Contents

- National migrant policy: A good first draft

- European Union’s climate change plan work

- SC rejects plea to stall deportation of Rohingyas

- SC on appointment of Ad Hoc judges

NATIONAL MIGRANT POLICY: A GOOD FIRST DRAFT

Context:

The news of the new draft National Migrant Policy being framed by NITI Aayog is an extremely welcome development and the need for this policy is precipitated by the enormous suffering endured by the country’s Circular Migrants (those who migrate short term primarily to earn and remit money back home) during the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in 2020.

Relevance:

GS-II: Social Justice (Issues relating to the development and management of Social Sector/Services, Issues relating to poverty, hunger and Unemployment, Government Policies and Interventions, Issues arising out of design and implementation of policies)

Dimensions of the Article:

- Migrants in India

- Causes of internal migration in India

- About the National Migrant Policy being framed by NITI Aayog

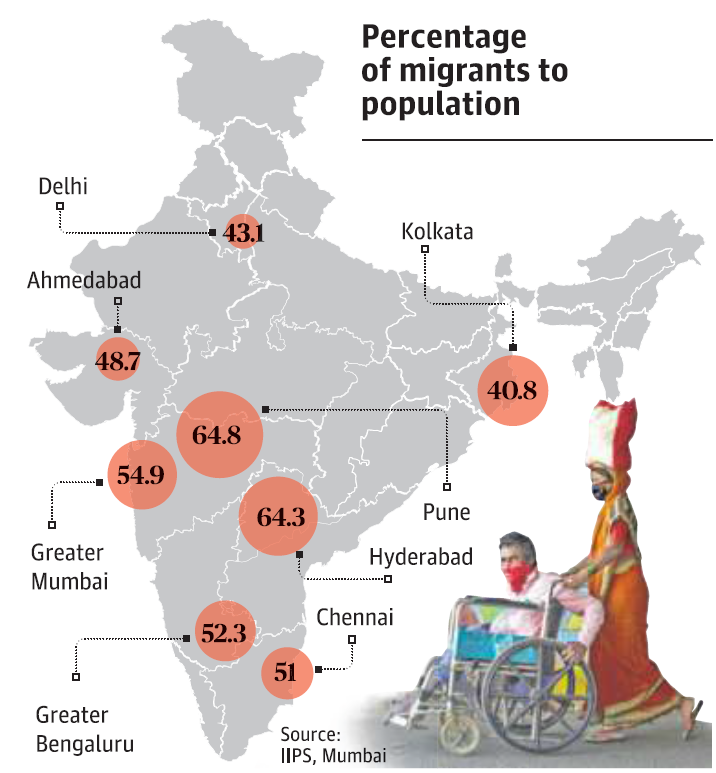

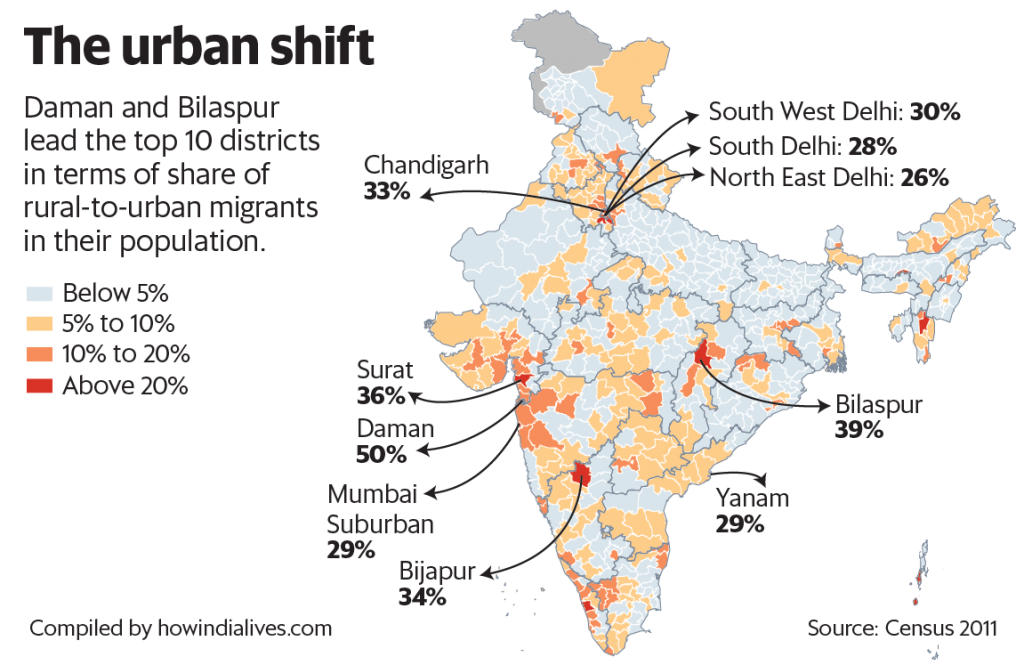

Migrants in India

- The Census defines a migrant as a person residing in a place other than his/her place of birth (Place of Birth definition) or one who has changed his/ her usual place of residence to another place (change in usual place of residence or UPR definition).

