CONTENTS

- Share of Religious Minorities: A Cross-Country Analysis (1950-2015)

- Clearing the Confusion over ‘Saptapadi’

Share of Religious Minorities: a Cross-Country Analysis (1950-2015)

Context:

A recent “working paper” titled “Share of Religious Minorities: a Cross-Country Analysis (1950-2015),” authored by Shamika Ravi, an esteemed economist and member of the Economic Advisory Council (EAC) to the Prime Minister, alongside two co-authors, has ignited a political uproar. This paper delves into concerns about the dwindling proportion of Hindus in India’s population.

Relevance:

GS2- Diversity of India, Population and Associated Issues

Mains Question:

Linking demographic shifts directly to state actions is problematic. Analyse in the context of the recently released Share of Religious Minorities: a Cross-Country Analysis (1950-2015) working paper. (10 Marks, 150 Words).

About the Working Paper:

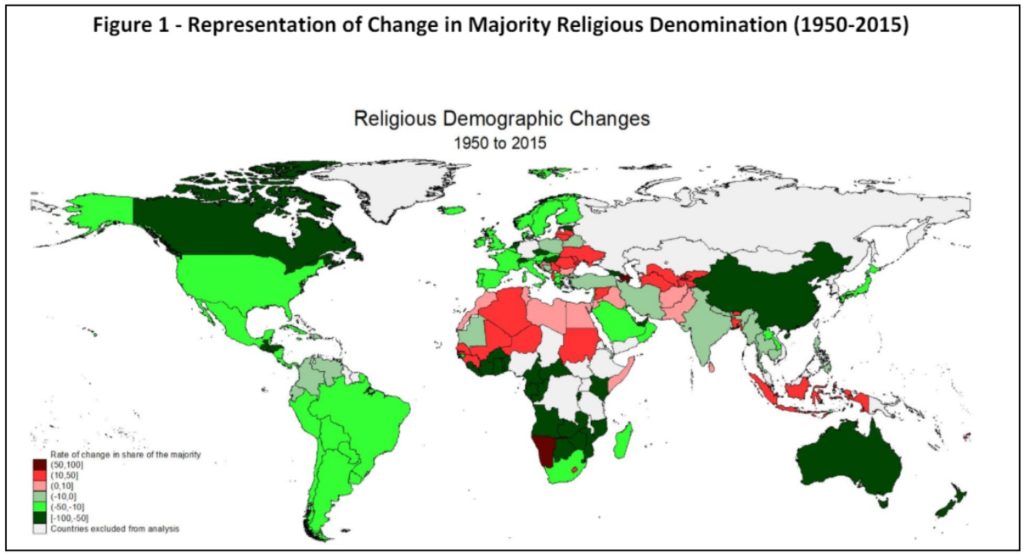

- The Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council (PM-EAC) report, titled “Share of Religious Minorities: A Cross-Country Analysis,” examined data regarding the religious makeup of populations across 167 countries spanning the period from 1950 to 2015.

- The study focused solely on countries where a particular religion constituted a majority (comprising more than 50% of the total population) in 1950.

- To analyze demographic shifts among religious minorities over the past 65 years, the study adhered strictly to the definition of majority (and consequently minority) as it stood in 1950. Countries lacking a clearly defined majority religion in 1950, as per the dataset, were omitted from the analysis.

- The research drew upon the Religious Characteristics of States Dataset 2017 to track religious demographics worldwide.

- This study serves as a descriptive examination of the status of religious minorities, gauged through changes in their proportion relative to the overall population of each country.

- This approach is deemed a reliable indicator, as alterations in minority population shares often stem from governmental policies, including the delineation of minority groups, a practice that is relatively uncommon on a global scale.

More on the Paper:

