CONTENTS

- Renew the Generalised System of Preferences

- Scheme for Care and Support to Victims under the POCSO Act, 2012

Renew the Generalised System of Preferences

Context:

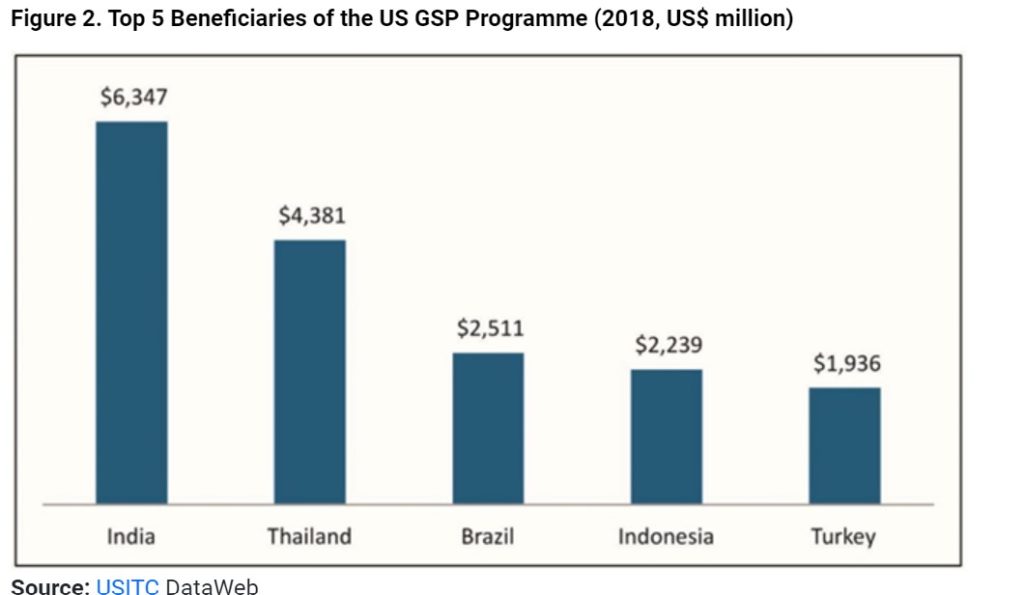

In the realm of obscure international trade terminology, the “generalised system of preferences” (GSP) stands out. GSP is a policy that most developed countries have employed for about fifty years, providing lower tariffs to encourage economic reforms in developing countries.

Relevance:

GS2-

- Groupings & Agreements Involving India and/or Affecting India’s Interests

- Effect of Policies & Politics of Countries on India’s Interests

Mains Question:

There needs to be higher ambition on trade in order to take the U.S.-India strategic relationship even further. Discuss in the context of US’s Generalised System of Preferences policy. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

More on the GSP:

- Each developed country has tailored its own GSP program with specific criteria for economic reform, ensuring these programs do not harm domestic production.

- Essentially, GSP is the oldest and most extensive “aid for trade” strategy in the modern multilateral trading system, as represented by the World Trade Organization.

- Unique to the U.S., the GSP program requires periodic reauthorization by Congress. This reauthorization is often challenging, especially in a polarized political climate.

- Currently, the U.S. GSP program, which expired in 2020, remains in a state of uncertainty despite assurances of bipartisan support.

- In the U.S., support for GSP is diverse. Last November, a bipartisan group of Florida House members wrote a letter advocating for urgent GSP renewal, emphasizing its role in reducing dependency on China and lowering tariffs for Florida’s consumers and manufacturers.

- In the current climate of friendshoring and nearshoring, GSP is a valuable tool for new supply chain strategies.

- Surprisingly, there is even strong bipartisan support for resuming GSP discussions with India.

Significance of GSP:

- GSP is crucial for providing stable market access to developing countries struggling to engage in global trade.

- It benefits small businesses and women-owned enterprises, empowering them beyond local markets.

