Contents

- SC: Cannot fix time limit in defection pleas

- Indian schools and access to Internet in 2019-20

- WB support to India’s informal working class

- ITU’s Global Cybersecurity Index

- India to Maldives on attacks in media

SC: Cannot fix time limit in defection pleas

Context:

The Supreme Court put on hold a petition to frame guidelines for fixing time limits by which the Speakers of Parliament and the Assemblies should decide defection petitions against MLAs.

Relevance:

GS-II: Polity and Governance (Constitutional Provisions, Legislature and Elections, Executive, Separation of Powers)

Dimensions of the Article:

- What is Defection (Aaya Ram Gaya Ram)?

- 10th Schedule of the Indian Constitution (Anti-Defection Law)

- When do the Legislators face risk of disqualification?

- Issues with having an Anti-defection law

- Recommendations regarding Anti-Defection law

- Contention regarding the time-limit for Defection decision

What is Defection (Aaya Ram Gaya Ram)?

- ‘Defection’ has been defined as, “To abandon a position or association, often to join an opposing group”.

- Aaya Ram Gaya Ram (English: Ram has come, Ram has gone) expression in politics of India means the frequent floor-crossing, turncoating, switching parties and political horse trading in the legislature by the elected politicians and political parties.

- A legislator is deemed to have defected if he either voluntarily gives up the membership of his party or disobeys the directives of the party leadership on a vote. This implies that a legislator defying (abstaining or voting against) the party whip on any issue can lose his membership of the House.

- The law applies to both Parliament and state assemblies.

- The anti-defection law sought to prevent such political defections which may be due to reward of office or other similar considerations.

10th Schedule of the Indian Constitution (Anti-Defection Law)

- The Tenth Schedule was inserted in the Constitution in 1985 by the 52nd Amendment Act and technically the Tenth Schedule to the Indian Constitution is the anti-defection law in India.

- It is designed to prevent political defections prompted by the lure of office or material benefits or other like considerations.

- It lays down the process by which legislators may be disqualified on grounds of defection by the Presiding Officer of a legislature based on a petition by any other member of the House.

- The law applies to both Parliament and State Assemblies.

When do the Legislators face risk of disqualification?

Disqualification of a legislator (member of the parliament or legislative assemblies) is possible when the member:

- Gives up his membership of a political party voluntarily

- Votes or abstains from voting in the House, contrary to any direction issued by his political party (Party Whip is an official of a political party who acts as the party’s ‘enforcer’ inside the legislative assembly or house of parliament.)

- Joins any party after being elected as independent candidate

- Joins any political party after 6 months of being nominated as a legislative member

The Supreme Court mandated that in the absence of a formal resignation, the giving up of membership can be determined by the conduct of a legislator, such as publicly expressing opposition to their party or support for another party, engaging in anti-party activities, criticizing the party on public forums on multiple occasions, and attending rallies organised by opposition parties.

Exceptions:

- Legislators can change their party without the risk of disqualification to merge with or into another party provided that at least two-thirds of the legislators are in favour of the merger, neither the members who decide to merge, nor the ones who stay with the original party will face disqualification.

- Earlier, the law allowed parties to be split (this used to allow for legislators to hold their position while actually “defecting” to either of the split parties), but at present, this has been outlawed.

- Any person elected as chairman or speaker can resign from his party, and rejoin the party if he demits that post.

Who takes the decision on Defection?

- The decision on disqualification questions on the ground of defection is referred to the Speaker or the Chairman of the House, and his/her decision is final.

- The Presiding Officer has NO time limit to make his decision

- All proceedings in relation to disqualification under this Schedule are considered to be proceedings in Parliament or the Legislature of a state as is the case.

- The law initially stated that the decision of the Presiding Officer is not subject to judicial review. This condition was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1992, thereby allowing appeals against the Presiding Officer’s decision in the High Court and Supreme Court.

- There is no time limit as per the law within which the Presiding Officers should decide on disqualification for defection.

