CONTENTS

- Addressing Retail Inflation

- No Population Census — in the Dark Without Vital Data

Addressing Retail Inflation

Context:

The RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) has decided for the ninth consecutive meeting to maintain the benchmark interest rates, as it continues to address retail inflation that has remained above the medium-term target of 4% for 57 months, eroding consumer confidence.

Relevance:

GS3-

- Fiscal Policy

- Inclusive Growth

- Public Distribution System (PDS)

Mains Question:

What are the factors contributing to India’s elevated food inflation despite falling overall inflation? What can be done to effectively manage the rising food prices? (15 Marks, 250 Words).

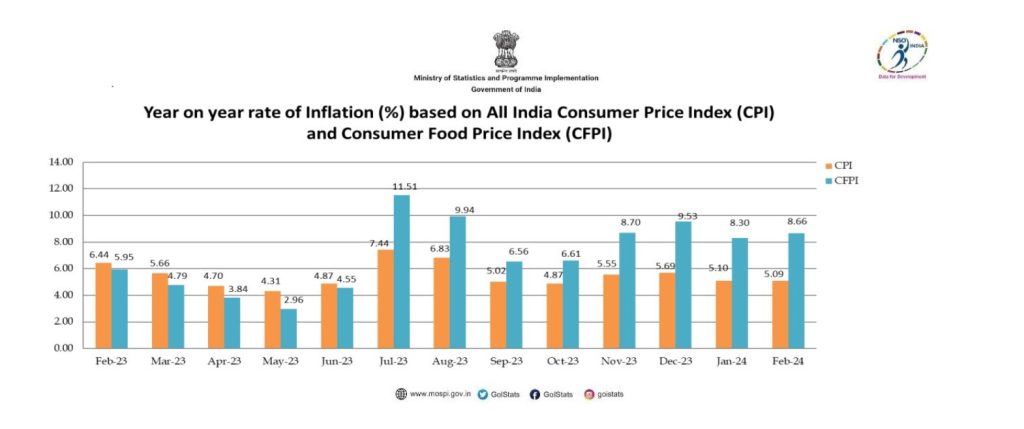

Consumer Food Price Inflation (CFPI):

- CFPI is a part of the larger Consumer Price Index (CPI), which the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) uses through the CPI-Combined (CPI-C).

- It tracks the price changes of a specific set of food items commonly consumed by households, such as cereals, vegetables, fruits, dairy products, meat, and other essential staples.

Elevated Food Prices:

- RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das emphasized that complacency is not an option, given the persistent risks posed by elevated food prices to households’ inflation expectations and the credibility of broader monetary policy.

- He pointed out that high food prices not only slowed disinflation during the April-June quarter but also maintained their momentum into July, with key vegetable prices showing significant month-on-month increases according to high-frequency food price data.

- Specifically, Department of Consumer Affairs data indicated that tomato prices surged by 62% sequentially, onions became almost 23% more expensive than in June, and potato prices rose by 18%.

- With food prices accounting for about 46% of the overall Consumer Price Index, they cannot be ignored—not only for their impact on headline inflation but more importantly because consumers are most affected by the influence of food prices on their monthly household budgets.

- While not directly mentioned, he suggested that the proposal in the Economic Survey to consider removing food prices from the inflation-targeting framework is not a practical solution given the current circumstances.

Factors Contributing to India’s Elevated Food Inflation Despite Falling Overall Inflation:

- Temperature and Weather Challenges: Adverse weather conditions, such as the prediction of a weak monsoon and heatwaves, have negatively impacted crop yields, especially for water-intensive crops like cereals, pulses, and sugar. This has led to supply shortages and higher domestic prices.

- Fuel Prices: The rising cost of fuel, which is a crucial input in agriculture, has significantly contributed to food inflation.

- Supply Chain Disruptions: Disruptions in the supply chain, caused by transportation constraints, labor shortages, and logistical challenges, have decreased the availability of food products, driving up prices.

- Global Impact: Although global food prices have decreased, India’s food prices remain high due to the limited transmission of international prices to domestic markets. The Russia-Ukraine war has further exacerbated this issue. While India is largely self-sufficient or an exporter for most agricultural commodities like cereals, sugar, dairy, fruits, and vegetables, it relies heavily on imports for edible oils (60% of consumption) and pulses, making these items more susceptible to global price fluctuations.

Decisions Made:

- The MPC, with a 4-2 majority vote, decided to maintain interest rates and keep its policy stance focused on withdrawing accommodation to ensure inflation aligns with the target.

