Contents

- Five years since demonetisation: What has changed?

- Does India have a right to burn fossil fuels?

Five years since demonetisation: What has changed?

Context:

November 8, 2021 marks five years of demonetisation in India.

Relevance:

GS-III: Indian Economy (Fiscal Policy, Government Policies and Initiatives)

Dimensions of the Article:

- About the Demonetization in 2016

- Impact of demonetization

- The euphoria surrounding the crackdown on “Black Money”

- Capitalising on the moral economy of the poor

- Has demonetisation pushed India towards a cashless trajectory?

About the Demonetization in 2016

- Demonetisation is an act of withdrawing the status of currency as legal tender. It occurs whenever national currency of a country is changed.

- According to Reserve Bank of India (RBI), currency with public is defined as “Total currency in circulation minus cash available with banks”. Currency in Circulation is defined as cash or currency available within a country for the purpose of conducting transactions between consumers and businesses.

- Under this act, current form or forms of money is pulled from circulation and are replaced with new notes or coins.

- Demonetisation was announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2016. With this move, Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes were withdrawn as a legal tender across the country. This move was aimed at eliminating black money.

- Demonetisation is done with the objective of:

- Discouraging the use of high-denomination notes for illegal transactions. It curbs the use of black money.

- Encouraging digitisation of commercial transactions and formalising the economy. Thus, it boosts government tax revenues.

Impact of demonetization

- Unlike the limited impact of similar events in 1946 and 1978, the latest demonetisation in 2016 resulted in widespread disruption in the economy, whose aftershocks are still being felt by society.

- The majority of observers have opined that this policy was a failure as only a fraction of its declared objectives could be achieved.

- Interestingly, more than 99.3% of cash returned to the system, pointing towards money laundering routes.

- Rubbing more salt to the wound, data shows that the cash in circulation now exceeds even the pre-demonetisation levels.

- On November 4, 2016, currency with public was around Rs. 17.97 lakh crore which declined to Rs 7.8 lakh crore in January 2017 following demonetisation.

- Demonetisation led to liquidity shortage in economy. Post demonetisation, demands fell, businesses faced a crisis and gross domestic product (GDP) growth decreased to 1.5%.

The euphoria surrounding the crackdown on “Black Money”

- The deeply satisfying idea of striking a powerful blow through dramatic action against black money has always been in the psyche of the public. More often than not, it has been influenced by the stuff of epics, cinematic experiences and moral terms.

- Contrary to the popular belief, the lion’s share of black money is earned through perfectly legal activities rather than income from corruption or criminal activities.

- Moreover, black money is not mostly kept, in stacks of currency notes and gold, hoarded in safes, boxes, or secret cupboards, except in small quantities, but is mostly accumulated through real estate and other assets.

