Contents

- Looking beyond the Forest Rights Act

- India as a regional leader, not a victim of circumstance

Looking beyond the Forest Rights Act

Context:

- The Forest Rights Act (FRA) has been in existence for 15 years and as of April 2020 the Ministry of Tribal Affairs had received over 42 lakh claims, of which titles were distributed to 46% of the applicants.

- If the Forest Department’s views are considered, the implementation process is more or less over.

- But the supporters of tribal rights allege that the Department is overlooking the genuine claims of the tribal people.

- Despite the Ministry being the implementing agency, the role of the Forest Department in granting titles is crucial because the lands claimed are under its jurisdiction.

Relevance:

GS-II: Social Justice and Governance (Issues Related to SCs & STs, Management of Social Sector/Services, Government Policies and Interventions)

Dimensions of the Article:

- History of the Recognition of Forest Rights legislation

- Forest Rights Act, 2006

- Implementation of the Forest Rights Act 2006

- Challenges in implementation of the Forest Right Act

- Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006 Criticism

- Ways to improve

History of the Recognition of Forest Rights legislation

- In the colonial era, the British diverted the abundant forest wealth of the nation to meet their economic needs. While the procedure for settlement of rights was provided under statutes such as the Indian Forest Act, 1927, these were hardly followed.

- As a result, tribal and forest-dwelling communities, who had been living within the forests in harmony with the environment and the ecosystem, continued to live inside the forests in tenurial insecurity, a situation which continued even after independence as they were marginalised.

- The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, also known as the Forest Rights Act was enacted to protect the marginalised socio-economic class of citizens and balance the right to the environment with their right to life and livelihood.

Forest Rights Act, 2006

- Schedule Tribes and Other Forest Dwellers Act or Recognition of Forest Rights Act came into force in 2006. The Nodal Ministry for the Act is Ministry of Tribal Affairs.

- It has been enacted to recognize and vest the forest rights and occupation of forest land in forest dwelling Scheduled Tribes and other traditional forest dwellers, who have been residing in such forests for generations, but whose rights could not be recorded.

- This Act not only recognizes the rights to hold and live in the forest land under the individual or common occupation for habitation or for self-cultivation for livelihood, but also grants several other rights to ensure their control over forest resources.

- The Act also provides for diversion of forest land for public utility facilities managed by the Government, such as schools, dispensaries, fair price shops, electricity and telecommunication lines, water tanks, etc. with the recommendation of Gram Sabhas.

- Rights under the Forest Right Act 2006:

- Title Rights- ownership of land being framed by Gram Sabha.

- Forest management rights– to protect forests and wildlife.

- Use rights- for minor forest produce, grazing, etc.

- Rehabilitation– in case of illegal eviction or forced displacement.

- Development Rights– to have basic amenities such as health, education, etc.

Implementation of the Forest Rights Act 2006

- Gram Sabha is the authority to initiate a process to vest rights on marginally and tribal communities after assessment of the extent of their needs from forest lands.

- Gram Sabha after its assessment, receives claims of the communities, consolidates and verify these to help them exercise their rights

- Gram Sabha then passes such a resolution to sub-divisional level committee (formed by the state governments.)

- If one or more communities are not satisfied by such a resolution, may file a petition to sub-divisional level committee

- Sub-Divisional Level committee after its assessment, passes the resolution to Sub-divisional officer to district level committee for its final decision

- The district-level committee’s decisions are considered final and binding

- A state-level monitoring committee is constituted by the state government to monitor the process of recognition of these rights

- The officers included in the sub-divisional level committee, district-level committee and state-level monitoring committee include:

- Officers of Department of Revenue of state government

- Officers of Department of Forests of state government

- Officers of Department of Tribal Affairs of state government

- Three members of Panchayati Raj Institutions including two Scheduled Tribes members and at least one woman

- The Act recognizes and vest the forest rights and occupation in Forest land in Forest Dwelling Scheduled Tribes (FDST) and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (OTFD) who have been residing in such forests for generations.

- The Act identifies four types of rights:

- Title rights: It gives FDST and OTFD the right to ownership to land farmed by tribals or forest dwellers subject to a maximum of 4 hectares. Ownership is only for land that is actually being cultivated by the concerned family and no new lands will be granted.

- Use rights: The rights of the dwellers extend to extracting Minor Forest Produce, grazing areas etc.

- Relief and development rights: To rehabilitate in case of illegal eviction or forced displacement and to basic amenities, subject to restrictions for forest protection.

- Forest management rights: It includes the right to protect, regenerate or conserve or manage any community forest resource which they have been traditionally protecting and conserving for sustainable use.

