CONTENTS

- The Essence of India’s Inflation Problem

- Ensuring Social Justice in the Bureaucracy

The Essence of India’s Inflation Problem

Context:

The Economic Survey presented before this year’s Union Budget makes a significant suggestion with implications for inflation control. It proposes removing food prices from the inflation target that the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is responsible for managing. In technical terms, this would mean shifting the focus from ‘headline’ inflation to ‘core’ inflation. Understanding the potential impact of such a change requires considering two key aspects: India’s recent experience with inflation and the current inflation control policy.

Relevance:

GS3-

- Fiscal Policy

- Monetary Policy

- Food Processing

- Growth and Development

- Mobilization of Resources

Mains Question:

Recently, food price inflation in India has been unusually high. What are the possible reasons behind this occurrence and what can be done to target it? (10 Marks, 150 Words).

Food Prices and Inflation Trends:

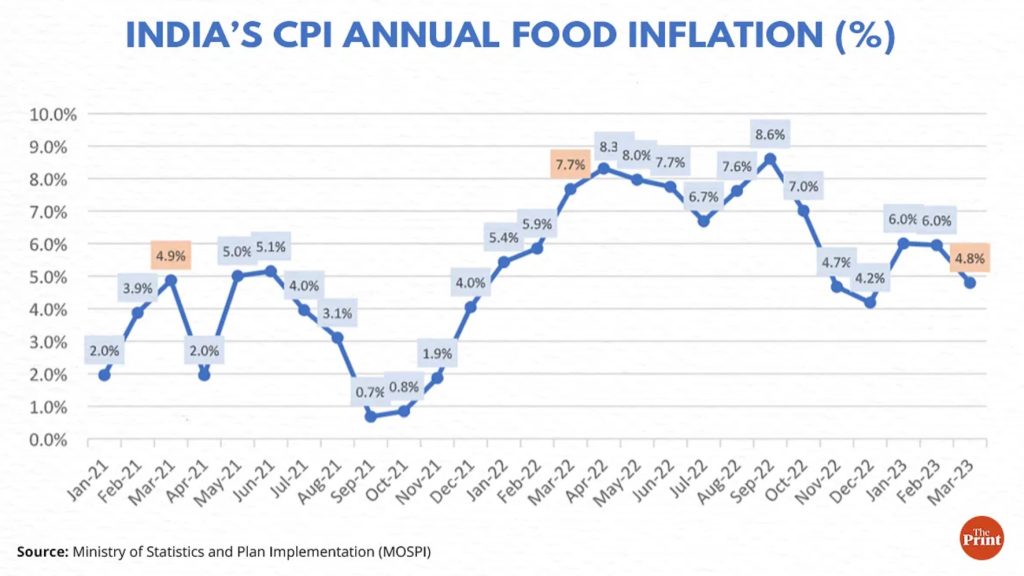

- With food inflation high and food making up a significant portion of the consumer price index, overall inflation has also been elevated.

- The second aspect involves the current inflation control strategy. Since 2016, the RBI has been tasked with controlling inflation through interest rate adjustments, a practice known as ‘inflation targeting.’

- This approach implies a certain level of precision in managing inflation, but the RBI has missed its 4% target every year for the past five years.

- Similar challenges have been observed in the UK and the US, where central banks have also struggled to meet inflation targets, largely due to global food price fluctuations.

Questions Raised by the Economic Survey:

- The Economic Survey’s suggestion raises two important questions: Is excluding food prices from the inflation target justifiable in terms of economic policy goals?

- And, would the RBI be more successful in controlling core inflation than it has been with headline inflation? The answer to both is likely ‘no.’

- In India, food accounts for nearly 50% of household expenditure, a very high proportion compared to international standards (e.g., less than 10% in the US).

- This high share makes Indian households highly sensitive to food price increases, and ignoring food prices in inflation targeting would neglect what matters most to a large segment of the population.

- In June, the year-on-year rise in food prices was nearly 10%, and this trend has been persistent since 2019, even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the Ukraine war, suggesting domestic factors are at play.

- The argument that food price fluctuations are ‘transitory’ is not convincing in the Indian context, where food price inflation has remained consistently positive for over a decade.

- The idea that these fluctuations are merely temporary does not hold up to scrutiny.

