CONTENTS

- Remoulding the Global Plastics Treaty

- The Centre is Notional, the States are the Real Entities

Remoulding the Global Plastics Treaty

Context:

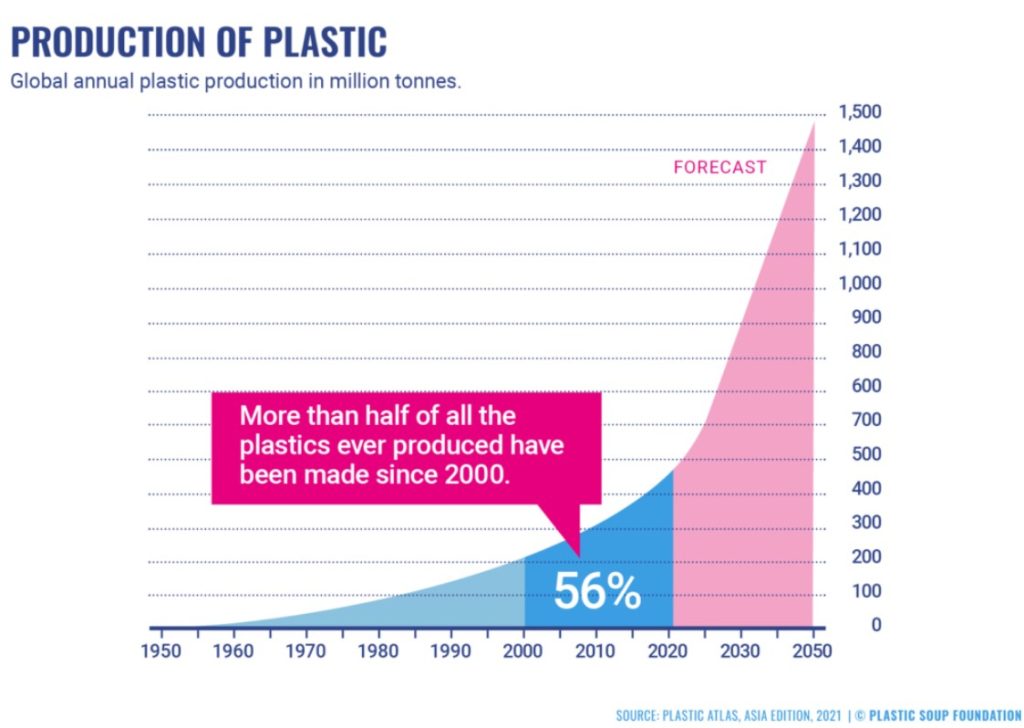

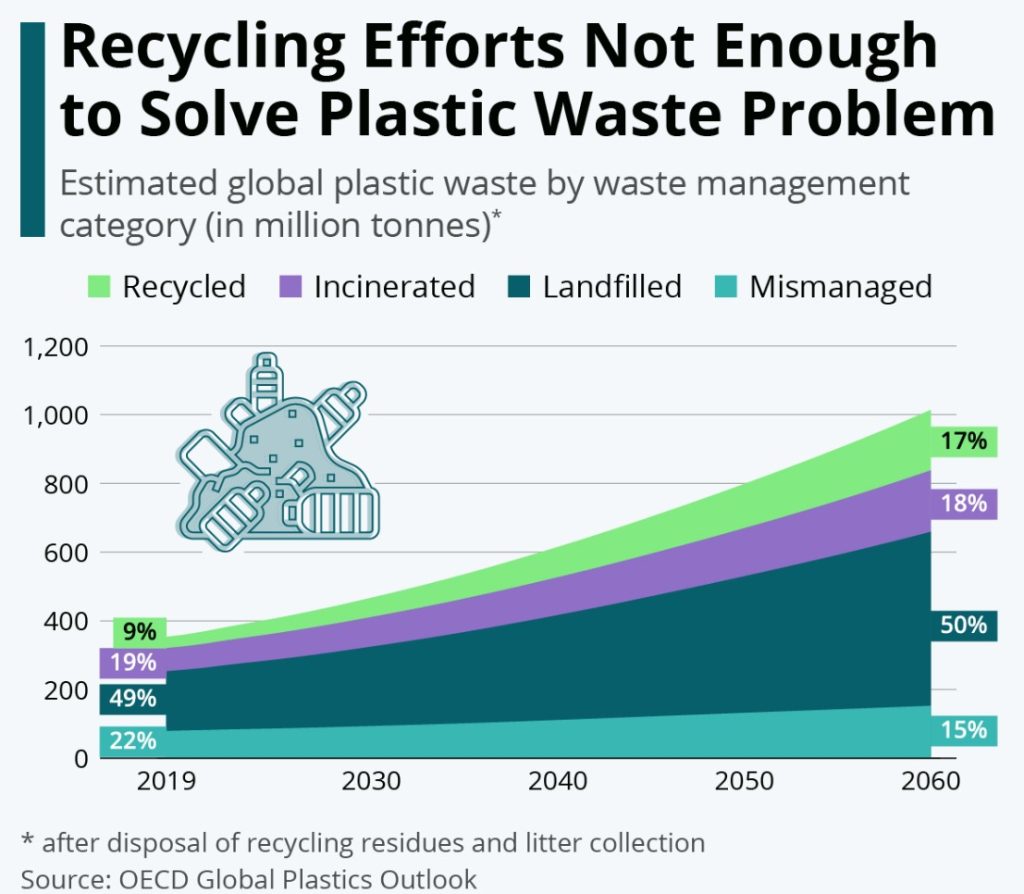

As discussions continue regarding an international legally binding treaty on plastic pollution, it’s crucial to consider how it can support a fair transition for individuals who informally collect and recycle waste. According to the OECD Global Plastic Outlook, global plastic waste production reached 353 million tonnes in 2019, more than double the amount in 2000, and is projected to triple by 2060.

Relevance:

GS3- Environmental Pollution and Degradation

Mains Question:

In the context of the Global Plastic Treaty as an instrument to end plastic pollution, discuss the significance it holds in ensuring social justice and equity principles for the informal recycling worker. (10 Marks, 150 Words).

Recycling of the Plastic Waste:

- Only 9% of this waste was recycled, with 50% sent to landfills, 19% incinerated, and 22% disposed of in uncontrolled sites or dumps.

- The United Nations Environment Programme notes that 85% of the recycled plastic was processed by informal recycling workers.

- These workers collect, sort, and recover recyclable and reusable materials from general waste, alleviating municipal budgets of financial burdens related to waste management.

- They significantly subsidize the environmental mandates of producers, consumers, and the government.

- The Centre for Environment Justice and Development has also observed that these workers promote circular waste management solutions and help mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, contributing valuably to sustainability.

- Their efforts significantly reduce the plastic content in landfills and dump sites, effectively preventing plastic from leaking into the environment.

The Need for Recognition:

- Despite their crucial role, informal waste collectors often go unrecognized and remain highly vulnerable within plastic value chains.

- They face threats from the increasing privatization of waste management, the rise of waste-to-energy or incineration projects, and exclusion due to public policy interventions in plastic waste management, particularly under Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) norms.

- The informal waste and recovery sector (IWRS) is a significant component of global municipal solid waste management systems.

- According to the UN-Habitat’s Waste Wise Cities Tool (WaCT), the informal sector is responsible for 80% of municipal solid waste recovery in many cities.

- A recent study by UN-Habitat and the University of Leeds estimates that around 60 million tonnes of plastic from municipal solid waste end up polluting the environment, including water bodies, due to inadequate collection services and mismanagement of solid waste. Without the IWRS, this volume would be even higher.