Challenges in implementation of the Forest Right Act

- The Tribals majorly received lesser rights than claimed due to the fact that they believed if they claimed their right, they may lose the smaller claim as well. This information asymmetry had led to the further alienation of the tribal persons from the mainstream.

- The land allotted to the Tribal persons is mostly small, of poor quality and not very fertile. The lack of irrigation facilities and labour-wage economy further destroy their productivity and profitability. The declining industry of local cigars in Chhattisgarh is a prime example of the same.

- Despite the confirmation of forming a Forest Rights Committee from the grassroots level, there has not been any such activity in many places, it was observed.

- Various developmental schemes for rural development such as Deendayal Upadhyaya Gram Jyoti Yojana, Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram, etc. have not been able to empower the vulnerable sections and failed to allow for the assertion of political space.

- A series of legislation– amendments to the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Act and a host of amendments to the Rules to the FRA- undermine the rights and protections given to tribal in the FRA, including the condition of “free informed consent” from gram Sabhas for any government plans to remove tribal from the forests and for the resettlement or rehabilitation package.

- The process of documenting communities’ claims under the FRA is intensive — rough maps of community and individual claims are prepared democratically by Gram Sabhas. These are then verified on the ground with annotated evidence, before being submitted to relevant authorities.

- There is a reluctance of the forest bureaucracy to give up control with FRA being seen as an instrument to regularise encroachment. This is seen in its emphasis on recognising individual claims while ignoring collective claims — Community Forest Resource (CFR) rights as promised under the FRA — by tribal communities. To date, the total amount of land where rights have been recognised under the FRA is just 3.13 million hectares, mostly under claims for individual occupancy rights.

- In almost all States, instead of Gram Sabhas, the Forest Department has either appropriated or been given effective control over the FRA’s rights recognition process. This has created a situation where the officials controlling the implementation of the law often have the strongest interest in its non-implementation, especially the community forest rights provisions, which dilute or challenge the powers of the forest department.

- Saxena Committee pointed out several problems in the implementation of FRA. Wrongful rejections of claims happen due to lack of proper enquiries made by the officials.

Forest Rights Act (FRA) 2006 Criticism

- The debate on the issue of the act leading to even more encroachment of already troubled forest lands has started.

- Though the act tries to focus on the needs of the forest dwellers, it defeats the purpose when the eviction rate of families from these lands increases as their claims on these lands are not accepted by the government.

- The role of the sub-divisional level committee is always questioned as they have been given the important right to make a decision on the needs and claims of the marginal communities on the piece of forest lands.

- Issues have arisen from the part of forest departments who have been seen unwilling to give their forest lands. Role of forest department to let the forest dwellers sow in the forest the reap the benefits is criticized as tribes like Baigas have blamed the department to not support their claim over the land.

- The tribes and communities also lack the capability to prove their occupancy over the forest land and the law turns out to be weak to strengthen their claim.

- Government’s role of allowing commercial plantations in degraded land is also debated and questioned as the degraded land makes 40% of forests.

Ways to improve

- Innovative Techniques: The techniques of horticulture must be provided to the tribals so that they may increase their productivity and afford a better quality of life.

- Involvement of Civil Society: Various organizations such as in Dang, Gujarat allowed for the hand-holding of the beneficiaries at every step.

- Kerala Model: The promotion of eco-tourism and medico-tourism to safeguard the interests of the tribals is another positive step. Also providing skill-based education with assured jobs on a large scale in proportion to the demand would do wonders in these areas.

-Source: The Hindu

India as a regional leader, not a victim of circumstance

Context:

Addressing an Indian Ocean Conference in December 2021, India’s External Affairs Minister listed the American pull-out from Afghanistan and the novel coronavirus pandemic as the two developments that have the most heightened uncertainties in the region.

Relevance:

GS-II: International Relations (India’s Neighbours, Foreign Policies affecting India’s Interests, India’s Foreign Policy)

Dimensions of the Article:

- Indian Ocean Conference 2021

- What are the issues linked to India’s Afghan policy?

- What are the issues associated with India’s policy in countering China?

- What needs to be done to counter China’s increasing role in India’s neighborhood?

- Conclusion

Indian Ocean Conference 2021

- The Indian Ocean Conference is an annual conference that brings together a large group of nations whose predominant identity is often more sub-regional as it includes Heads of States/Governments, Ministers, thought leaders, scholars, diplomats, bureaucrats and practitioners from across the region on a single platform.

- The conference is being organised by a Delhi based Think tank – India Foundation – in collaboration with the RSIS Singapore, Institute of National Security Studies (INSS), Sri Lanka, and the Emirates Centre for Strategic Studies and Research (ECSSR), UAE.

