Context:

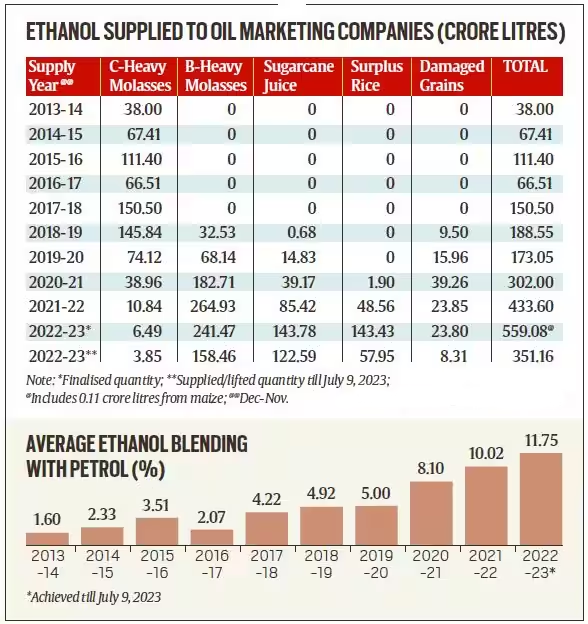

As COP28 in Dubai saw the commitment of over 100 countries to triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030, India is confronted with a delicate situation concerning its ethanol blending objective. Despite the rise in ethanol blended petrol (EBP) from 1.6% in 2013-14 to 11.8% in 2022-23, the 20% target by 2025 faces hurdles due to low sugar stocks in 2022-23 and an anticipated shortfall in sugarcane production this year.

Relevance:

GS-3

- Growth & Development

- Environmental Pollution & Degradation

Mains Question:

The future of India’s renewables strategy hangs on a delicate food-fuel trade-off; and a choice between intensifying hunger and reducing fossil fuel use. Analyse in the context of India’s ethanol blending objectives. (15 Marks, 250 Words).

Ethanol:

- Ethanol, or ethyl alcohol, serves as a biofuel derived from diverse sources like sugarcane, corn, rice, wheat, and biomass. The manufacturing process includes fermenting sugars using yeasts or employing petrochemical methods like ethylene hydration.

- The resulting ethanol is highly pure, reaching 99.9% alcohol content, and it can be combined with gasoline to generate a more environmentally friendly fuel option.

- In addition to its role as a fuel enhancer, ethanol production generates valuable byproducts such as Distillers’ Dried Grain with Solubles and Potash from Incineration Boiler Ash, which find applications in various industries.

- The Ethanol Blending Programme (EBP) is designed to decrease the nation’s reliance on imported crude oil, diminish carbon emissions, and enhance farmers’ earnings.

- The Indian government has expedited the goal for achieving a 20% ethanol blending in petrol, referred to as E20, moving the target year from 2030 to 2025.

Recent Developments:

The recent authorization for the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) and the National Cooperative Consumers’ Federation of India (NCCF) to procure maize (corn) for ethanol distilleries underscores the emphasis on this transition, promoting an organized maize-feed supply chain for ethanol.

However, this transition poses potential challenges for the economy as highlighted below:

Crude and Food Prices:

Crude Oil and Ethanol Production:

- Crude oil and food costs play a pivotal role in the production of ethanol. The primary raw materials for ethanol production are sugarcane in Brazil and corn in the United States.

- The ethanol production in both these nations experienced significant growth from the year 2000 onwards, coinciding with the escalation of crude oil prices, which remained consistently high for a decade. (During periods of low crude oil prices, ethanol blending loses its competitiveness, and its progression is sluggish, often reliant on substantial subsidies.)

Food Prices and Ethanol Production:

- An essential distinction between using sugarcane and corn for ethanol production lies in the extent of the food-fuel conflict that arises.

- In the case of sugarcane, ethanol is generated by processing molasses (C-heavy/B-heavy) and involves minimal trade-offs with sugar production. The path involving B-heavy molasses results in a lower sugar yield compared to the C-heavy path, but both pathways simultaneously generate sugar and ethanol from sugarcane.

- However, utilizing corn for direct ethanol production diminishes its availability for food or livestock feed. This not only redirects grains for fuel purposes but also establishes a direct link between food prices and crude oil prices through demand.

- The prolonged period of exceptionally high crude oil prices from 2004 to 2014 elevated ethanol and corn prices to historic peaks. Significantly, the surge in corn prices quickly affected other grain markets, with soft grains like wheat and barley being redirected to the livestock industry as substitutes for corn.

- Despite only 5-7% of the world’s corn output being used for ethanol production at the peak of the U.S.’s corn-based ethanol program, the price impact was widespread and played a crucial role in the global food crisis from 2006 to 2014. This was primarily attributed to the relative ease of substituting grains across food, feed, and fuel sectors.

- In tropical countries like Brazil or India, unlike in the United States, sugarcane stands out as the more evident choice, given the higher yields it provides.

- It’s important to note, however, that utilizing sugarcane for ethanol production is not without its environmental and hunger-related consequences.

- Expanding the acreage dedicated to water-intensive sugarcane cultivation can displace food production and lead to the degradation of water tables.

- However, these issues can be addressed through effective land-use policies. Controlling market dynamics, influenced by the easily interchangeable use of grains, poses a more challenging task, as exemplified by the United States’ experience with corn-based ethanol.

Meeting the Target:

- In India, the introduction of differential pricing in 2017-18 aimed at encouraging the direct use of cane juice for ethanol production intensified the dilemma between food and fuel, a concern that is typically less pronounced in the context of cane-based ethanol.

- By offering price incentives for ethanol derived from cane juice without sugar extraction— a process yielding significantly more ethanol— mills shifted away from the more sustainable molasses route.

- This decision was driven by the desire to expedite progress toward the 2025 Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) target, which was successfully achieved. However, this success posed challenges in the form of diminished sugar stocks.

- The corrective step taken by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs on December 7, 2023, prohibiting the use of cane juice for ethanol production, is a timely intervention.

- Nevertheless, the government’s shift towards grain-based ethanol, especially with maize expected to contribute around half of the ethanol feed in 2023-24 and beyond, raises concerns about the potential for uncontrollable food inflation.

- To meet the 2025 EBP target, India would require 16.5 million tonnes of grains annually, according to government estimates. This quantity is significant enough to potentially trigger a short-term surge in grain market prices.

Conclusion:

The success of India’s renewable energy strategy hinges on a careful balance between the trade-off of food and fuel, presenting a dilemma between exacerbating hunger and diminishing reliance on fossil fuels. One option for the government is to reevaluate and potentially stagger its Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) target to mitigate these contradictions. There is a need for increased investment in public infrastructure and urban planning to manage automobile fuel demand, alongside a greater emphasis on renewable sources like solar power.