- However, the recent “Leave No One Behind” report highlights that strategies to reduce plastic pollution often fail to effectively engage the recovery capacities, skills, and knowledge of the IWRS.

- This oversight increases the livelihood vulnerabilities of informal workers and undermines existing informal recovery systems.

Global Treaty and the Need for a Just Transition:

- The Global Plastics Treaty represents a significant effort to create a legally binding agreement aimed at reducing and eliminating plastic pollution.

- The decision to form an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) was made during the fifth UN Environment Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya, in early 2021.

- The INC’s journey began with an Ad Hoc Open-Ended Working Group meeting in Dakar, Senegal, in mid-2022, followed by subsequent meetings in Uruguay, Paris, and Nairobi, culminating in the fourth INC-4 meeting in Canada in April this year.

- The final INC-5 meeting in South Korea will see active participation from the International Alliance of Waste Pickers (IAWP).

- The IAWP, a vocal participant in the UNEA Plastic Treaty process, stresses the importance of supporting the formalization and integration of informal waste pickers into discussions on addressing plastics.

- It advocates for including waste pickers’ perspectives and solutions at every stage of policy and law implementation.

- These measures aim to recognize waste pickers’ historical contributions, protect their rights, and promote effective and sustainable plastic waste management practices.

- However, there is no universally agreed-upon terminology for a just transition or a formal definition of the informal waste sector and its workforce. Clarifying these definitions is crucial.

India’s Voice is Important:

- As a key representative from the Global South, India advocates for an approach that enhances repair, reuse, refill, and recycling without completely eliminating the use of plastics.

- India also emphasizes the importance of considering country-specific circumstances and capacities. Consequently, India’s informal waste pickers, who are essential, remain central to the discussion.

- We need to reconsider our formulation of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) norms and explore how to integrate this informal worker cohort into the new legal framework.

Conclusion:

As the final round of negotiations for the Global Plastics Treaty approaches at INC-5, a crucial question remains: how can a global instrument to end plastic pollution enable a just transition for nearly 15 million people who informally collect and recover up to 58% of global recycled waste, thereby shaping a sustainable future? By incorporating their perspectives and ensuring their livelihoods are protected, the treaty can embody principles of social justice and equity, leaving no one and no place behind.

The Centre is Notional, the States are the Real Entities

Context:

The results of the 2024 general election have been surprising, indicating a move towards greater democratization in the country as regional parties have performed well. These parties will share seats both on the ruling party benches and in the Opposition in Parliament, which will help strengthen federalism—a crucial aspect for a diverse nation like India, which had been weakening recently.

Relevance:

GS2-

- Federalism

- Co-operative Federalism

- Centre-State Relations

- Inter-State Relations

Mains Question:

Utilisation of the country’s resources needs to be decided jointly by the Centre and the States. Discuss whether the changed political situation after the general election makes this feasible or raises more doubts. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

The 2024 General Election:

- Centre-State relations became contentious during the 2024 election campaign. Ideas such as ‘400 paar’ (aiming for 400 seats), ‘one nation, one election,’ and the Prime Minister’s strong warning that corrupt leaders (implying Opposition leaders) would soon be jailed were perceived as threats to Opposition-ruled States.

- Opposition-ruled States have been voicing complaints about unfair treatment by the Centre, leading to protests in Delhi and State capitals.

- The Supreme Court of India has noted a steady stream of States being compelled to approach it against the Centre.

- Kerala has complained about insufficient resource transfers, Karnataka about drought relief, and West Bengal about funds for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS).

- The Supreme Court, expressing its helplessness, recently stated that Centre-State issues need to be resolved amicably.

- When the ruling party came to power in 2014, it spoke of cooperative federalism. The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017 exemplified this cooperative spirit, as States with reservations eventually agreed to its implementation.

- However, that was the last significant instance of such cooperation. With federalism weakening, discord between the Centre and Opposition-ruled States has increased.