Issues with having an Anti-defection law

- The principle of the Anti-defection law basically forces members vote based on the decisions taken by the party leadership, and not based on what their constituents would like them to vote for – can be considered as a hindrance to the “functioning of the legislature” in the true sense of the word. It limits a legislator from voting according to his/her own conscience, judgement and electorate’s interests.

- The core role of an MP to examine and decide on a policy, bills, and budgets is side-lined. Instead, the MP becomes just another number to be tallied by the party on any vote that it supports or opposes.

- It can also be said that this provision goes against the concept of representative democracy.

- In the parliamentary form, the government is accountable daily through questions and motions and can be removed any time it loses the support of the majority of members of the Lok Sabha. In India, this chain of accountability has been broken by making legislators accountable primarily to the political party. Thus, anti-defection law is acting against the concept of parliamentary democracy.

Recommendations regarding Anti-Defection law

- Dinesh Goswami Committee on electoral reforms recommended that Disqualification should be limited to a member voluntarily gives up the membership of his political party and a member abstains from voting, or votes contrary to the party whip in a motion of vote of confidence or motion of no-confidence.

- The Law Commission in its 170th Report recommended that provisions which exempt splits and mergers from disqualification to be deleted and also Pre-poll electoral fronts should be treated as political parties under anti-defection. It also recommended that Political parties should limit issuance of whips to instances only when the government is in danger.

Contention regarding the time-limit for Defection decision

- There is no time limit as per the law within which the Presiding Officers should decide on a plea for disqualification. The courts also can intervene only after the officer has made a decision, and so the only option for the petitioner is to wait until the decision is made.

- There have been several cases where the Courts have expressed concern about the unnecessary delay in deciding such petitions.

- In a few cases, there have been situations where members who had defected from their political parties continued to be House members, because of the delay in decision-making by the Speaker or Chairman.

- There have also been instances where opposition members have been appointed ministers in the government while still being members of their original political parties in the state legislature.

- The court had urged Parliament to “re-consider strengthening certain aspects of the Tenth Schedule [anti-defection law], so that such undemocratic practices are discouraged”. The Karnataka judgment of 2019 said Speakers who cannot veer away from their constitutional duty to remain neutral do not deserve the chair.

- However, the Supreme Court still holds that it cannot legislate and hence cannot frame guidelines for fixing time limits within which presiding officers should decide defection petitions against legislators.

-Source: The Hindu

Indian schools and access to Internet in 2019-20

Context:

Education Ministry recently released data in the Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) report regarding presence of Internet facilities in schools in India when online education was the need of the hour for education during the pandemic.

Relevance:

GS-II: Social Justice (Issues related to education, Human resources – issues in development & management)

Dimensions of the Article:

- Highlights of the UDISE+ report

- National Statistical Organisation (NSO) survey reports

- Other data regarding Inequality in Online education

Highlights of the UDISE+ report

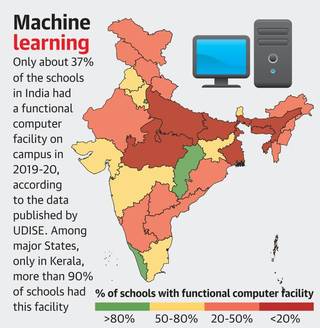

- The Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) report shows that only 22% of schools in India had Internet facilities and among government schools, less than 12% had Internet in 2019-20, while less than 30% had functional computer facilities.

- In many Union Territories, as well as in the State of Kerala, more than 90% of schools, both government and private, had access to working computers.

- In States such as Chhattisgarh (83%) and Jharkhand (73%), installation of computer facilities in most government schools paid off, while in others such as Tamil Nadu (77%), Gujarat (74%) and Maharashtra (71%), private schools had higher levels of computer availability than in government schools.

