CONTENTS

- The Tyranny of Inequality

- Protecting Indian Capital in Bangladesh

The Tyranny of Inequality

Context:

Honoré de Balzac, the French novelist, once wrote, “Behind every great fortune there is a crime.” However, this statement is only partially true, as it fails to acknowledge that the accumulation of income and wealth also fosters serious offenses and crimes.

Relevance:

GS3- Inclusive Growth

Mains Question:

Higher income inequality causes more widespread corruption, while greater confidence in the judiciary curbs it. Analyse. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Studies on Inequality:

- Based on an analysis of the Gallup World Poll (GWP) Survey for India (2019-23) and the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE)’s Consumer Pyramid Household Survey, we argue that income inequality fuels corruption, particularly at the intersection of government and business.

- For instance, the approval of contracts for major infrastructure projects like highways, bridges, and ports by public officials often benefits wealthy and influential private investors.

- Once individuals become rich, their desire for more wealth can override moral concerns, leading to corrupt practices. Wealth accumulation then becomes easier, facilitated by tactics like share market manipulation, political lobbying to secure contracts, and investments in offshore funds.

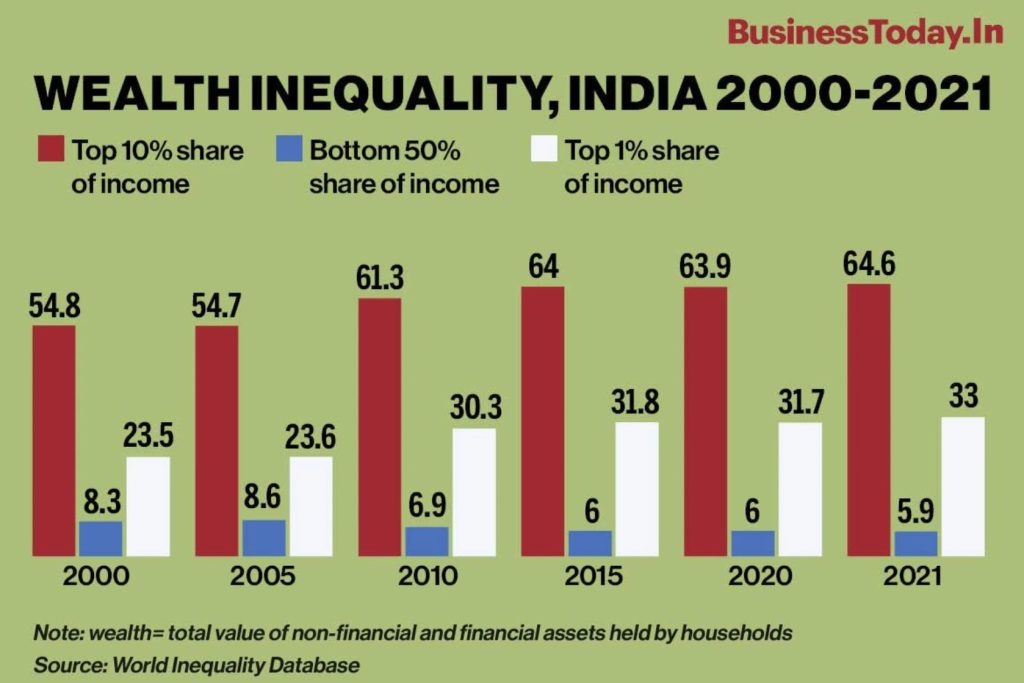

- In a recent study, Thomas Piketty and his colleagues highlighted the staggering rise in wealth and income inequality in India over the past few decades, particularly between 2014 and 2022.

- Today, the top 1% of the population controls more than 40% of total wealth in India, up from 12.5% in 1980.

- The top 1% of income earners now receive 22.6% of total pre-tax income, compared to 7.3% in 1980.

- As a result, India has become one of the most unequal countries in the world, yet recent studies have largely overlooked the harmful effects of this growing economic inequality.

Methodology:

- Our goal is to examine the connection between income inequality and corruption, with a specific focus on whether increased income inequality fueled corruption between the government and businesses during the 2014-22 period.