- Recent analysis indicates that GSP is essential in offering alternatives to Chinese imports and giving an edge to suppliers from trusted developing markets.

- GSP criteria also promote labor reforms, environmental sustainability, and intellectual property rights protection.

- Additionally, GSP imports help lower tariff costs for American companies, many of which are small- and medium-sized enterprises.

U.S.-India Trade Relationship:

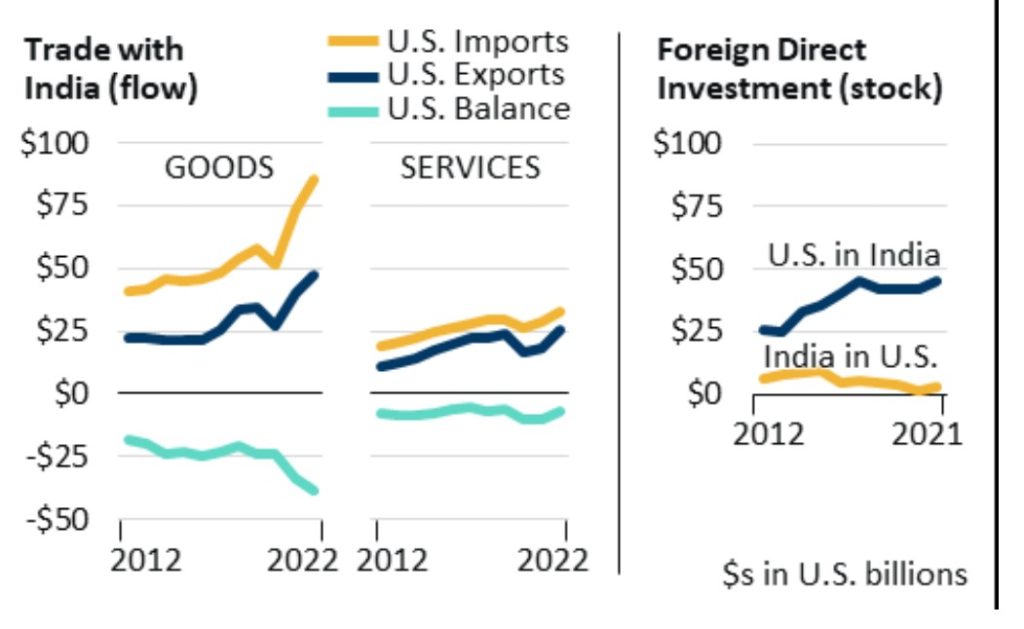

- While further arguments for renewing the GSP are unnecessary, the U.S.-India trade relationship could provide decisive support.

- Renewing GSP is widely believed to facilitate extensive U.S.-India trade negotiations, potentially elevating their bilateral trade well beyond the current $200 billion.

- Before the GSP program expired in 2020, negotiations between the U.S. Trade Representative and India’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry were close to finalizing a comprehensive deal.

- Projections at that time suggested that a historic bilateral trade agreement could encompass up to $10 billion in trade, including sectors such as medical devices, various agricultural commodities, corn-based ethanol for fuel, and IT products.

- Although the U.S. and India have made significant strides in their trade relationship, their tools for further enhancing trade are limited.

- Despite India’s active efforts to negotiate free trade agreements (FTAs) with partners like the European Union, the U.K., the European Free Trade Association, Australia, and the UAE, the Biden administration has stated that the U.S. will not pursue FTAs at this time.

- Existing trade dialogues between the U.S. and India lack the leverage needed for ambitious negotiations.

- Private sectors in both countries are collaborating to boost investments in critical and emerging technologies, from smartphone manufacturing to semiconductor production.

- However, they lack the regulatory stability and business ease that a robust, enforceable trade agreement could provide.

- This is where the GSP should be considered. Both sides would benefit significantly from negotiations on India’s GSP benefits once the U.S. Congress renews the program.

- Given the current U.S. policy against negotiating FTAs, no other trade tool or policy could be as effective with India as the GSP.