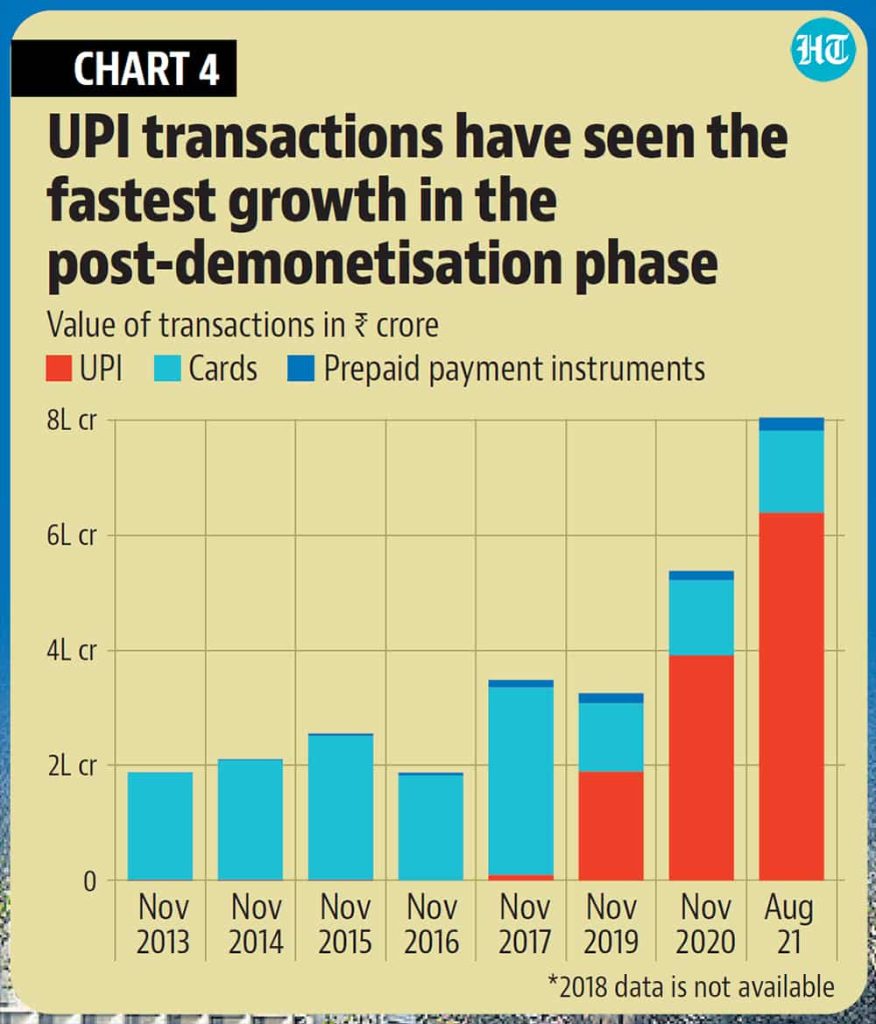

- We observed seemingly the narrative getting changed and focus from black money and fake currency to digital/cashless payments being elevated and taking the centre stage.

Capitalising on the moral economy of the poor

- The ideals of collective sacrifice, nationalism and patriotism have always been at the deeply entrenched soft corners among the masses and invoking high moral values is a low hanging fruit for policymakers.

- For the poor, any endeavour towards penalising the rich is far more attractive than achieving social justice and equity.

Has demonetisation pushed India towards a cashless trajectory?

- Describing demonetisation as a nudge towards digital payments, which is how the policy is justified by many people today, was an after-thought although the original policy announcement did talk about reducing the amount of cash in circulation in the Indian economy.

- The Prime Minister said that the magnitude of cash in circulation is directly linked to the level of corruption. Inflation becomes worse through the deployment of cash earned in corrupt ways. The misuse of cash has led to artificial increase in the cost of goods and services like houses, land, higher education, health care and so on.

- While digital payments have increased significantly since demonetisation (more on this later), whether or not India has become a cashless economy post demonetisation is a different question.

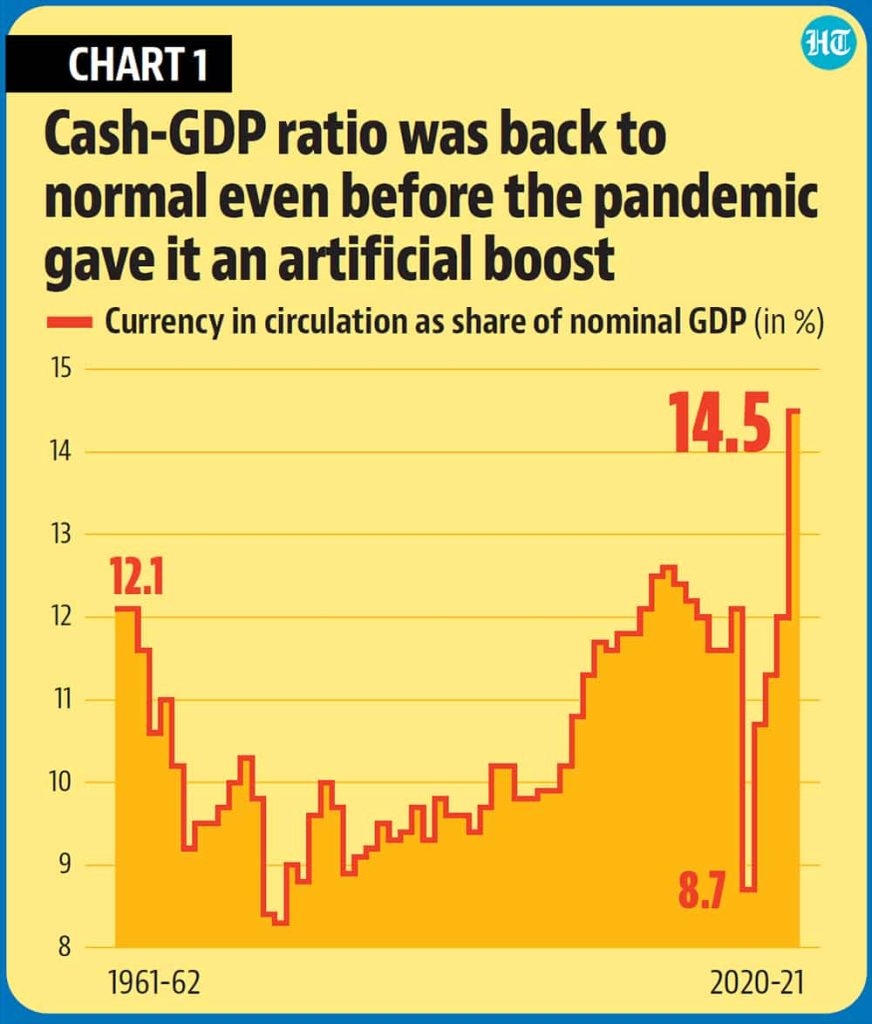

- The best metric to answer this question is to look at the ratio of currency in circulation (at the end of a fiscal year) and the nominal GDP (in that fiscal year).

