CONTENTS

- Takeaways from Forest Report

- Global Risks Report 2022

- Krishna Water Dispute

Takeaways from Forest Report

Context:

The Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MoEFCC) released the India State of Forest Report (ISFR) 2021.

- The report showed a continuing increase in forest cover across the country, but experts flagged some of its other aspects as causes for concern, such as a decline in forest cover in the Northeast, and a degradation of natural forests.

Relevance:

GS III- Environment and Ecology

Dimensions

- What is the India State of Forest Report?

- ISFR 2021: What are the key findings?

- What kind of forests are growing?

- Reasons for the decline in the Northeastern states

- What else does the report cover?

- What impact has climate change had?

What is the India State of Forest Report?

- It is an assessment of India’s forest and tree cover, published every two years by the Forest Survey of India under the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change.

- The first survey was published in 1987, and ISFR 2021 is the 17th.

- India is one of the few countries in the world that brings out such an every two years, and this is widely considered comprehensive and robust.

- With data computed through wall-to-wall mapping of India’s forest cover through remote sensing techniques, the ISFR is used in planning and formulation of policies in forest management as well as forestry and agroforestry sectors.

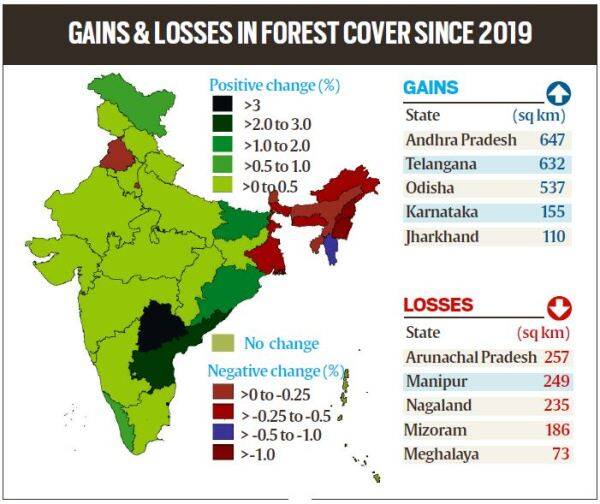

Gains and losses in forest cover since 2019

ISFR 2021: What are the key findings?

- ISFR 2021 has found that the forest and tree cover in the country continues to increase with an additional cover of 1,540 square kilometres over the past two years.

- India’s forest cover is now 7,13,789 square kilometres, 21.71% of the country’s geographical area, an increase from 21.67% in 2019. Tree cover has increased by 721 sq km.

- The states that have shown the highest increase in forest cover are Telangana (3.07%), Andhra Pradesh (2.22%) and Odisha (1.04%).

- Five states in the Northeast – Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Nagaland have all shown loss in forest cover.

- Mangroves have shown an increase of 17 sq km. India’s total mangrove cover is now 4,992 sq km.

- The survey has found that 35.46 % of the forest cover is prone to forest fires. Out of this, 2.81 % is extremely prone, 7.85% is very highly prone and 11.51 % is highly prone

- The total carbon stock in country’s forests is estimated at 7,204 million tonnes, an increase of 79.4 million tonnes since 2019.

- Bamboo forests have grown from 13,882 million culms (stems) in 2019 to 53,336 million culms in 2021.

What kind of forests are growing?

- While ISFR 2021 has shown an increasing trend in forest cover overall, the trend is not uniform across all kinds of forests.

- Three categories of forests are surveyed –

- very dense forests (canopy density over 70%),

- moderately dense forests (40-70%)

- open forests (10-40%).

- Scrubs (canopy density less than 10%) are also surveyed but not categorised as forests.

- Very dense forests have increased by 501 sq km. This is a healthy sign but pertains to forests that are protected and reserve forests with active conservation activities.

- There is a 1,582 sq km decline in moderately dense forests, or “natural forests”.

- The decline, in conjunction with an increase of 2,621 sq km in open forest areas – shows a degradation of forests in the country, with natural forests degrading to less dense open forests.

- Also, scrub area has increased by 5,320 sq km – indicating the complete degradation of forests in these areas, they say.