- The number of internal migrants in India was 450 million as per the most recent 2011 census.

- Seasonal Migrants: Economic Survey of India 2017 estimates that there are 139 million seasonal or circular migrants in the country.

- Migrant workers, who constitute about 50% of the urban population and many of whom are engaged in what are called “3D jobs” (dirty, dangerous and demeaning) are likely to face job and livelihood crisis owing to COVID-19 pandemic, according to findings of a research.

Causes of internal migration in India

- Unemployment in hinterland: An increasing number of people do not find sufficient economic opportunities in rural areas and move instead to towns and cities.

- Marriage: It is a common driver of internal migration in India, especially among women.

- Pull-factor from cities: Due to better employment opportunities, livelihood facilities etc., cities of Mumbai, Delhi, and Kolkata are the largest destinations for internal migrants in India.

About the National Migrant Policy being framed by NITI Aayog

- The draft copy of the National Migrant Policy being framed by NITI Aayog acknowledges that circular migrants are the backbone of our economy and contribute at least 10 per cent of India’s gross domestic product (GDP) and yet, tens of millions are employed in precarious jobs in the informal sector without contracts or documents to prove their identity, and claim state support in the event of a crisis.

- The draft policy is clear in highlighting the vulnerability of migrants to such crises and describes the experience of migrants during the lockdown as a “humanitarian and economic crisis”.

- It seeks to take a rights-based approach and discusses the importance of collective action and unions to help migrants bargain for better conditions and remuneration.

Involvement of line agencies

- The draft policy makes efforts to bring together different sectoral concerns related to migration, including social protection, housing, health and education. In doing so, it will lay the foundations for the ministries and line departments overseeing these sectors to work together in a more harmonious fashion, speaking the same language and operating on the same underlying assumptions.

- The draft mentions the need for convergence across different line departments and proposes the establishment of a special unit at the Ministry of Labour and Employment which will work closely with other ministries.

- All of these steps promise to create a policy environment that can better support migration and one that is based on sound data.

- The draft policy also conveys a willingness within government to recognise that the numerous laws and legislation that are in existence have not succeeded in protecting migrants as intended and recommends better implementation.

Tribal migrants sans agency?

- Tribal migration is constructed as a process whereby profiteering, “unfair” and immoral brokers or intermediaries are “luring”, or worse still, trafficking, unsuspecting tribals away from their villages.

- There is a conceptually problematic fudging of trafficking and economic migration and also a lack of clarity on how the migrants themselves perceive these processes.

- Domestic work, which is named as one of the occupations into which tribals are trafficked, has now become an important source of income for tens of thousands of women and adolescents from impoverished backgrounds in eastern Indian states working in the metropolises.

- The draft policy lists a number of government programmes and also mentions their failure in checking migration from tribal areas.

Brokers: profiteers or facilitators?

- While migrants and their families recognise that brokers exploit them and earn relatively large amounts from their migration, they also recognise that without them, they would be unable to access employment outside the village. Recruiters, whether from their own community or from outside, are key in helping migrants to negotiate the huge cultural and economic divide between their own worlds and the world of modern urban employment.

- They may do so by paying them advances which bond them to the job for several months—in the worst cases this results in perpetuating dependency and indebtedness, whereas in others it can release them from more humiliating borrowing from traditional patrons.

- The draft policy goes on to highlight other areas where migrants could be better supported including financial services, skills development, political inclusion and education, among others.

-Source: Down to Earth Magazine

EUROPEAN UNION’S CLIMATE CHANGE PLAN WORK

Context:

After the European Union became a “strategic partner” of the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc in December 2020, both blocs pledged to make climate change policy a key area of cooperation.