- Due to the lack of comparability between the two recent National Sample Survey (NSS) rounds on household expenditure for 2018 and 2022 with the NSS round for 2012, we rely on data from the Gallup World Poll (GWP) and the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) as alternatives.

- While the GWP has a small sample size, which limits its representativeness for a country as vast and diverse as India, it offers valuable data on variables like corruption, which are difficult to measure.

- We have used the Piketty measure of income inequality, defined as the ratio of the share of total income held by the top 1% to that of the bottom 50% of the population.

- Although inequality in the distribution of consumption expenditure is typically lower than that of income distribution, we have chosen to focus on consumption expenditure due to its greater reliability.

- Corruption is generally understood as the misuse of public office for private gain, which excludes corruption within businesses (such as insider trading).

- Therefore, a broader and more comprehensive definition considers the misuse of public resources by executives in both the public and private sectors for private gain, while also acknowledging the role of politicians.

- The GWP includes a question on whether corruption is perceived to be widespread, with a “yes” response scored as 1.

- By aggregating these responses, we obtain a measure of corruption based on individual perceptions.

- Corruption can manifest in three areas: within the government, within businesses, and at the intersection of government and businesses.

- Our focus is on the relationship between inequality and corruption at this intersection—for instance, whether government contracts for building ports are influenced by bribes from wealthy investors.

- Corruption has increased following globalization, as natural resources have become more valuable, and regulatory agencies responsible for allocating these resources have grown more compliant with powerful business interests and corrupt public officials.

- Moreover, the ‘Make in India‘ initiative has not yet achieved significant success, as macroeconomic indicators such as manufacturing, FDI, exports, and employment have not shown improvement.

- Even worse, as highlighted in a 2023 Carnegie India essay, increases in import tariffs and tax cuts have been distortionary.

Findings:

- This situation suggests a higher likelihood of rent-seeking by wealthy and influential investors. Rent-seeking refers to the use of resources to obtain unwarranted financial gain from external entities, such as government or public agencies, without providing anything of value in return to them or society.

- Economic rents lead to resource dissipation, which can be more damaging than the waste associated with the rent itself.

- Groups competing for these rents invest time and money in wealth transfer rather than wealth creation.

- Given that corruption at the intersection of government and business remained high between 2014 and 2022, it is likely that rent-seeking also persisted at elevated levels.

- Without delving into the specifics of the allegations by Hindenburg regarding the involvement of the SEBI chair and her husband with the Adani Group’s offshore fund, and the subsequent slowing of the SEBI probe, this may be indicative of a larger and growing problem.

- Our analysis shows that income inequality has been largely driven by speculative investments, such as mutual funds, while savings in fixed deposits and post offices have helped curb it.

- Trust in the judiciary is influenced by the conviction rate, but it increases at a diminishing rate.

- We find that higher income inequality leads to widespread corruption, whereas greater confidence in the judiciary helps reduce it.

Conclusion:

While the recent Budget missed the opportunity to impose higher taxes on the wealthy, achieving greater transparency and accountability in regulatory agencies remains elusive. A more competitive political system and private business sector pose significant challenges, but their potential to create a more prosperous India is undeniable.

Protecting Indian Capital in Bangladesh

Context:

The recent dramatic events in Bangladesh, which led to the resignation and departure of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, have created a political vacuum and introduced uncertainty in India’s eastern neighbor. Beyond the political and diplomatic implications of this crisis for India, a significant concern is how it will affect Indian companies operating in Bangladesh.

Relevance:

GS2-

- India and its Neighbourhood- Relations

- Effect of Policies and Politics of Developed and Developing Countries on India’s interests

- Indian Diaspora

Mains Question:

Examine the consequence that recent incidents in Bangladesh can have on Indian investments in the country. What can be done to minimise the impact of this crisis on the Indian capital? (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Indian Investments in Bangladesh:

- Indian firms have invested in various sectors in Bangladesh, including edible oil, power, infrastructure, fast-moving consumer goods, automobiles, and pharmaceuticals.