Reasons for the decline in the Northeastern states:

- The Northeast states account for 7.98% of total geographical area but 23.75% of total forest cover.

- The forest cover in the region has shown an overall decline of 1,020 sq km in forest cover.

- While states in the Northeast continue to have some of the largest forested areas, such as Mizoram (84.5% of its total geographical area is forests) or Arunachal Pradesh (79.3%), the two states have respectively lost 1.03% and 0.39% of their forest cover, while Manipur has lost 1.48 %, Meghalaya 0.43%, and Nagaland 1.88%.

- The decline in the Northeastern states to a spate of natural calamities, particularly landslides and heavy rains, in the region as well as to anthropogenic activities such as shifting agriculture, pressure of developmental activities and felling of trees.

- This loss is of great concern as the Northeastern states are repositories of great biodiversity.

- While natural calamities may have led to much of the loss, the declining forests will in turn increase the impact of landslides.

- It will also impact water catchment in the region, which is already seeing degradation of its water resources. Unlike other states, where forests are clearly managed by the forest department and state governments, the Northeastern states follow a different ownership pattern — community ownership and protected tribal land – which makes conservation activities challenging.

What else does the report cover?

- ISFR 2021 has some new features.

- It has for the first time assessed forest cover in tiger reserves, tiger corridors and the Gir forest which houses the Asiatic lion.

- The forest cover in tiger corridors has increased by 37.15 sq km (0.32%) between 2011-2021, but decreased by 22.6 sq km (0.04%) in tiger reserves.

- Forest cover has increased in 20 tiger reserves in these 10 years, and decreased in 32.

- Buxa, Anamalai and Indravati reserves have shown an increase in forest cover while the highest losses have been found in Kawal, Bhadra and the Sunderbans reserves.

- Pakke Tiger Reserve in Arunachal Pradesh has the highest forest cover, at nearly 97%.

What impact has climate change had?

- The report estimates that by 2030, 45-64% of forests in India will experience the effects of climate change and rising temperatures, and forests in all states (except Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Nagaland) will be highly vulnerable climate hot spots.

- Ladakh (forest cover 0.1-0.2%) is likely to be the most affected.

- India’s forests are already showing shifting trends of vegetation types, such as Sikkim which has shown a shift in its vegetation pattern for 124 endemic species.

- In 2019-20, 1.2 lakh forest fire hotspots were detected by the SNPP_VIIRS sensor, which increased to 3.4 lakh in 2020-21.

- The highest numbers of fires were detected in Odisha, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh.

-Source: Indian Express

Global Risks Report 2022

Context:

The Global Risks Report 2022, an annual report, was released by the World Economic Forum.

