CONTENTS

- Producing Better Labor Statistics

- Implementing the Street Vendor’s Act

Producing Better Labor Statistics

Context:

The continual evolution of labor institutions is driven by both objective factors, such as changes in product markets, technology, trade, and investment, and subjective factors, including the orientations of involved agencies. This dynamic applies to the industrial relations system and labor market (IRS-LM), where variables like trade unions, collective bargaining, and strikes are in flux. Reforms in this domain typically address substantive issues and procedural aspects.

Relevance:

GS Paper – 3

- Employment

- Inclusive Growth

Mains Question:

Discuss the concerns associated with the compilation of labor statistics in India. What role can trade unions play in this regard? (10 Marks, 150 Words).

Obtaining Labor Statistics:

- One crucial procedural element is social dialogue, which facilitates consensus-building through debate, ultimately informing legal and policy actions.

- However, this process often lacks evidence-based arguments, resulting in the propagation of class-based opinions unsupported by credible data or experience.

- The Indian Labour Conference (ILC), a key social dialogue agency, has regrettably devolved into a mere forum for discussion without meaningful outcomes.

- Unlike economic and industrial data, labor statistics lack rigor. While entities like the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) and the National Sample Survey Office provide robust data, their coverage of IRS-LM-related information is limited.

- The Labour Bureau offers statistics on various industrial relations and labor metrics but primarily relies on administrative data generated during labor law implementation.

- Moreover, data on work stoppages are collected voluntarily, and the composition and scope of Labor Bureau data have remained largely unchanged over the years.

Employers Rationale for Reforms in Labor Statistics:

Let’s examine three persistent arguments for reform frequently advocated by employers and neoliberal scholars.

- Employers often criticize the labor inspection system, labeling it as an “Inspector-Raj,” and call for its overhaul, likely due to their limited exposure to its workings.

- They express dissatisfaction with state governments’ reluctance to approve applications for retrenchment or establishment closures and advocate for restrictions on the right to strike, preferring non-unionized workplaces.

- Similarly, certain academics and global bodies like the World Bank/International Monetary Fund, sharing similar predispositions to employers, consistently produce studies supporting the positive effects of reforms while dismissing opposing views. For instance, despite significant flaws in studies utilizing methodologies like those employed by Besley and Burgess (B&B) in their 2004 analysis on labor regulation impacts, employers and others continue to exploit them to advocate for various reforms, including hiring and firing policies.

Role of Trade Unions in Obtaining Labor Statistics:

Gathering Information:

In response to these reform arguments, trade unions should have gathered pertinent information and statistics on inspections, such as the number of authorized inspectors versus those actually employed, the extent of inspections conducted compared to the total universe, and the frequency of inspections.

Reforms Related to Hiring and Closure:

Concerning reforms related to hiring and closure practices, trade unions have failed to gather data on retrenchment and closure applications filed under Chapter V-B, along with the permissions granted or denied by labor departments. Most states do not publish such data, except for a limited period in Maharashtra.

Regarding Strikes:

- Regarding strikes, the Industrial Relations Code of 2020 has made legal strikes nearly unattainable, imposing heavy penalties for illegal strikes.

- Trade unions could have utilized strike and lockout data published by the Labor Bureau, revealing that lockouts occur more frequently and result in more lost workdays than strikes during the post-reform period.

- This evidence could have challenged the necessity of introducing harsher strike clauses in the Industrial Relations Code.

Compiling Statistics:

- Trade unions are in a favorable position to compile statistics on various aspects of the industrial relations system and labor market at the establishment level. While employer organizations such as NASSCOM generate statistics on the IT industry, these are often used indiscriminately.

- In essence, trade unions should prioritize the production of labor statistics, conduct research on the industrial relations system and labor market, establish active and productive collaborations with academics, and employ academic studies to formulate evidence-based arguments in forums such as the Indian Labor Conference.

Conclusion:

The above actions would likely prompt broader society and the government to advocate for labor statistics reform, granting strikes public legitimacy. This May Day in 2024, trade unions should commit to undertaking these measures, knowing that such pursuits may lead to reforms within statistical agencies like the Labor Bureau.