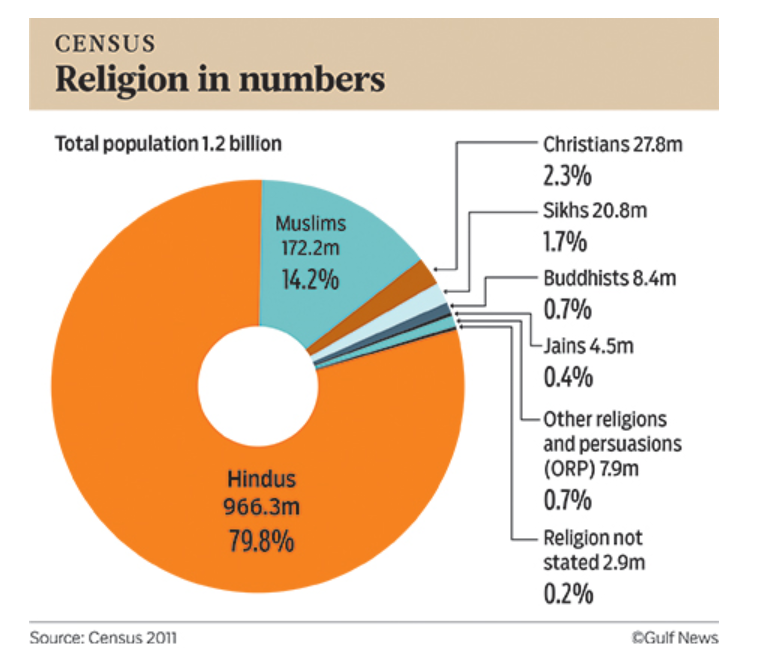

- The paper primarily presents and elucidates the dataset, emphasizing a well-known trend in India since 2011 and extensively discussed in recent years: the decline in the share of Hindus from 84.68% to 78% between 1950 and 2015, juxtaposed with a rise in the Muslim population from 9.84% to 14%.

- The authors underscore that this shift mirrors broader global trends, with most countries witnessing declines in adherents to their majority religions. They clarify that they do not establish causal links between specific state actions and demographic shifts.

- However, they observe that within the immediate South Asian region, India’s 7% relative decline in the Hindu population is notable, second only to Myanmar’s 10% decline among the majority Theravada Buddhists.

- From this point, the authors make an unsubstantiated deduction without conducting analysis or presenting additional data.

- They suggest that the increase in the Muslim population disproves media and UN human rights reports (which they reference) alleging discrimination and violence against Muslims in India.

- They specifically highlight Pakistan and Bangladesh to emphasize how “demographic shocks” have reduced the proportion of Hindus, the largest minority groups, in those countries.

- In doing so, the authors depart from their previous approach of avoiding causal explanations for demographic changes by attributing the growth in India’s Muslim population to “progressive policies and inclusive institutions.”

- This deviation prompts the question of whether India’s Parsi and Jain populations (whose declining numbers are mentioned) are experiencing similar declines due to unfavorable state policies.

Conclusion:

Considering that mundane factors such as decreasing fertility rates across religions and economic migration can account for some of these observed trends in India, it’s puzzling why the EAC would endorse a work that is, at best, incomplete and, at worst, misleading.

Clearing the Confusion over ‘Saptapadi’

Context:

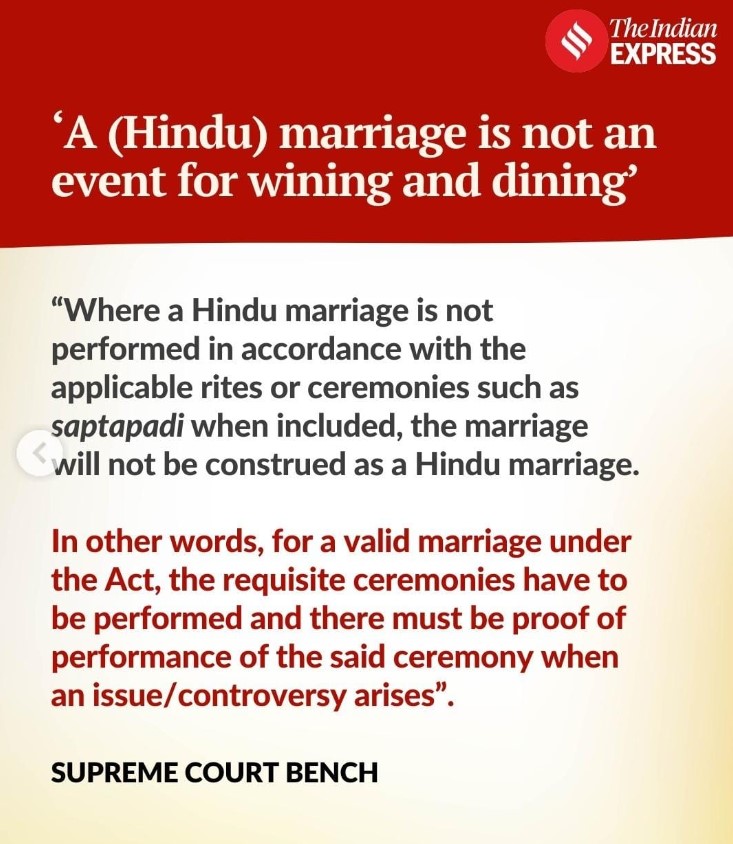

There appears to be a misunderstanding regarding the recent Supreme Court judgment in the case of Dolly Rani v Manish Kumar Chanchal, suggesting that a Hindu marriage between two individuals cannot be considered valid if the saptapadi ceremony is not performed. While the Court did not explicitly state this as law, it also did not specify in the judgment that there could be alternative ceremonies to validate the marriage.