- However, in States such as Assam (13%), Madhya Pradesh (13%), Bihar (14%), West Bengal (14%), Tripura (15%) and Uttar Pradesh (18%), less than one in five schools had working computers. The situation is worse in government schools, with less than 5% of U.P.’s government schools having the facility.

- The connectivity divide is even starker. Only three States — Kerala (88%), Delhi (86%) and Gujarat (71%) — have Internet facilities in more than half their schools.

National Statistical Organisation (NSO) survey reports

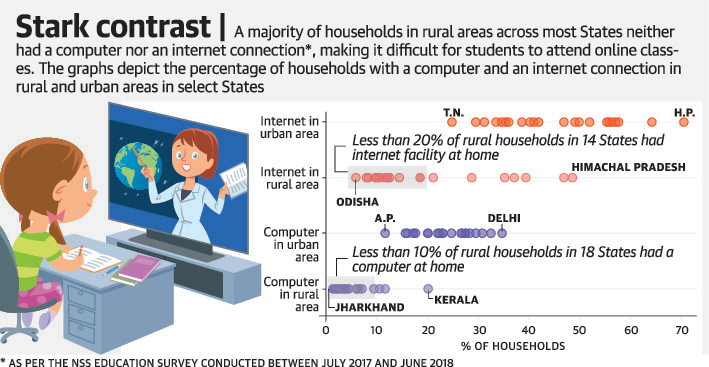

- A recent report on the latest National Statistical Organisation (NSO) survey shows just how stark is the digital divide across States, cities and villages, and income groups.

- Across India, only one in ten households have a computer — whether a desktop, laptop or tablet.

- However, almost a quarter of all homes have Internet facilities, accessed via a fixed or mobile network using any device, including smartphones.

- Most of these Internet-enabled homes are located in cities, where 42% have Internet access.

- In rural India, however, only 15% are connected to the internet.

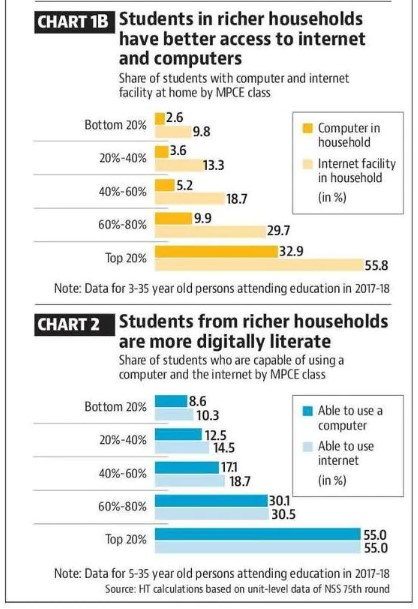

- The biggest divide is by economic status, which the NSO marks by dividing the population into five equal groups, or quintiles, based on their usual monthly per capita expenditure.

How the states fared?

- The national capital has the highest Internet access, with 55% of homes having such facilities.

- Himachal Pradesh and Kerala are the only other States where more than half of all households have Internet.

- At the other end of the spectrum is Odisha, where only one in ten homes have Internet.

- There are ten other States with less than 20% Internet penetration, including States with software hubs such as Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

- Kerala shows the least inequality: more than 39% of the poorest rural homes have Internet, in comparison to 67% of the richest urban homes.

- Assam shows the starkest inequality, with almost 80% of the richest urban homes having the Internet access denied to 94% of those in the poorest rural homes in the State.

Other data regarding Inequality in Online education

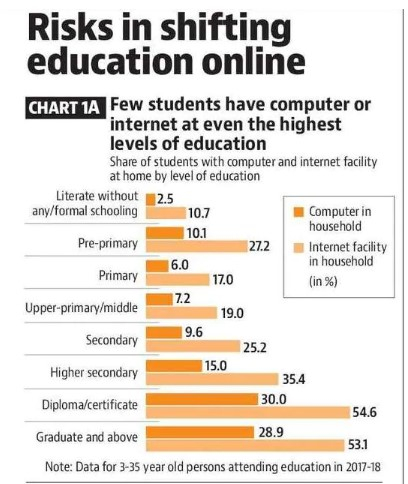

- Three-fourths of students in India did not have access to the internet at home, according to a 2017-18 all-India NSO survey.