- Depending on the qualification criteria set by Congress in the final renewal legislation, a GSP negotiation could address trade in goods and services, protections for internationally recognized labor rights and restrictions on child labor, enforcement of environmental laws, and provisions on good regulatory practices and other factors relevant to business ease.

Conclusion:

As the U.S.-India strategic partnership strengthens and both countries play vital collaborative roles in the Indo-Pacific, they should aim higher in their trade relationship. While GSP alone cannot fully achieve this comprehensive goal, it would strongly signal their mutual commitment to this path.

Scheme for Care and Support to Victims under the POCSO Act, 2012

Context:

On November 30, 2023, the Ministry of Women and Child Development announced the “Scheme for Care and Support to Victims under Section 4 & 6 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012.” This scheme aims to provide comprehensive support and assistance to minor pregnant girl victims “under one roof,” ensuring immediate access to both emergency and non-emergency services for long-term rehabilitation. However, the scheme’s name does not clearly reflect its purpose.

Relevance:

GS2-

- Government Policies and Interventions for Development in various sectors and Issues arising out of their Design and Implementation

- Welfare Schemes for Vulnerable Sections of the population by the Centre and States and the Performance of these Schemes;

- Mechanisms, Laws, Institutions and Bodies constituted for the Protection and Betterment of these Vulnerable Sections

Mains Question:

Recently, the Ministry of Women and Child Development announced the “Scheme for Care and Support to Victims under Section 4 & 6 of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, 2012. In this context, analyse the objective of the scheme, the prominent gaps and loopholes in it and suggest a way forward strategy to deal with it. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Oversights and Inconsistencies:

Broader Scope:

- Initially, the scheme was intended only for abandoned or orphaned pregnant girls but has since been expanded to include all pregnant girl victims under the specified sections of the POCSO Act.

- Despite this expansion, the scheme has not been revised to reflect its broader scope adequately, leaving out necessary changes.

- The misleading title, whether accidental or deliberate, creates confusion in two ways.

- First, victims under Sections 4 and 6 of the POCSO Act can be of any gender.