- India’s Union Minister of External Affairs (EAM) visited Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE) to attend the 5th Indian Ocean Conference in December 2021.

- The theme of the conference was ‘Indian Ocean: Ecology, Economy, Epidemic’.

- The Conference is chaired by Sri Lankan President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa & Vice Chairs are S.Jaishankar, Vivian Balakrishnan, Sayyid Badr Bin Hamad Bin Hamoud Al Busaidi.’

- India’s External Affairs Minister listed the following issues linking them to India’s neighbourhood:

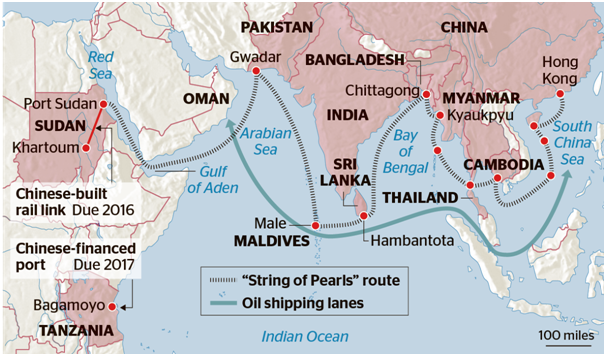

- The rise of China that has resulted in territorial tensions

- American pull-out from Afghanistan

- The challenges posed by the novel coronavirus pandemic.

What are the issues linked to India’s Afghan policy?

- Firstly, India failed to recognize the U.S.’s Afghan policy, especially after it signed the Doha Agreement of February 2020. The Doha Agreement made the Taliban a legitimate interlocutor, without the condition of a ceasefire. India merely blindsided with the U.S. and the Troika Plus members (Russia, China, and Pakistan) without voicing out its interest. It paved the way for the fall of the Afghan republic.

- Secondly, India failed to secure its friends in Afghanistan. India canceled all the visas that had been granted to Afghans prior to August. India resisted allowing Afghans, looking for shelter in India. Afghans felt betrayed by a country they once considered “second home”.

- Thirdly, India has been reluctant to support or host those who pose a counter to the Taliban regime today. For instance, the “Resistance Front” led by Ahmad Massoud and former Vice-President Amrullah Saleh.

It was in contrast to the 1990s when India kept up its contacts with the Northern Alliance, supported their families in India, and admitted thousands of other Afghan refugees. This response helped India to build closer ties with Afghanistan after the Taliban was defeated in 2001.

What are the issues associated with India’s policy in countering China?

- Firstly, The Government’s reservation towards acknowledging the Chinese actions in Indian territory is seen as an act of low self-esteem.

- Secondly, despite dozens of rounds of military and ministerial talks, the Government is unaware of the reasons for the Chinese action. This exposes a lack of strategic thinking.

- Those who have analysed the situation more closely have pointed out few objectives behind China’s aggression at the LAC:

- China is looking to reclaim the territories that it has lost over hundreds of years, from the South China Sea to Tibet

- China is looking to restrict India’s recent efforts at building border infrastructure, bridges, and roads right up to the LAC

- China is also looking to restrict any possible perceived threat to Xinjiang and Tibet

- China is looking to restrict India’s ability to threaten China’s key Belt and Road project, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), including a second link highway it plans from the Mustagh pass in occupied Gilgit-Baltistan to Pakistan

- China is also looking to blunt India’s plan to reclaim Aksai Chin and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK) militarily.

What needs to be done to counter China’s increasing role in India’s neighborhood?

- First, India should not make spaces for China in its immediate neighborhood. For instance, India’s failure in keeping its promises to provide vaccines to its neighbors has impacted India’s image as a leader.

- Second, India can counter China by invoking its democratic system, which is admired by its neighbors. But before that, India should adhere to democratic principles such as pluralism, representative, inclusive power that respects the rights of each citizen, the media, and civil society.

- Thirdly, India should forge its alliance with other countries more carefully, keeping in mind the interest of its neighbors.

Conclusion

- Recent surveys by think tanks Carnegie and the Centre for Social and Economic Progress have found that India is a preferred strategic partner for most of the countries in the neighbourhood. However, possible Indian collaborations with the U.S., Japan, Europe, etc. are being seen as “anti-China” collaborations, which these countries would want to avoid.

- These partnerships also hamper India’s ability to stand up for its neighbours when required. For instance, India could not stand up for Bangladesh when the U.S. chose to slap sanctions on Bangladesh’s multi-agency anti-terror Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) force. Thus, India must stop behaving like a “middle power” and decide its best interests and chart its own course of action in its neighbourhood.

-Source: The Hindu