- The share of those who did not have computers, including devices such as palm-tops and tablets, was much greater ~90%.

- Access to these facilities was higher among students at higher levels of education. But even at the highest levels, a large share of students did not have access to these facilities. As expected, access to the internet and computers is directly related to household incomes.

- Lack of access to the internet and devices has also created a gap in digital literacy.

- As many as 76% of students in India in the 5-35 age group did not know how to use a computer.

- The share of those who did not know how to use the internet was 74.5%. Once again, this gap rises with a fall in income levels.

- 55% of students among the top 20% of households by monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) knew how to use a computer and internet while these proportions were only 9% and 10% among the bottom 20%.

-Source: The Hindu

WB support to India’s informal working class

Context:

World Bank said it has approved a USD 500 million (about Rs 3,717.28 crore) loan programme to support India’s informal working class to overcome the current pandemic distress.

Relevance:

GS-III: Indian Economy (Inclusive growth, Government Policies and Interventions), GS-II: International Relations (Important International Institutions)

Dimensions of the Article:

- About India’s Informal Workforce

- Issues with having a majority in the informal sector

- About the World Bank’s Financial Support

Click Here to read about the World Bank and World Bank Group

About India’s Informal Workforce

- India’s estimated 450 million informal workers comprise 90% of its total workforce, with 5-10 million workers added annually. (As per Periodic Labour Force Survey, 2017-18, 90.6 per cent of India’s workforce was informally employed.)

- Informal Labour is largely characterized by skills gained outside of a formal education, easy entry, a lack of stable employer-employee relationships, and a small scale of operations.

- The statistics of the ILO report indicates that 95% of the workforce is in the informal sector.

- India’s informal sector is the biggest piece in our economy as it employs the vast majority of the workforce accounting for about half of GNP according to Credit Suisse, and the formal sector depends on its goods and services.

- Between 2004-05 and 2017-18, a period when India witnessed rapid economic growth, the share of the informal workforce witnessed only a marginal decline from 93.2 per cent to 90.6 per cent.

- Looking ahead, it is likely that informal employment will increase as workers who lose formal jobs during the COVID crisis try to find or create work (by resorting to self-employment) in the informal economy.

- Further, according to Oxfam’s latest global report, out of the total 122 million who lost their jobs in 2020, 75% were lost in the informal sector.

Issues with having a majority in the informal sector

- The informal sector remains unmonitored by the government.

- No official statistics are available representing the true state of the informal sector in particular (and hence the economy as a whole) which makes it difficult for the government to make policies. Unlike the formal economy, the informal sector’s components are not included in GDP computations.

- Informal sector workers have no job security, minimal benefits, very low pay, and often face hazardous working conditions.

- There is an expectation of increase in the number of people in informal sector with the issue that about 65-75% (15 million) of Indian youth, that enter the workforce each year are not job-ready or suitably employable.

- In India Restrictive labour laws- which promotes ad hocism and contract hiring in the labour market to circumvent the rigid labour laws.

About the World Bank’s Financial Support

- Of the USD 500 million commitment, USD 112.50 million will be financed by its concessionary lending arm International Development Association (IDA) and the rest will be a loan from International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD).

- States can now access flexible funding from disaster response funds to design and implement appropriate social protection responses.

- The funds will be utilised in social protection programmes for urban informal workers, gig-workers, and migrants.

- Investments at the municipal level will promote National Digital Urban Mission that will create a shared digital infrastructure for people living in urban areas and will scale up urban safety nets and social insurance for informal workers.

- The programme will give street vendors access to affordable working capital loans of up to Rs 10,000.