Implementing the Street Vendor’s Act

Context:

Ten years have passed since the enactment of the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act on May 1, 2014, representing a significant milestone following nearly four decades of legal discourse and the dedicated efforts of street vendor movements across India. Initially hailed as a progressive legislation, the Act now encounters numerous challenges in its implementation.

Relevance:

- GS2- Government Policies and Interventions

- GS-3- Inclusive Growth

Mains Question:

Celebrated as a progressive legislation at the time of its inception, the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014 now faces numerous challenges in its implementation. Examine. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

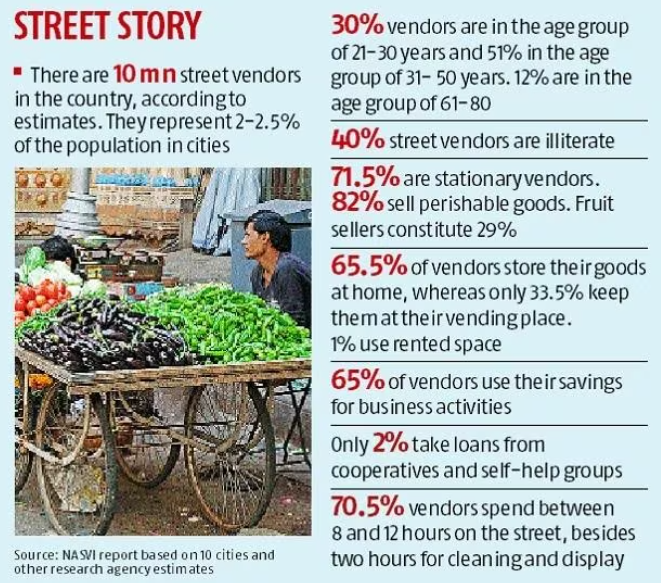

Street Vendors in India:

- The legislation acknowledges the multifaceted roles of street vendors, estimated to comprise 2.5% of any city’s population.

- These vendors serve as essential providers of daily services, offering vital links in the food, nutrition, and goods distribution chain at affordable prices.

- For many migrants and urban poor, vending provides a modest yet consistent source of income.

- Moreover, street vendors contribute to the cultural fabric of India, with iconic dishes like Mumbai’s vada pav and Chennai’s roadside dosai embodying their significance.

Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014:

- The Act was designed to recognize and regulate this reality, aiming to protect and regulate street vending in cities through State-level regulations and schemes, overseen by Urban Local Bodies (ULBs).

- It delineates the roles and responsibilities of vendors and various levels of government, emphasizing the positive urban role of vendors and the imperative of livelihood protection.

- Notably, it commits to accommodating all existing vendors in designated vending zones and issuing vending certificates.

- The Act establishes participatory governance structures, such as Town Vending Committees (TVCs), where street vendor representatives constitute a significant proportion of members, including a mandated representation of women vendors.

- These committees are tasked with ensuring the inclusion of all existing vendors in vending zones and provide mechanisms for addressing grievances and disputes through the proposed Grievance Redressal Committee, chaired by a civil judge or judicial magistrate.

- In theory, these provisions set a crucial precedent for inclusive and participatory approaches to address street vending needs in cities. However, in practice, numerous challenges remain in realizing the Act’s vision.

Challenges in the Act’s Implementation:

Administrative Level Challenges:

- Firstly, on an administrative level, there has been a notable surge in harassment and evictions of street vendors, despite the Act’s emphasis on their protection and regulation.

- This often stems from an outdated bureaucratic mentality that perceives vendors as illegal entities to be removed.

- Additionally, there is a widespread lack of awareness and understanding about the Act among state authorities, the general public, and the vendors themselves.

- Town Vending Committees (TVCs) frequently remain under the control of local city authorities, with limited input from street vendor representatives.

- Moreover, the representation of women vendors in TVCs is often merely symbolic.

Governance Level Challenges:

- Secondly, at the governance level, existing urban governance mechanisms frequently lack strength. The Act fails to integrate effectively with the framework established by the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act for urban governance.

- Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) often lack adequate authority and resources. Initiatives like the Smart Cities Mission, which prioritize top-down policy directives and focus primarily on infrastructure development, typically neglect the Act’s provisions for the integration of street vendors into city planning.