- Despite political opposition, the Sheikh Hasina government welcomed Indian investors, implementing measures such as the establishment of designated special economic zones to attract them.

- However, her opponents, displeased with India’s perceived support of Hasina’s regime, initiated an “India Out” boycott movement targeting Indian products.

- Now that Ms. Hasina is no longer in power, the interim or new government might adopt a hostile stance toward Indian companies, potentially altering existing laws or introducing new regulations that could negatively impact Indian investments.

What Strategies can Indian Businesses Pursue in such a Scenario?

Legal Protection for Indian Investors:

- Jeswald Salacuse outlines three primary legal frameworks that generally govern foreign investment.

- First, the domestic laws of the country where the investment is made.

- Second, contracts between the foreign investor and the host state’s government or between foreign investors and companies within the host state.

- Third, international law, which includes applicable treaties, customs, and general legal principles that have gained recognition as international law.

- Indian companies with investments in Bangladesh can rely on the first two legal frameworks to safeguard their investments against regulatory risks. For example, they can invoke Bangladesh’s Foreign Private Investment (Promotion and Protection) Act.

- However, relying on the host state’s domestic law has its limitations, as the state can unilaterally change these laws to the detriment of the investor at any time.

- Similarly, contracts may offer limited protection when challenging sovereign actions by the state that adversely affect foreign investments.

- Consequently, the third legal framework, international law, becomes particularly important in such situations.

The India-Bangladesh BIT:

- International law cannot be unilaterally altered and serves as a mechanism to hold states accountable for their sovereign actions.

- In the realm of foreign investment protection, the most critical tool in international law is the bilateral investment treaty (BIT).

- A BIT is an agreement between two countries designed to safeguard investments made by investors from both nations.

- These treaties protect investments by setting conditions on the regulatory actions of the host state, thus preventing undue interference with the rights of foreign investors.

- Key provisions in BITs include restrictions on unlawful expropriation, obligations for the host state to provide fair and equitable treatment (FET) to foreign investments, and non-discrimination against foreign investors.

- BITs also grant foreign investors the right to directly sue the host state before an international tribunal if they believe the host state has violated its treaty obligations, a process known as investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).

- According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), by the end of 2023, 1,332 known ISDS claims had been brought.

- In the event of adverse regulatory actions by the Bangladeshi government, Indian companies can rely on the India-Bangladesh BIT, which was signed in 2009.

- Although India has unilaterally terminated most of its BITs, the one with Bangladesh remains in effect.

- This treaty includes comprehensive investment protection measures, such as an unqualified FET provision, which could be beneficial for Indian companies challenging Bangladesh’s sovereign regulatory actions.

The Complication- Joint Interpretative Notes (JIN):

- However, there is a complication: the Joint Interpretative Notes (JIN) that India and Bangladesh adopted in 2017 to clarify the meaning of various terms in the 2009 treaty.

- This JIN, now part of the BIT, was introduced at India’s insistence as part of its broader effort to revise its investment treaty practices to protect its regulatory authority.

- India proposed similar JINs to several other countries, without fully considering whether it had a defensive or offensive interest in relation to each specific country. The JIN has diluted the investment protection features of the BIT.

- For example, taxation measures are excluded from the treaty’s scope. Similarly, the FET provision is tied to customary international law, which imposes a higher standard for proving a treaty violation.

- The JIN was crafted from the perspective of a capital-importing country to protect its regulatory actions from ISDS claims.

- In the case of India and Bangladesh, however, India is the capital exporter and Bangladesh the importer.

- Ironically, the JIN that India developed could end up benefiting Bangladesh rather than the Indian companies operating there.

Conclusion:

While Bangladesh is the immediate focus, the issue extends beyond India’s eastern neighbor. India’s outbound investments have significantly increased, with outward foreign direct investment reaching approximately $13.5 billion in 2023, according to UNCTAD. India is now among the top 20 capital-exporting countries. This growth underscores the importance of legal protection for Indian companies operating abroad. Consequently, India needs to develop its investment treaty practices by considering both its role as a host and as a home country, rather than focusing solely on the former.