Targeting Core Inflation:

- This brings us to the second issue—whether the RBI would be more successful if it focused solely on targeting core inflation. The answer is fairly straightforward.

- Over the past 13 years, the annual average core inflation has met the targeted 4% in only one year, and even then, just barely. This outcome isn’t surprising, as our statistical analysis reveals two reasons why this is the case.

- First, an increase in the RBI’s repo rate doesn’t necessarily dampen core inflation as expected. In fact, raising the rate can actually lead to higher inflation.

- The economic reasoning behind this is sound: as higher interest rates suppress demand, firms may increase prices to protect their profits.

- This is especially true when firms face the double challenge of rising working capital costs and declining revenues due to reduced output.

- Additionally, our analysis shows that food price inflation influences core inflation, which makes sense.

- Since food prices impact wages—a significant component of a firm’s costs, along with materials—rising food prices push wages higher, contributing to core inflation.

- The finding that food prices affect core inflation undermines the effectiveness of targeting core inflation.

- It also offers a deeper insight: since labor is involved in all forms of production to varying degrees, changes in food prices drive inflation across the entire economy.

- Monetary policy, which operates through interest rate changes, is ineffective in controlling inflation because the central bank has no influence over food prices.

- Given that these points are well understood among informed economists, one might wonder why India’s economic policy continues to rely on the idea that inflation control should be left to the central bank.

- The answer lies in an ideological shift that occurred globally after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

- The prevailing view became that production should be left to the market, while inflation control should be the sole responsibility of the central bank.

- Since 1991, all political parties in India have been eager to align with Western practices, regardless of whether they are irrelevant or even harmful to the country. Excluding food price inflation from the inflation target is one such misguided practice.

Focus on Agricultural Production:

- The escalating price of food is central to India’s inflation issue. Simply removing food prices from the official inflation measure does not address the ongoing problem.

- As discussed, if food prices continue to rise as they have over the past five years, the RBI will struggle to control core inflation as well.

- The current inflation in India can only be effectively managed through supply-side measures aimed at increasing agricultural yields.

- While the challenges are significant, they are not insurmountable for a country that overcame chronic food shortages more than 50 years ago.

- Success would require a comprehensive approach to agricultural production that keeps costs in check, ensuring a steady supply at stable prices as the population and economy grow.

- Excluding food inflation from the inflation target without any strategy for controlling it would leave India vulnerable to a persistent threat to its population’s standard of living.

Conclusion:

The Economic Survey suggests that the negative impact of food price inflation could be mitigated by income transfers to households. However, if food prices continue to rise faster than overall inflation, as they are now, such transfers would consume an increasing share of the Budget, leaving less funding for public goods. This is undesirable. There is no alternative to controlling the rise in prices across all goods, which remains the stated policy.

Ensuring Social Justice in the Bureaucracy

Context:

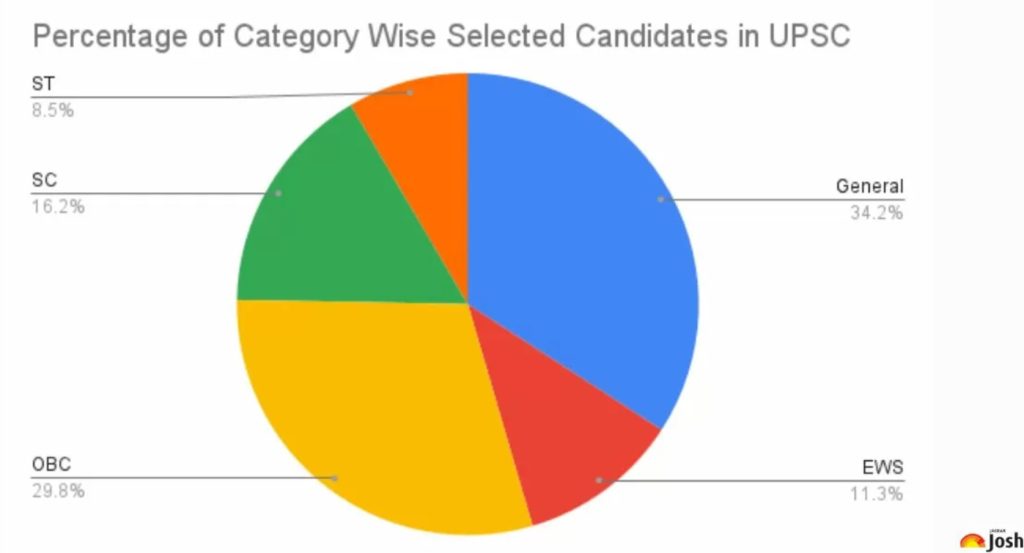

During his parliamentary address on July 29, 2024, Leader of the Opposition expressed concern over the absence of Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) officers among the 20 individuals involved in drafting the 2024 Budget proposals. He pointed out that only one officer from the minority communities and another from the Other Backward Classes (OBC) category participated in the process.