Societal Level Challenges:

- Thirdly, at the societal level, the prevailing notion of the ‘world-class city’ tends to be exclusionary.

- This viewpoint marginalizes and stigmatizes street vendors as hindrances to urban progress rather than recognizing them as legitimate contributors to the urban economy.

- These challenges manifest in city layouts, urban policies, and public perceptions of neighborhoods.

Way Forward:

- While the Act is characterized by its progressive and comprehensive nature, its successful implementation necessitates support, which paradoxically may require top-down direction and management, initially originating from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.

- However, over time, this oversight should be decentralized to ensure effectiveness in addressing the diverse needs and contexts of street vendors across the nation.

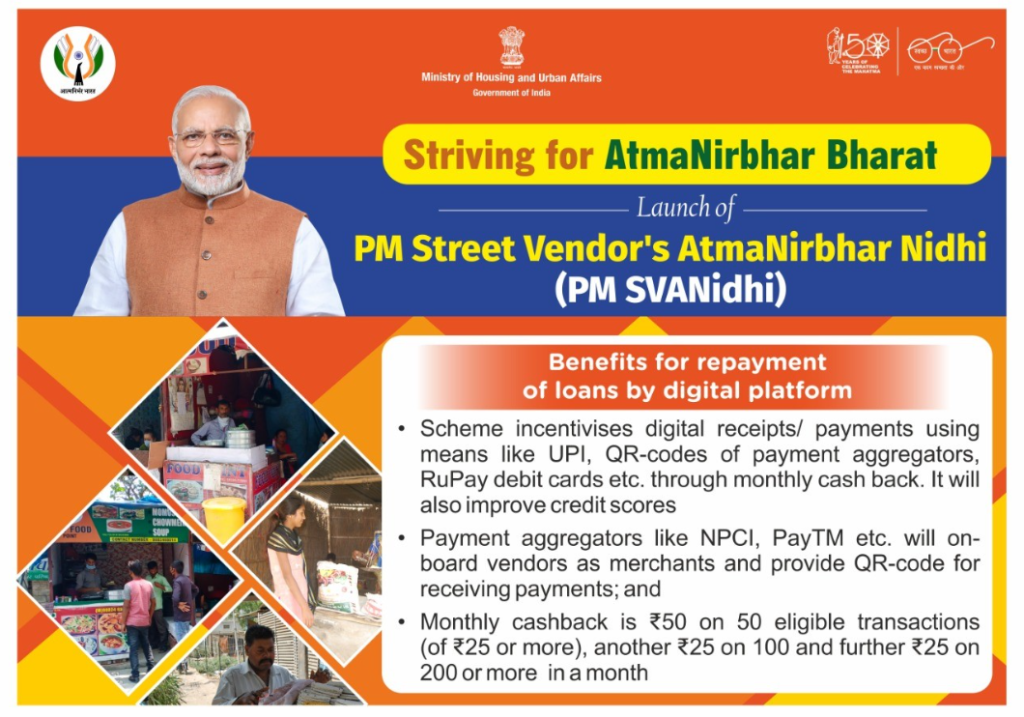

- Initiatives like PM SVANidhi, a micro-credit facility for street vendors, serve as positive examples in this regard. There is a pressing need to decentralize interventions, bolster the capacities of Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) to plan for street vending in cities, and transition from authoritative department-led actions to inclusive deliberative processes at the Town Vending Committee (TVC) level.

- Urban schemes, city planning guidelines, and policies must be revised to incorporate provisions for street vending.

- Furthermore, the Act now confronts new challenges, including the impact of climate change on vendors, a proliferation in the number of vendors, competition from e-commerce platforms, and diminished incomes.

- To address these evolving challenges, the Act’s broad welfare provisions must be creatively utilized to meet the emerging needs of street vendors.

- Additionally, the sub-component on street vendors within the National Urban Livelihood Mission must adapt to acknowledge the altered realities and facilitate innovative measures to address these needs.

Conclusion:

The experience of implementing the Street Vendors Act underscores the intricate interplay between contested spaces, urban labor, and governance, offering valuable insights for future legislative endeavors and their execution.