-Source: Indian Express

ITU’s Global Cybersecurity Index

Context:

Recently, the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) 2020 was released by International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and it ranked India among the top 10 countries.

Relevance:

GS-III: Internal Security Challenges (Cybersecurity, Cyber warfare, Challenges to Internal Security Through Communication Networks)

Dimensions of the Article:

- The Need, Challenges and Measures regarding Cyber Security in India

- About the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) and ITU

- Highlights of the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI)

- About India’s Progress on cyberspace security

Click Here to read about the Need, Challenges and Measures regarding Cyber Security in India

About the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) and ITU

- The Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI) assessment is done on the basis of performance on five parameters of cybersecurity including legal measures, technical measures, organisational measures, capacity development, and cooperation.

- The GCI is released by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU).

- The International Telecommunication Union is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for all matters related to information and communication technologies.

- The ITU promotes the shared global use of the radio spectrum, facilitates international cooperation in assigning satellite orbits, assists in developing and coordinating worldwide technical standards, and works to improve telecommunication infrastructure in the developing world.

- It is also active in the areas of broadband Internet, wireless technologies, aeronautical and maritime navigation, radio astronomy, satellite-based meteorology, TV broadcasting, and next-generation networks.

- The ITU was initially aimed at helping connect telegraphic networks between countries. However, with its mandate consistently broadening with the advent of new communications technologies – it adopted its current name in 1934.

Highlights of the Global Cybersecurity Index (GCI)

- The US topped the rankings on key cybersafety parameters and was placed above the UK (United Kingdom) and Saudi Arabia tied on the second position together. Following these 3 countries, Estonia was ranked third (3rd) in the index.

- India has been ranked tenth (10th) and has moved up 37 places. India has also secured the fourth position in the Asia Pacific region, underlining its commitment to cybersecurity.

- The GCI results for India show substantial overall improvement and strengthening under all parameters of the cybersecurity domain.

- India scored a total of 97.5 points from a possible maximum of 100 points, to make it to the tenth position worldwide in the GCI 2020.

About India’s Progress on cyberspace security

- India has made only “modest progress” in developing its policy and doctrine for cyberspace security despite the geo-strategic instability of its region and a keen awareness of the cyber threat it faces.

- The military confrontation with China in the disputed Ladakh border area in June 2020, followed by a sharp increase in Chinese activity against Indian networks, has heightened Indian concerns about cyber security, not least in systems supplied by China.

- India has some cyber-intelligence and offensive cyber capabilities but they are regionally focused, principally on Pakistan.

- India’s approach towards institutional reform of cyber governance has been “slow and incremental”, with key coordinating authorities for cyber security in the civil and military domains established only as late as 2018 and 2019 respectively.

- The strengths of the Indian digital economy include a vibrant start-up culture and a very large talent pool. The private sector has moved more quickly than the government in promoting national cyber security.

- The country is active and visible in cyber diplomacy but has not been among the leaders on global norms, preferring instead to make productive practical arrangements with key states. India is currently aiming to compensate for its weaknesses by building new capability with the help of key international partners – including the US, the UK and France – and by looking to concerted international action to develop norms of restraint.

-Source: Hindustan Times, Indian Express

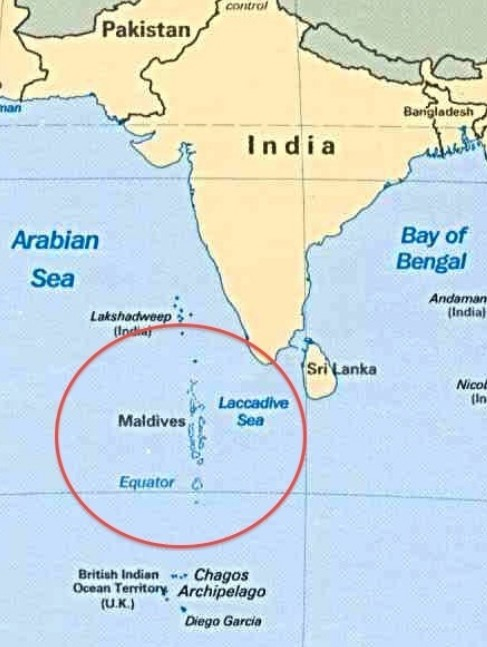

India to Maldives on attacks in media

Context:

India has sought Maldivian government action on persons behind media reports and social media posts “attacking the dignity” of its resident diplomats, while seeking greater security for the officials.