- India’s States are incredibly diverse—Assam is different from Gujarat, and Himachal Pradesh varies greatly from Tamil Nadu. A one-size-fits-all approach is not conducive to the progress of such diverse States.

- They need greater autonomy to address their unique issues, which is essential for both democracy and federalism.

- A dominant Centre imposing its will on the States, leading to deteriorating Centre-State relations, is not beneficial for India.

Financing and Conflict:

- States face three broad categories of issues. Some, like education, health, and social services, can be managed by each State independently without affecting others.

- However, infrastructure and water sharing require inter-state agreements.

- Issues such as currency and defense necessitate a unified approach, needing higher authority from the Centre to ensure coordination and optimal outcomes.

- Financing expenditures to achieve goals often leads to conflict. Revenue must be raised through taxes, non-tax sources, and borrowings. The Centre plays a dominant role in resource collection due to the efficiency of centralized tax collection.

- Major taxes like personal income tax (PIT), corporation tax, customs duty, and excise duty are collected by the Centre. GST is collected by both the Centre and the States and then shared.

- Thus, the Centre controls most of the resources, which must be devolved to the States to enable them to fulfill their responsibilities.

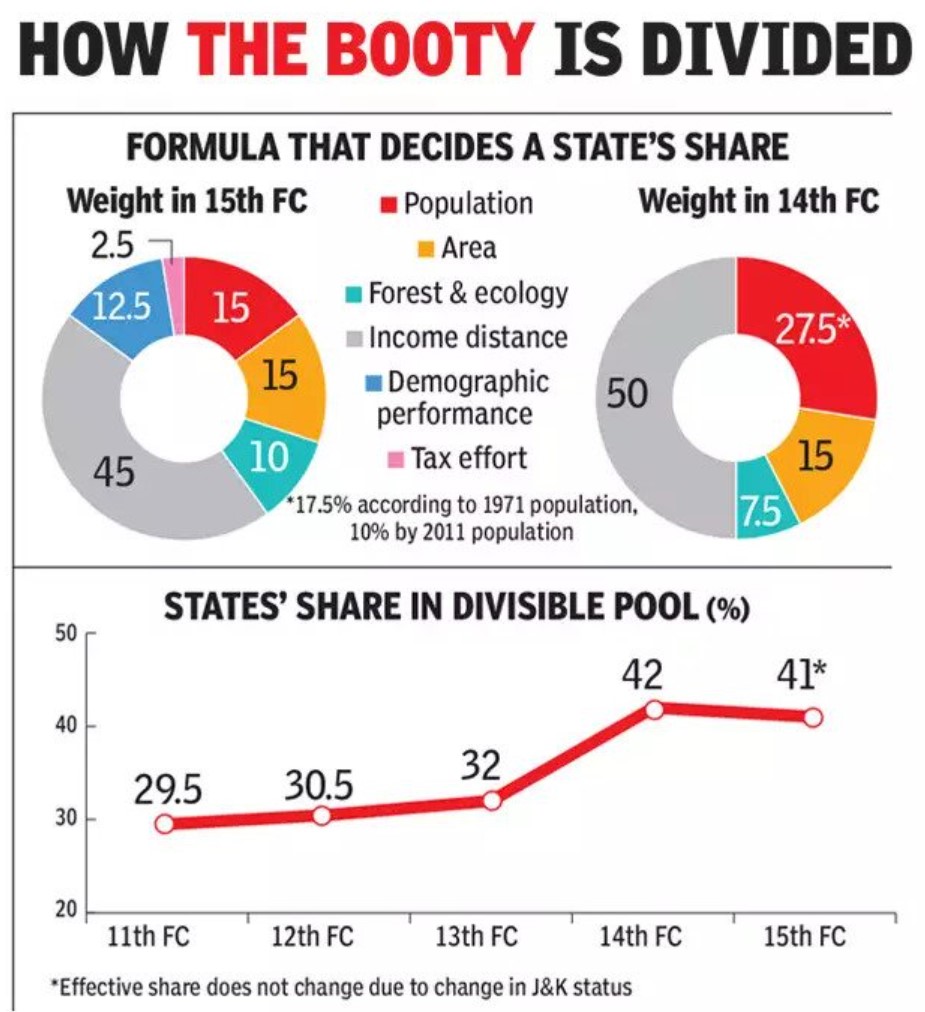

- A Finance Commission is appointed to decide on the devolution of funds from the Centre to the States and the share each State receives.