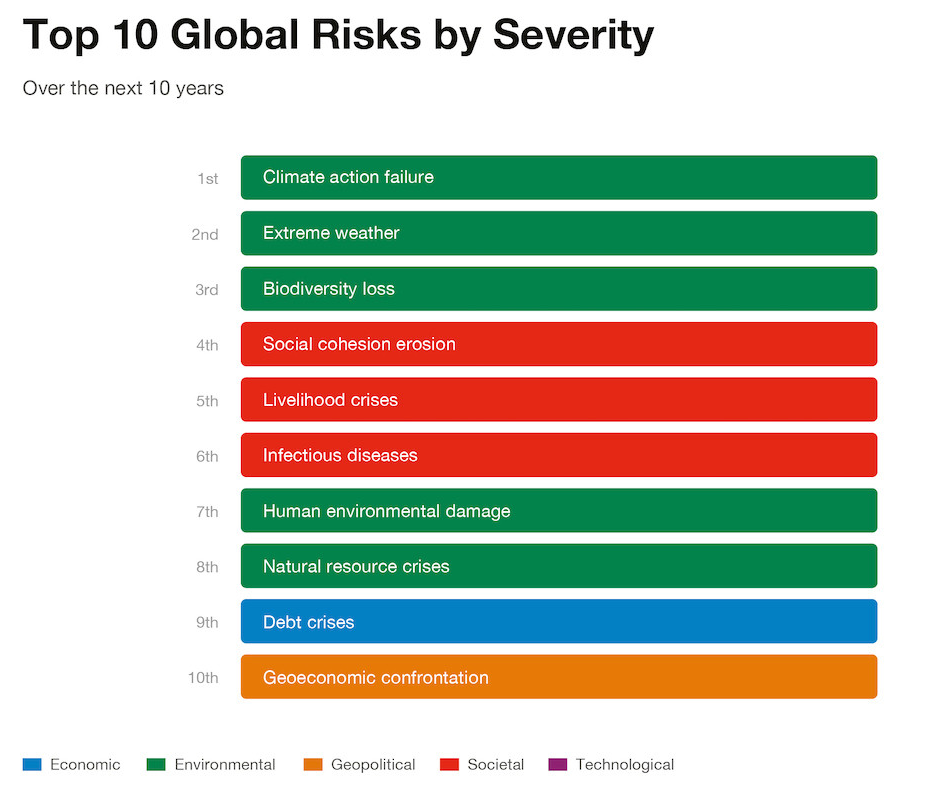

- Climate action failure, extreme weather events and biodiversity loss were perceived by experts as the biggest threats for the global population over the next decade, according to a new report.

Relevance:

GS III- Growth and Development, Important International Institutions

Dimensions:

- About Global Risks Report 2022:

- About World Economic Forum (WEF)

About Global Risks Report 2022:

- It tracks global risk perceptions among risk experts and world leaders in business, government, and civil society.

- It examines risks across five categories: economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal, and technological.

- Environmental factors like human environmental damage and natural resource crisis were also believed to be among the top 10 risks in the period, the Global Risks Report 2022 stated.

- The annual report was based on a survey of 1,000 global experts and leaders in business, government and civil society on their perception of long-term risks to the world. Views of over 12,000 leaders from 124 countries who identified their national short-term risks were also analysed.

- The highest number of respondents thought climate action failure and extreme weather events will be the world’s biggest risks in the next five and 10 years as well, the report showed.

- Impact of Covid-19: The societal and environmental risks have worsened the most since the start of the pandemic.

- “Social cohesion erosion”, “livelihood crises” and “mental health deterioration” are three of the five risks seen as the most concerning threats to the world in the next two years.

- Apart from this, it has significantly contributed to “debt crises”, “cybersecurity failures”, “digital inequality” and “backlash against science”.

- The most serious challenge persisting from the pandemic is economic stagnation.

- Governments, businesses, and societies are facing increasing pressure to transition to net-zero economies.

- In the longer-term horizon, geopolitical and technological risks are of concern too—including “geoeconomic confrontations”, “geopolitical resource contestation” and “cybersecurity failure”.

- Artificial intelligence, space exploitation, cross-border cyberattacks and misinformation and migration and refugees were rated as the top areas of international concerns.

- Growing insecurity in the forms of economic hardship, worsening impacts of climate change and political persecution will force millions to leave their homes in search of a better future.

- The prospect of 70,000 satellite launches in coming decades, in addition to space tourism, raises risks of collisions and increasing debris in space, amid a lack of regulation.

About World Economic Forum (WEF)

- The World Economic Forum is the International Organization for Public-Private Cooperation.

- It was established in 1971 as a not-for-profit foundation and is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. It is independent, impartial and not tied to any special interests.

- The Forum strives in all its efforts to demonstrate entrepreneurship in the global public interest while upholding the highest standards of governance.

Major reports published by WEF:

- Energy Transition Index.

- Global Competitiveness Report.

- Global IT Report (WEF along with INSEAD, and Cornell University)

- Global Gender Gap Report.

- Global Risk Report.

- Global Travel and Tourism Report.

-Source: Down to Earth

Krishna Water Dispute

Focus: Inter- state relations

Why in News?

Recently, two judges of the Supreme Court have recused themselves from hearing a matter related to the distribution of Krishna water dispute between Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

- They cited the reason that they did not want to be the target of partiality since the dispute is related to their home states.

Recusal of Judges

It is the act of abstaining from participation in an official action such as a legal proceeding due to a conflict of interest of the presiding court official or administrative officer.

- When there is a conflict of interest, a judge can withdraw from hearing a case to prevent creating a perception that he carried a bias while deciding the case.