- The committee also raised its projection for headline retail inflation in the July-September quarter to 4.4%, which is 60 basis points higher than the 3.8% predicted in June.

- Additionally, the panel projected slightly higher inflation in the third fiscal quarter, increasing the estimate by 10 basis points to 4.7%, signaling that the near-term inflation outlook is less reassuring than it was two months ago.

- Mr. Das noted that in June, vegetable prices contributed about 35% to headline inflation, and the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) predicted that price pressures on vegetables would likely persist through the festive season until early November, adding to retail inflation.

Conclusion:

The MPC also suggested that core inflation may have bottomed out, highlighting risks from the spillover of food prices and the potential impact of mobile tariff revisions on broader non-food inflation. Policymakers emphasized that without ensuring sustained price stability, economic growth may remain fragile.

No Population Census — in the Dark Without Vital Data

Context:

The Indian decadal Census has been delayed by over three years, raising significant concerns about the repercussions of not having this vital data. There is a widespread misconception among officials that the Census can be replaced with alternative methods of counting the population. However, the Census provides far more than just a population count. It collects a broad range of locational, familial, and individual data crucial for understanding the complete dynamics of a changing population.

Relevance:

- GS1- Population and Associated Issues

- GS2- Government Policies & Interventions

Mains Question:

The Census is not limited to being a mere population count; it includes a wide range of crucial locational, familial and individual information. In this context, analyse the repercussions of a delay in census. (10 Marks, 150 words).

Associated Issues:

- One of the primary issues with skipping the Census is the reliability of large-scale surveys, such as the National Family Health Survey and the Periodic Labour Force Survey, which are based on a Census framework that is now 15 years old.

- The past decade and a half has likely seen significant changes not only in population size and composition but also in areas such as education, occupation, employment, health (including the impact of COVID-19), and livelihoods.

- Delaying the Census, therefore, seems highly irresponsible, and considering alternatives to it is shortsighted.

- Moreover, there is growing demand for a caste Census, driven more by political motivations than by a genuine need for development planning.

- This demand highlights a limited understanding of the Census’s importance for refining strategies aimed at human welfare.

- Missing the 2021 Census is inexcusable, especially considering that a general election was held during the same period despite numerous uncertainties.

- The logistics required for a Census are comparable to those of an election, which suggests that the delay might be more about avoidance than logistical challenges.

- Without up-to-date Census data, evaluating the effectiveness of government schemes and programs will be misleading, as there will be no accurate baseline for comparison.

The Urgency of Conducting a Population Census:

- The need for an immediate population Census is crucial, especially given India’s rapid demographic transition and the resulting demographic dividend.

- A Census is essential for accurately capturing changes in population structure, including familial arrangements, locational distribution, and occupational composition.

- Without a current Census, surveys become less reliable and representative, which undermines the generation of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicators.

- Consequently, any claims of progress based on these indicators may be questioned due to their statistical shortcomings.

- Accurate demographic data, as revealed by global population projections, are particularly important for large countries like India and China, where population dynamics significantly influence global trends.

- Relying on estimates based on outdated trends and projections is insufficient; the Census provides the necessary reality check for understanding these changes.

- Reducing the Census to merely a population count is a misunderstanding that must be corrected. In the context of the SDGs, there is a strong emphasis on generating a wide array of indicators, disaggregated to levels below the national average.

- These indicators require standardization based on detailed population data, segmented by age, sex, and other attributes. Without a recent Census, approximations or survey-based estimates are inadequate for representing the evolving realities of the population.

The Caste Census Debate:

- While the urgency of conducting a population Census seems distant, political leaders are increasingly calling for a caste Census to further their agendas.

- A caste audit in India, especially when everything is portrayed as positive, seems misplaced.

- Historically, the Census included caste data in its early stages, but its discontinuation suggests there was a valid reason for this change.

- It’s important not to be misled into thinking that a caste audit is driven by a genuine desire to understand the inclusion of different caste groups.

- Instead, it is largely aimed at establishing differential entitlements by citing a lack of representation and deprivation.

- However, focusing solely on tangible assets is a limited way to assess deprivation, especially when there is no systematic evaluation of mobility in education and occupation, despite long-standing affirmative action.

Conclusion:

Delaying the Census may benefit the state, allowing it to claim progress based on numerical data without the proper denominator needed to calculate accurate indicators. The scientific community must advocate for the immediate resumption of the Census to dispel the illusion that surveys and other administrative statistics can replace it. This raises the key concern: is the Census simply delayed, or is there an intentional effort to avoid it altogether?