Relevance:

GS-II: International Relations (India’s Neighbors, Foreign Policies affecting India’s Interests)

Dimensions of the Article:

- About India’s message to Maldives on Media Attacks

- India–Maldives relations

- Cooperation Between India & Maldives

- Irritants in India – Maldives relations

About India’s message to Maldives on Media Attacks

- In a letter the High Commission of India said the “repeated attacks” were “motivated, malicious and increasingly personal” against India’s resident diplomats.

- India urged the Maldives Foreign Ministry to take steps to “ensure enhanced protection” of the Indian Mission and its officials and to “ensure action, in accordance with International Law and Maldivian Law” against the perpetrators for “these gross violations” of the Vienna Convention of Diplomatic Relations.

- While India-Maldives ties came under considerable strain during former Maldives President’s term, the current President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s government is seen to be a close ally of India, with enhanced development and defence cooperation since 2018.

- However, some government critics in the Maldives are wary of greater military ties with India that they see as paving way for “boots on the ground”.

- In 2021, an announcement made in New Delhi, on the Cabinet clearing a proposal to set up a second mission in the Indian Ocean Archipelago, sparked concern among sections, prompting a renewed “#Indiaout” campaign on Maldivian social media.

India–Maldives relations

- India and Maldives are neighbors sharing a maritime border and relations between the two countries have been friendly and close in strategic, economic and military cooperation.

- Maldives is located south of India’s Lakshadweep Islands in the Indian Ocean.

- Both nations established diplomatic relations after the independence of Maldives from British rule in 1966.

- India has supported Maldives’ policy of keeping regional issues and struggles away from itself, and the latter has seen friendship with India as a source of aid as well as a counterbalance to Sri Lanka, which is in proximity to the island nation and its largest trading partner.

Cooperation Between India & Maldives

- Through the decades, India has rushed emergency assistance to the Maldives, whenever sought.

- In 1988, when armed mercenaries attempted a coup against President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom, India sent paratroopers and Navy vessels and restored the legitimate leadership under Operation Cactus.

- Further, joint naval exercises have been conducted in the Indian ocean and India still contributes to the security of the maritime island.

- The 2004 tsunami and the drinking water crisis in Male a decade later were other occasions when India rushed assistance.

- At the peak of the continuing COVID-19 disruption, the Maldives has been the biggest beneficiary of the Covid-19 assistance given by India among its all of India’s neighbouring countries.

- When the world supply chains were blocked because of the pandemic, India continued to provide crucial commodities to the Maldives under Mission SAGAR.

- Recently, in 2021, India extended its support to the Maldives’ Foreign Minister at the election for the President of the General Assembly (PGA) in the United Nations.

Irritants in India – Maldives relations

- In the past decade or so, the number of Maldivians drawn towards terrorist groups like the Islamic State (IS) and Pakistan-based madrassas and jihadist groups has been increasing. Political instability and socio-economic uncertainty are the main drivers fuelling the rise of Islamist radicalism in the island nation.

- China’s strategic footprint in Maldives and the rest of India’s neighbourhood has increased. The Maldives has emerged as an important ‘pearl’ in China’s “String of Pearls” construct in South Asia.

- One of India’s major concerns has been the impact of political instability in the neighbourhood on its security and development. The February 2015 arrest of opposition leader Mohamed Nasheed on terrorism charges and the consequent political crisis have posed a real diplomatic test for India’s neighbourhood policy.

-Source: The Hindu