- Currency in circulation was 12.1% of India’s nominal GDP in 2015-16, the year before demonetisation. It plummeted to 8.7% in 2016-17 as the banking system was struggling to put cash back into the system after demonetisation. Since then, this ratio has climbed steadily and it reached 12% in 2019-20.

- A restoration of currency in circulation to nominal GDP ratio shows that there was no significant impact of demonetisation until 2019-20. This number reached an all-time high of 14.5% in 2020-21.

-Source: The Hindu

Does India have a right to burn fossil fuels?

Context:

During the recent United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26), India has, for the first time, committed to achieving the net-zero emission target by 2070.

Relevance:

GS-III: Environment and Ecology (Environmental Pollution and Degradation, Conservation of Environment and Ecology, Foreign Agreements and Treaties affecting India’s Interests)

Dimensions of the Article:

- India and the Carbon budget framework

- About the Pledges

- Why should developing countries aim for development without increasing carbon emission?

India and the Carbon budget framework

- India has neither historically emitted nor currently emits carbon anywhere close to what the global North has, or does, in per capita terms.

- If anything, the argument goes, it should ask for a higher and fairer share in the global carbon budget.

- There is no doubt that this carbon budget framework is an excellent tool to understand global injustice but to move from there to our ‘right to burn’ is a big leap.

About the Pledges

- The Indian PM surprised observers across the world with some ambitious, commendable and unconditional five pledges (Panchamrit) on India’s decarbonisation during his speech at COP26:

- Increase non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GWs by 2030.

- Meet 50 percent of energy requirements from renewables by 2030.

- Reduce the total projected carbon emissions by 1 BTs by 2030.

- Reduce the carbon intensity of the economy by less than 45 percent.

- Achieve net zero carbon by 2070.

- Although these commitments appear to be our new tryst with destiny in terms of achieving sustainable development goals, more clarity on each of these targets could help in realising a few of the targets, if not all.

Why should developing countries aim for development without increasing carbon emission?

Reducing the cost of renewable energy

- Normally the argument in favour of coal is on account of its cost, reliability and domestic availability.

- Recent data show that the levelised cost of electricity from renewable energy sources like solar (photovoltaic), hydro and onshore wind has been declining sharply over the last decade and is already less than fossil fuel-based electricity generation.

- On reliability, frontier renewable energy technologies have managed to address the question of variability of such sources to a large extent and, with technological progress, it seems to be changing for the better.

- As for the easy domestic availability of coal, it is a myth.

- India is among the largest importers of coal in the world, whereas it has no dearth of solar energy.

Following different development model

- During the debates of post-colonial development in the Third World, there were two significant issues under discussion — control over technology and choice of techniques to address the issue of surplus labour.

- India didn’t quite resolve the two issues in its attempts of import-substituting industrialisation which worsened during the post-reform period. But it can address both today.

- The abundance of renewable natural resources in the tropical climate can give India a head start in this competitive world of technology.

- South-South collaborations can help India avoid the usual patterns of trade between the North and the South, where the former controls technology and the latter merely provides inputs.

- And the high-employment trajectory that the green path entails vis-à-vis the fossil fuel sector may help address the issue of surplus labour, even if partially.

- Such a path could additionally provide decentralised access to clean energy to the poor and the marginalised, including in remote regions of India.

Limitation of addressing global injustice in terms of a carbon budget

- The framework of addressing global injustice in terms of a carbon budget is quite limiting in its scope in more ways than one.

- Such an injustice is not at the level of the nation-states alone; there is such injustice between the rich and the poor within nations and between humans and non-human species.

- A progressive position on justice would take these injustices into account instead of narrowly focusing on the framework of nation-states.

- Moreover, it’s a double whammy of injustice for the global South when it comes to climate change.

- Not only is it not primarily responsible, but the global South, especially its poor, will unduly bear the effect of climate change because of its tropical climate and high population density along the coastal lines.

- So, arguing for more coal is like shooting oneself in the foot.

-Source: The Hindu