Context:

India’s reservation system has played a critical role in offering access to opportunities for historically marginalized groups, particularly Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). However, ongoing debates have raised questions about the equitable distribution of these benefits among various SC subgroups. In response, the Supreme Court has suggested a “quota-within-quota” approach to tackle these disparities. This proposal has sparked a nationwide discussion, focusing on whether data justifies such redistributive measures to ensure fairness within the reservation system.

Relevance:

GS II: Polity and Governance

Dimensions of the Article:

- About caste quota

- Data from Different States:

- Are reservations accessible?

- Assessing the ‘Quota-Within-Quota’ Approach to Affirmative Action

- The ‘quota-within-quota’ concept involves subdividing existing reservat

- Conclusion

About caste quota

- Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the principal architect of the Indian Constitution, believed that formal legal equality (one person, one vote) would not be enough to dismantle the deeply entrenched inequalities of caste.

- Thus, reservations were mandated to become a mechanism to move from legal equality to substantive equality by creating opportunities for SCs and STs in higher education, public sector jobs, and government institutions.

- The argument underlying the Supreme Court verdict is that despite its progressive aims, India’s reservation system is plagued by uneven outcomes.

- Some SC groups seem to have progressed more than others over the decades. This has led to calls for a more nuanced approach to affirmative action — one that recognises the heterogeneity within the SC category itself.

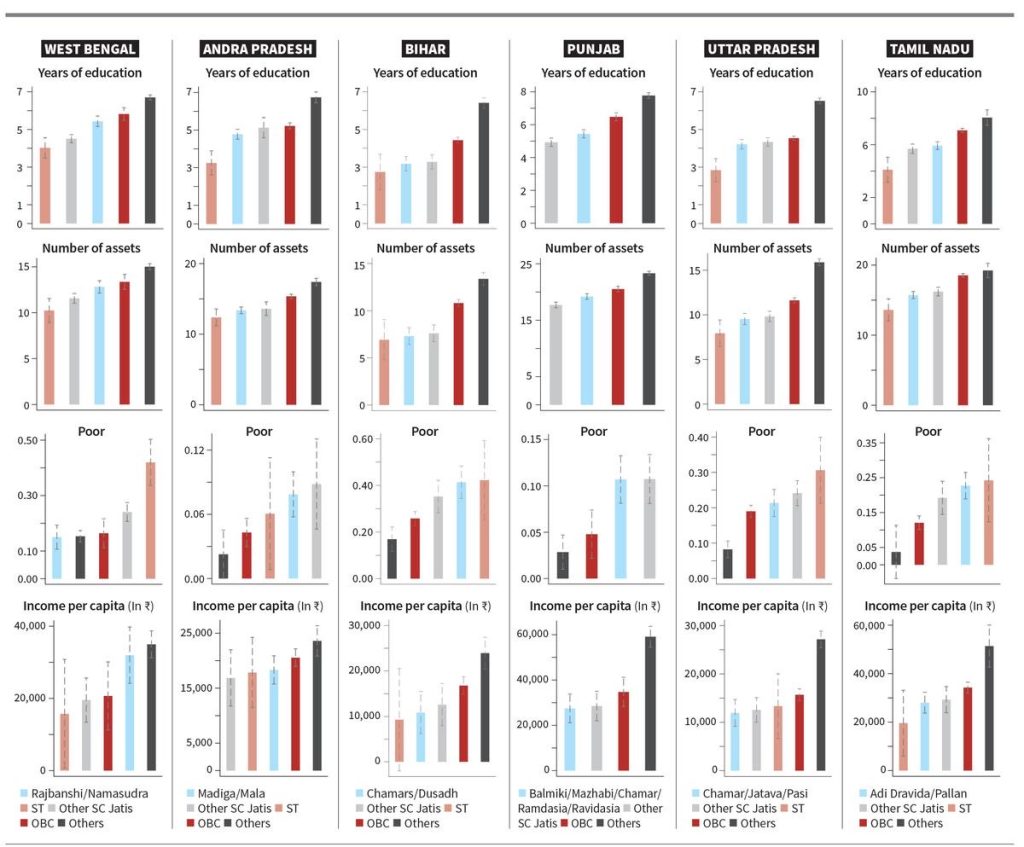

Data from Different States:

Andhra Pradesh

- Our estimates reveal that while there are slight differences between the two major SC groups — Malas and Madigas — the disparities are not significant enough to warrant subdivision of the quota. By 2019, both groups had seen improvements in education and employment, and both were equally likely to benefit from white-collar jobs.