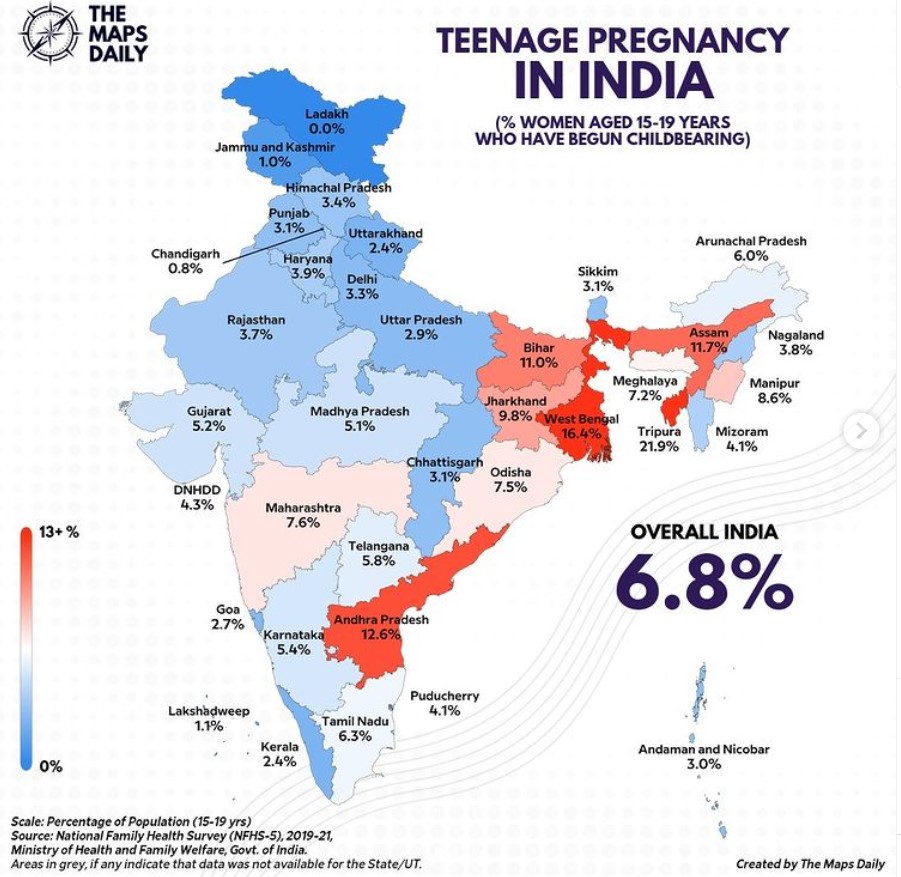

- Second, although the scheme targets all pregnant girls under 18, it implicitly acknowledges that many of these girls are between 13-18 years old and often become pregnant due to consensual, exploratory sexual activity, an established part of adolescent development.

Lack of Clarification in case of medical termination of pregnancy (MTP):

- While the scheme ostensibly aims to serve “every minor pregnant girl child victim,” it explicitly categorizes only those who choose to continue their pregnancies or those not allowed by the court to undergo a medical termination of pregnancy (MTP).

- The scheme does not clarify whether benefits will continue if the victim opts for an MTP or has a miscarriage.

- Similarly, it is unclear whether benefits extend to a girl who turns 18 after reporting the case and confirming the pregnancy, or if her circumstances change up to age 23, during which she can receive benefits from Mission Vatsalya (“a roadmap to achieve development and child protection priorities aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals”).

- It would be disappointing if this scheme, meant for a vulnerable group, ends up discriminating and short-changing them.

Inconsistencies with Existing Legislation:

- The scheme is plagued with significant oversights and inconsistencies with existing legislation, rules, orders, and guidelines.

- For instance, it incorrectly states that Section 27 of the POCSO Act, 2012, which pertains to the medical examination of a child, should guide the placement of minor pregnant girls in institutional or non-institutional care.

- It also wrongly implies that the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) can consent to the medical examination for sexual assault of any child under 12, regardless of whether her parents or guardians are present.

Contrary to the Rules:

- Victims under the POCSO Act, including pregnant victims, are not automatically classified as Children in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP).

- Benefits can be extended to them without this classification if their family or guardian can provide adequate care and protection.

- However, the scheme mandates that all pregnant girls must be classified as CNCP to receive benefits.

- This contradicts Rule 4(4) of the POCSO Rules and Section 2(14) of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (JJ Act), necessitating their unnecessary production before the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) and compliance with all related procedures.

Monetary Implications:

- Given India’s notably high rates of child marriages and teenage pregnancies, the financial burden on the government proposed by the scheme will be substantial.

- According to the scheme, each pregnant girl under 18 who meets the new criteria—every reported case under the POCSO Act, 2012—will receive an initial payment of ₹6,000 and a monthly payment of ₹4,000 as stipulated in Mission Vatsalya until the age of 21, with a possible extension to 23 years.

- An RTI reply indicated that 1,448 girls under 18 gave birth between January 2021 and October 2023 in a southern district.

- Using a hypothetical scenario where the average age of these young mothers at delivery is 16, and considering Mission Vatsalya support continues until age 23, the financial outlay per mother would be ₹6,000 (one-time payment) + ₹4,000 x 84 months = ₹3,42,000. For 1,448 girls and their babies, the total would be ₹49,52,16,000.

Conclusion:

To prevent the inevitable confusion if the scheme is implemented in its current form, it is crucial for the Ministry of Women and Child Development to revise it. The revision should align with the provisions of existing legislation, rules, guidelines, and protocols. Data that can substantiate many of the scheme’s aspects will be essential for this process. This also underscores the need for the government to enhance its efforts in establishing safeguarding systems for children and adolescents, promoting sexual and reproductive health related information, and ensuring abuse prevention education for the entire community.