About Krishna River

- Source: It originates near Mahabaleshwar (Satara) in Maharashtra. It is the second biggest river in peninsular India after the Godavari River.

- Drainage: It runs from four states Maharashtra (303 km), North Karnataka (480 km) and the rest of its 1300 km journey in Telangana and Andhra Pradesh before it empties into the Bay of Bengal.

- Tributaries: Tungabhadra, Mallaprabha, Koyna, Bhima, Ghataprabha, Yerla, Warna, Dindi, Musi and Dudhganga.

Constitutional and legal provisions related to water disputes

- Article 262(1) provides that Parliament may by law provide for the adjudication of any dispute or complaint with respect to the use, distribution or control of the waters of, or in, any inter State river or river valley.

- Article 262(2) empowers Parliament with the power to provide by law that neither the Supreme Court nor any other court shall exercise jurisdiction in respect of any such dispute or complaint.

- Under Article 262, two acts were enacted:

- River Boards Act 1956: It was enacted with a declaration that centre should take control of regulation and development of Inter-state rivers and river valleys in public interest. However, not a single river board has been constituted so far.

- The Interstate River Water Disputes Act, 1956 (IRWD Act) confers a power upon union government to constitute tribunals to resolve such disputes. It also excludes jurisdiction of Supreme Court over such disputes.

- Despite Article 262, the Supreme Court does have jurisdiction to adjudicate water disputes, provided that the parties first go to water tribunal and then if they feel that the order is not satisfactory only then they can approach supreme Court under article 136.

- The article 136 gives discretion to allow leave to appeal against order, decree, judgment passed by any Court or tribunal in India.

Major Inter-State River Disputes in India

| River (s) | States |

| Ravi and Beas | Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan |

| Narmada | Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan |

| Krishna | Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Telangana |

| Vamsadhara | Andhra Pradesh & Odisha |

| Cauvery | Kerala, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry |

| Godavari | Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha |

| Mahanadi | Chhattisgarh, Odisha |

| Mahadayi | Goa, Maharashtra, Karnataka |

| Periyar | Tamil Nadu, Kerala |

Active River Water Dispute Tribunals in India

- Krishna Water Disputes Tribunal II (2004) – Karnataka, Telangana, Andra Pradesh, Maharashtra

- Mahanadi Water Disputes Tribunal (2018) – Odisha & Chattisgarh

- Mahadayi Water Disputes Tribunal (2010) – Goa,Karnataka, Maharashtra

- Ravi & Beas Water Tribunal (1986) – Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan

- Vamsadhara Water Disputes Tribunal (2010) – Andra Pradesh & Odisha.

Issues with Interstate Water Dispute Tribunals

- Interstate Water Dispute Tribunals are riddled with Protracted proceedings and extreme delays in dispute resolution. For example, the Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal, constituted in 1990, gave its final award in 2007.

- Interstate Water dispute tribunals also have opacity in the institutional framework and guidelines that define these proceedings and ensure compliance.

- There is no time limit for adjudication. In fact, delay happens at the stage of constitution of tribunals as well.

- Though award is final and beyond the jurisdiction of Courts, either States can approach Supreme Court under Article 136 (Special Leave Petition) under Article 32 linking issue with the violation of Article 21 (Right to Life). In the event the Tribunal holding against any Party, that Party is quick to seek redressal in the Supreme Court. Only three out of eight Tribunals have given awards accepted by the States.

- The composition of the tribunal is not multidisciplinary and it consists of persons only from the judiciary.

- No provision for an adequate machinery to enforce the award of the Tribunal.

- Lack of uniform standards- which could be applied in resolving such disputes.

- Lack of adequate resources- both physical and human, to objectively assess the facts of the case.

- Lack of retirement or term- mentioned for the chairman of the tribunals.

- The absence of authoritative water data that is acceptable to all parties currently makes it difficult to even set up a baseline for adjudication.

- The shift in tribunals’ approach, from deliberative to adversarial, aids extended litigation and politicisation of water-sharing disputes.

- The growing nexus between water and politics have transformed the disputes into turfs of vote bank politics.

-Source: The Hindu