Tamil Nadu

- The two largest SC groups — Adi Dravida and Pallan —were almost indistinguishable in terms of socio-economic outcomes by 2019. But other States paint a more complicated picture.

Punjab

- SC quota has been subdivided since 1975, the data suggests that this policy has led to better outcomes for more disadvantaged SC groups, such as the Mazhabi Sikhs and Balmikis. These groups, once marginalised even within the SC category, have begun to catch up to more advanced groups such as the Ad Dharmis and Ravidasis.

Bihar

- Subdividing the SC quota into a “Mahadalit” category in 2007 is a cautionary tale. Initially designed to target the most marginalised SC groups, the policy eventually faltered as political pressure led to the inclusion of all SC groups in the Mahadalit category, effectively nullifying the purpose of the subdivision.

The broader takeaway from these findings is that while there is some heterogeneity within the SC category, the disparities between SC groups and upper-caste groups (general category) remain far more pronounced. In other words, the gap between SCs and the privileged castes is still much larger than the gap between different SC subgroups.

Are reservations accessible?

- We need good jati-wise data on actual use of reserved category positions. The closest we can get is based on a question from the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) that asks potential beneficiaries if they have a caste certificate — a prerequisite for accessing reserved positions in education and employment.

- These numbers can be seen as proxy for actual access in the absence of authoritative official data.

- In States like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, less than 50% of SC households report having these certificates, meaning that a large portion of SCs are excluded from the benefits that are supposed to uplift them.

- Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh fare better, with over 60-70% of SC households holding caste certificates, but these States are the exception rather than the rule.

- This highlights a fundamental problem with the current system — access. Without ensuring that all eligible SCs can actually benefit from reservations, subdividing the quota becomes a secondary concern.

- The focus should first be on improving access to reservations across the board, ensuring that those who are entitled to these benefits can avail them.

Assessing the ‘Quota-Within-Quota’ Approach to Affirmative Action

The ‘quota-within-quota’ concept involves subdividing existing reservations among subgroups within Scheduled Castes (SCs) and other marginalized communities. This idea has yielded mixed results across various states in India, showing potential in some areas while raising concerns in others.

Regional Variations and Efficacy

- Localized Success: In states like Punjab, where disparities among SC subgroups are pronounced, subdividing quotas has proven beneficial, bringing more marginalized groups into mainstream opportunities.

- Unnecessary Complications: Conversely, in states like Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, the data indicate that the benefits of reservations are already equitably distributed among SC groups, making further subdivisions redundant.

Political Dynamics and Policy Impact

- Political Exploitation: The experience in Bihar suggests that political motives can compromise the integrity of affirmative action. Policy decisions based on political gain rather than factual analysis can weaken the impact of reservations, reducing them to mere tools of political leverage rather than means of genuine social advancement.

Judicial Perspectives and Creamy Layer Concept

- Supreme Court’s Stance: The proposal to introduce a ‘creamy layer’ criterion for SCs, akin to that applied to Other Backward Classes (OBCs), lacks sufficient empirical support at present. This approach necessitates a careful review of how socio-economic advancements influence discrimination against historically marginalized groups.

Economic Factors and Reservation Benefits

- Financial Assistance: While quotas address representational disparities, monetary benefits like scholarships and lower fees should focus on need-based criteria to ensure that support reaches the most economically disadvantaged individuals.

Persistence of Stigma Despite Economic Gains

- Societal Bias: Advancements in economic status do not necessarily eradicate the deep-seated stigmatization faced by SCs. Instances of untouchability, though legally abolished, continue covertly and overtly, underscoring the enduring impact of social identity on discrimination.

The Need for Updated Data

- Data Deficiency: The lack of current and comprehensive data on caste-based disparities — exacerbated by delays in conducting the national Census — hampers effective policy formulation and reform. Accurate data is crucial for tailoring affirmative action policies that genuinely reflect and address the needs of marginalized populations.

Conclusion

While the idea of a ‘quota-within-quota’ has potential in specific regional contexts, its overall effectiveness is contingent on nuanced implementation that is sensitive to the varying needs and conditions of SC subgroups across different states. For affirmative action to fulfill its role as a catalyst for social justice, it must be underpinned by reliable data and implemented free from political manipulation. The journey towards eliminating caste-based disparities is ongoing, and policies must evolve based on robust evidence and an unwavering commitment to equity.

-Source: The Hindu