- The Centre sets up the Commission and mostly sets its terms of reference, introducing a bias in favor of the Centre and becoming a source of conflict between the Centre and the States.

- Additionally, there is an implicit bias in the Commissions that the States are not fiscally responsible, reflecting the Centre’s perspective that States are not managing their finances properly and make undue demands on the Centre.

- States, in turn, tend to pitch their demands high to secure a larger share of the revenues, often showing lower revenue collection and higher expenditures in hopes of a greater allocation from the Commission. Thus, the Commission acts as an arbiter, with the States as supplicants.

Inter-State Tussles and Centre-State Relations:

- States cannot have a common position because they are at different stages of development and have vastly different resource positions. Richer states have more resources, while poorer ones need more to develop faster and catch up.

- The Finance Commission is supposed to allocate proportionately more funds to poorer states, but despite the efforts of 15 Finance Commissions so far, the gap remains wide.

- Richer states, which contribute more and receive proportionately less, have resented this. They often overlook that poorer states provide the market enabling richer states to grow faster.

- Poorer states also lose much of their savings to richer states, accelerating the latter’s development. It’s often argued that since Mumbai contributes a significant portion of corporation and income taxes, it should receive more funds.

- However, this is because Mumbai is the financial capital, where big corporations are based and pay their taxes, not necessarily because production happens there.

- The Centre allocates resources to the states in two ways: through the Finance Commission award and by spending on various projects in the states.

- The latter leads to jobs and prosperity in a state, becoming another source of conflict as each state desires more expenditure within its territory.

- The Centre can play politics in the allocation of schemes and projects, often being accused of favoring certain states like Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh, while Opposition-ruled states complain of step-motherly treatment.

- To secure more resources, states often have to align with the Centre’s directives. This has evolved into the concept of a ‘double engine ki sarkar,’ where the same political party governs both the Centre and the states.

- This suggests that Opposition-ruled states will be at a disadvantage, undermining state autonomy and weakening federalism.

- However, state autonomy should not be confused with complete freedom; it must operate within a national framework for the broader good, balancing common interests with the diverse needs of different states.

Issues in Federalism:

- The Sixteenth Finance Commission has begun its work and should aim to reverse the trend of weakening federalism and strengthen the spirit of India as a ‘Union of States.’ This task is both political and economic.

- The Commission could recommend even-handed treatment of all states by the Centre and reduce friction between rich and poor states by transferring proportionately more resources to poorer states to curb rising inequality.

- Governance issues at both the Centre and state levels need to be addressed, as they impact investment productivity and development pace. Corruption and cronyism lead to resource wastage and a loss of social welfare.

- To reduce the Centre’s dominance over the states, the devolution of resources from the Centre to the states could be increased substantially from the current 41%.

- The Centre’s role could be limited. For instance, joint schemes like the Public Distribution System or MGNREGS often see the Centre insisting on credit, penalizing states that do not comply.

- The Centre’s undue assertiveness undermines federalism. Funds with the Centre are public funds collected from the states and spent in the states.

Conclusion:

The Centre is a notional and constitutionally created entity, while states and local bodies are the real entities where economic activity occurs and resources are generated. States have accepted the Centre’s constitutional position, but this should not make them supplicants for their own funds. It is time for the utilization of the country’s resources to be jointly decided by the Centre and the states as equal partners. This joint decision-making has become more feasible with the changed political landscape following the 2024 general election results.