Relevance:

- GS1- Indian Society

- GS2- Government Policies and Interventions

Mains Question:

A recent Supreme Court judgment on the decree of jactitation of marriage only reiterated what a plain reading of a Section of the Hindu Marriage Act tells us. Analyse. Also highlight other relevant rulings in this regard. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Background of the Case:

- The case in question involved a transfer petition filed by the petitioner-wife, seeking to transfer a divorce petition filed by the respondent-husband from Muzaffarpur, Bihar, to Ranchi, Jharkhand.

- During the pendency of this petition, both parties jointly applied under Section 142 of the Constitution for a declaration of invalidity of their marriage.

- They stated in their plea that they were engaged to be married on March 7, 2021, and “due to certain exigencies and pressures, they were constrained to obtain a marriage certificate dated July 7, 2021, from Vadik Jankalyan Samiti (Regd).”

- Using this certificate, they sought registration under the Uttar Pradesh Registration Rules, 2017, and were issued a ‘Certificate of Registration of Marriage.’

- Although the families of the parties set a date for performing the ceremony according to Hindu rites and customs, differences arose between them, leading to the husband filing for divorce while they were living separately.

- As there was no Hindu marriage between them, the issuance of a marriage certificate held no significance. They expressed the desire for the court to declare that no marriage occurred between them and allow them to pursue separate lives.

Analysing the Relevant Legislation:

- This common legal recourse, known as a decree of jactitation of marriage, is available for reasons other than the dissolution of a marriage deemed void or voidable under the Hindu Marriage Act.

- According to Section 7(1) of the Hindu Marriage Act, the only requirement for a Hindu marriage is that it be solemnized in accordance with the customary rites and ceremonies of either party.

- Saptapadi, involving the taking of seven steps by the bridegroom and bride jointly before the sacred fire, is a custom observed by certain Hindu communities but is not universally practiced among all denominations.

- The latter part of Section 7(2) states, “Where such rites and ceremonies include the Saptapadi… the marriage becomes complete and binding when the seventh step is taken.”

- However, this does not imply that saptapadi is the sole form of marriage solemnization. The Court simply reiterated the straightforward interpretation of the Section, which indicates that the necessary ceremonies for Hindu marriage solemnization must align with applicable customs or practices, and if saptapadi is performed, the marriage becomes legally binding upon completion of the seventh step.

- The legal principles elucidated in this case were not groundbreaking. The Hindu Marriage Act does not recognize marriage solely through registration. In many states, registration is now obligatory and typically follows a marriage ceremony.

Amendment Introduced by Tamil Nadu:

- In 1967, Tamil Nadu introduced an amendment simplifying marriage procedures. Upholding the validity of this amendment, a Division Bench of the Madras High Court, in S. Nagalingam v. Sivagami (2001), emphasized that the presence of a priest is not essential for a valid marriage.

- Parties can enter into matrimony in the presence of relatives, friends, or others, declaring their commitment to each other in a language understood by both, followed by a ceremony such as exchanging garlands, rings, or tying a thali. Any of these actions suffices to constitute a valid marriage.

- In the case of Ilavarasan v. The Superintendent of Police and Others (2023), the Court endorsed the aforementioned decision. It disagreed with a previous High Court ruling in Balakrishnan v. The Inspector of Police (2014), which deemed a suya mariyadhai form of marriage conducted in secrecy invalid.

- The Court criticized the assumption underlying the earlier decision that every marriage necessitates a public solemnization or declaration, noting that such a requirement could endanger the lives or integrity of the individuals involved, particularly in cases of familial or societal pressures.

- The Court argued that imposing a condition of public declaration, absent in Section 7A(1) of the statute, would unduly restrict the statute’s broad scope and infringe upon the rights protected under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- In the Ilavarasan case, the marriage was solemnized by a few lawyers in one of their chambers. While the Court acknowledged that a chamber cannot serve as a matrimonial venue, it recognized the role of the lawyers as witnesses if they acted in the capacity of friends or relatives.

Conclusion:

Concerns raised include the judgement did not delving into certain customary practices where elaborate ceremonies are not conducted beyond the exchange of garlands. Additionally, the judgment did not address the amendment to the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, in Tamil Nadu, which introduced the suya mariyadhai (self-respect) form of marriage through Section 7(a).