Relevance:

- GS2- Aptitude and Foundational Values for Civil Service

- GS3- Inclusive Growth

- GS4- Aptitude and Foundational Values for Civil Service

Mains Question:

Is there a significant underrepresentation of officers from reserved categories at the policy-making level in the government? What can be done to develop a more inclusive civil service framework? (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Underlying Intention:

- The underlying intention was to emphasize that individuals from historically poor and marginalized sections of society are not represented in shaping a crucial aspect of the government’s economic policy.

- In response, the Union Finance Minister addressed the criticism by highlighting the lack of representation from these traditionally deprived groups in the charitable trust and foundation run by the Leader of the Opposition.

- What could have been a serious discussion was reduced to political point-scoring.

Upper Caste Domination Persists:

- These political exchanges overlooked the real reason behind the absence of SC/ST officers in the Budget-making process: the continued dominance of upper castes in senior levels of the civil service.

- This issue was evident in a response by Minister of State Jitendra Singh to a parliamentary question on December 15, 2022.

- In a report published the next day, this daily quoted Mr. Singh as stating, “Out of a total of 322 officers currently holding the posts of Joint Secretaries and Secretaries under the Central Staffing Scheme in different Ministries/Departments, 16, 13, 39, and 254 belong to the SC, ST, Other Backward Classes (OBC), and General categories, respectively.”

- Mr. Singh further clarified that the representation of Secretary and Joint Secretary-level officers stood at 4% and 4.9%, respectively.

- Clearly, there is a significant underrepresentation of officers from reserved categories at the policy-making level in the government.

- To increase the representation of SC and ST officers in the highest positions within the government, a fundamental shift from the traditional retirement age concept is required.

Eligibility and Age Factor:

- Currently, general category candidates between the ages of 21 and 32 are eligible to appear for the civil services examination, with a maximum of six attempts allowed.

- SC/ST candidates can take the examination until the age of 37, with no limit on the number of attempts.

- For OBC candidates, the upper age limit is 35 years, and they are allowed nine attempts.

- Persons with Benchmark Disabilities (PwBD) have an upper age limit of 42 years, with unlimited attempts if they belong to SC/ST and nine attempts if they are from other categories.

- As a result, SC/ST and PwBD candidates, regardless of their performance as civil servants, often do not reach the highest positions because they generally join the service later and retire before reaching the top.

- They typically retire at lower or middle levels, which is a clear implication of Jitendra Singh’s response.

- The civil service operates like a race where those who join at a younger age have a better chance of reaching the top, even if their performance isn’t as strong as those who join later. This is primarily due to the age factor.

- Logically, the government’s focus should be on an official’s efficiency and competence, rather than the age at which they entered the civil service within the prescribed limits.

- If this approach is accepted, it suggests that the current retirement pattern should be replaced with a fixed tenure for every civil service entrant, regardless of their age at entry, as long as it is within the prescribed limits. A possible fixed tenure could be 35 years.

- If there are concerns about individuals working into their seventies, the current age limits could be lowered to ensure that all candidates retire by around 67 years of age.

- As life expectancy in India is increasing, annual medical fitness examinations could be implemented after the age of 62.

- This age is mentioned because even today, some officers’ tenures extend to this age. Indeed, some individuals currently holding responsible positions, after retiring from government service, are well into their seventies.

Conclusion:

Prescribing a fixed tenure for all officers, regardless of their age of entry, would allow more SC/ST and OBC officers to reach the highest positions in government. This change would help realize the vision of a “Viksit Bharat” (Developed India) with social justice for all. As a first step, the formation of an independent, multi-disciplinary committee with sufficient representation from SC/ST, OBC, and PwBD groups should be considered with an open mind.