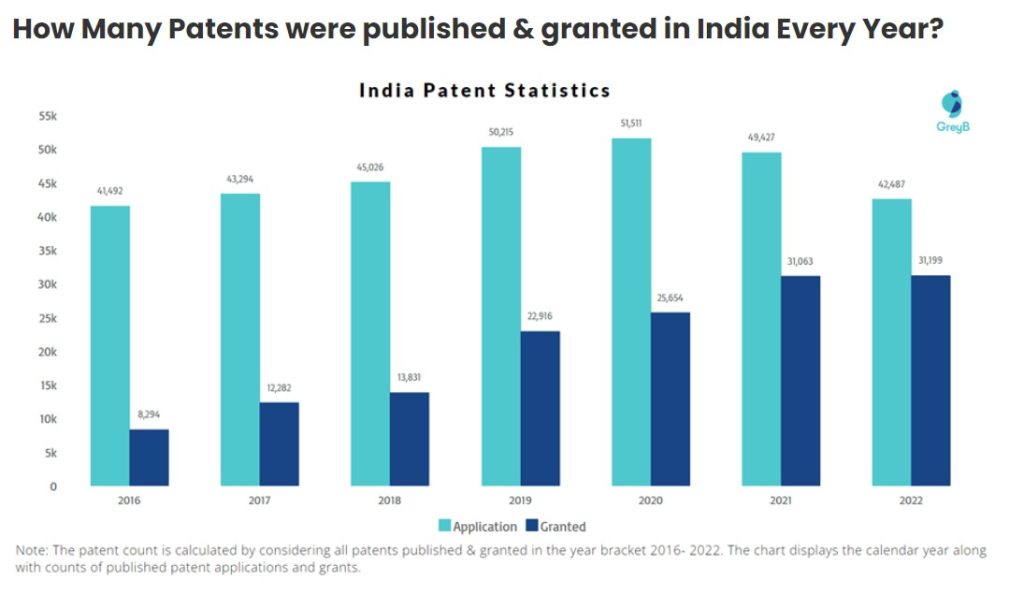

- Innovation can be measured by a company’s R&D expenditure as a percentage of its revenue. Additionally, a company’s innovation index can be assessed by the number of granted patents, patent applications, the extent of international filings, and the quality of the patents.

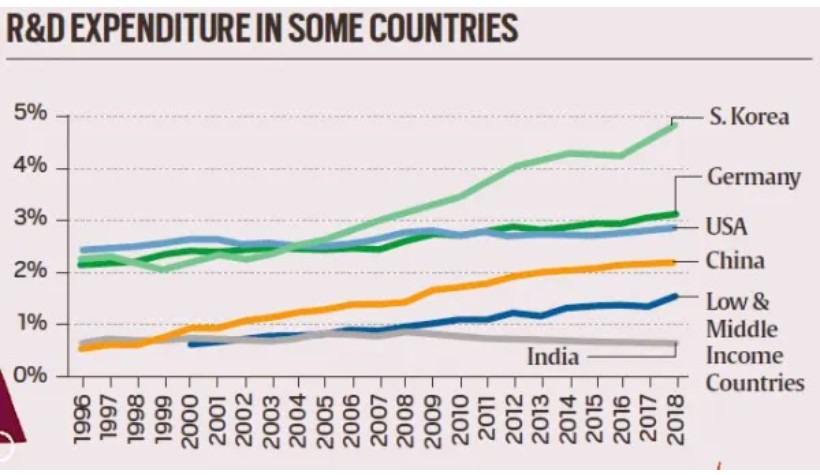

- The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Commerce’s 161st Report on the IPR Regime in India (July 2021) expressed concern over the slow increase in patent numbers in India compared to the US and China. This slow growth is linked to the low R&D spending, which is only 0.7 percent of India’s GDP.

- Globally, the companies with the highest R&D spending include major US tech firms like Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Intel Corp., as well as leading biopharmaceutical companies such as Roche, J&J, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck & Co.

- The list also features three Chinese companies—Huawei, Tencent Holdings, and Alibaba; South Korea’s Samsung; and European automobile manufacturers like Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz.

- In the biopharmaceutical sector, the removal of product patent protection for drugs in 1970 enabled reverse engineering, which led to the exponential growth of India’s domestic generic industry, earning the country the title of ‘the pharmacy of the world.’

- However, this lack of effective patent protection significantly hindered corporate investment in R&D and the discovery of new molecules. To date, Zydus Cadila’s Saroglitazar, launched in 2013, is the only entirely indigenously discovered compound.

Way Forward:

- India can ignite its innovative potential by leveraging its strengths, embracing change, and fostering a risk-taking culture.

- Japan’s transformation after the Meiji Restoration—from an importer and imitator of foreign technologies to a global innovation powerhouse that has shaped the world’s technological landscape—illustrates that necessity is the mother of invention.

- Creating an environment conducive to innovation is complex and multifaceted. In his book Red Teaming, Bryce Hoffman emphasizes that disruptive innovation demands critical and contrarian thinking.

- Therefore, it is crucial to shift our education system’s focus away from rote memorization and conformity to foster scientific temper, risk-taking, and entrepreneurial spirit.

- Additionally, fostering closer collaboration between academia and industry is essential for commercializing innovation.

- A notable example is Prof. Rahul Purwar from IIT Mumbai, who obtained marketing approval for India’s first indigenously developed cell and gene therapy for cancer treatment.

Conclusion:

A strong, meaningful, and predictable intellectual property rights system is vital. Such a system provides the economic incentives necessary for inventors and investors to commit risk capital to innovative activities, which are inherently high-risk endeavors.