Relevance:

GS-III: Environment and Ecology (Climate Change, Conservation of the Environment, Pollution control and Management, Important Agreements and Treaties for Environmental Conservation)

Dimensions of the Article:

- About EUs Assistance to Southeast Asia regarding Climate Change

- Southeast Asia’s coal-powered economies

- India’s Coal Imports

- European Green Deal

- Global Climate Change Alliance Plus (GCCA+)

About EUs Assistance to Southeast Asia regarding Climate Change

- The EU has earmarked millions of euros for supporting climate friendly development in Southeast Asia but, the EU’s climate diplomacy in the region is up against economic growth fueled by dirty energy.

- After the European Union became a “strategic partner” of the Association of the Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) bloc in December 2020, both blocs pledged to make climate change policy a key area of cooperation.

- The EU, already the largest provider of development assistance to the ASEAN region, has committed millions of euros to various environmental programs.

- This includes €5 million ($5.86 million) to the ASEAN Smart Green Cities initiative and another €5 million towards a new means of preventing deforestation, called the Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade in ASEAN.

- Along with multilateral assistance, the EU also works with individual ASEAN member states on eco-friendly policies like Thailand’s Bio-Circular-Green Economic Model and Singapore’s Green Plan 2030.

- Problems Faced by the EU in Southeast Asia are that the Region’s environmental policy as Southeast Asia is going in the wrong direction in many areas on climate change. Also, 5 ASEAN states were among the fifteen countries most affected by climate change between 1999–2018, according to the Climate Risk Index 2020.

Southeast Asia’s coal-powered economies

- Southeast Asia’s energy demand is projected to grow 60% by 2040 and this will contribute to a two-thirds rise in CO2 emissions to almost 2.4 gigatons, according to the Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2019.

- Southeast Asia is one of the few areas of the world where coal usage has increased in the past decade. In 2019, the region consumed nearly double the consumption from a decade earlier, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

- Indonesia accounted for 42% and Vietnam nearly a third of the Southeast Asian coal consumption and in 2019, the region’s imports of thermal coal rose by 19% compared with the previous year, according to an IEA report.

- Energy generated from coal doubled in the Philippines between 2011 and 2018, when it accounted for 53% of energy consumption.

- Coal is expected to account for more than 50% of Vietnam’s energy supply by 2030.

- If the EU takes a strong forceful stance on coal consumption in the region, it could spark anger from the main exporters of the commodity, China, India and Australia.

Big money in dirty energy

- If the EU takes a strong forceful stance on coal consumption in the region, it could spark anger from the main exporters of the commodity, China, India and Australia.

- In 2020, Indonesia, the world’s largest palm oil producer, initiated proceedings at the World Trade Organization against the EU’s phased ban on palm-oil imports. Malaysia, the world’s second-largest palm oil producer, has vowed to stand with Indonesia in its battle against the EU.

- The EU also risks accusations of hypocrisy if it takes too forceful a stance on coal-fired energy production in Southeast Asia. Though production and consumption of coal have dropped massively in the EU in recent decades, Poland and the Czech Republic remain dependent on coal-fired energy production.

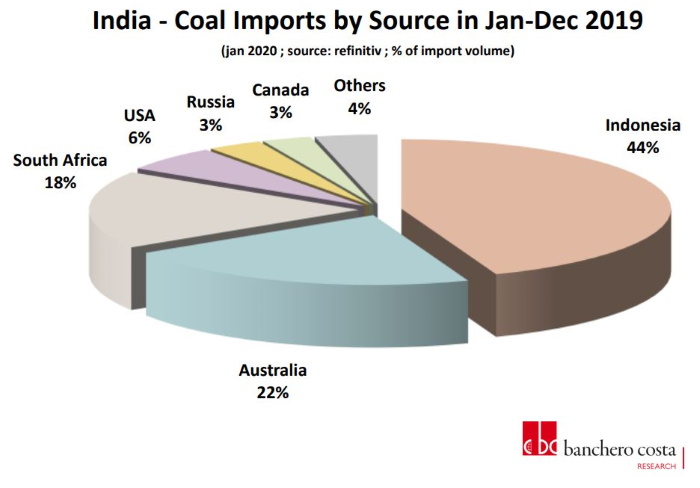

India’s Coal Imports

- Coal is among the top five commodities imported by India, the world’s largest consumer, importer and producer of the fuel.

- India imported more than 50 million tonnes of coking coal in 2019 (slightly lesser compared to 2018).

- Imports of thermal coal — mainly used for power generation — jumped more than 12 % in 2019.

- However, imports of coking coal — used mainly in the manufacturing of steel — fell marginally, following two straight years of increase, government data showed.

- While higher coal imports may be bad news for the Indian government, they benefit international miners.

European Green Deal

- The European Green Deal is a set of policy initiatives by the European Commission with the overarching aim of making Europe climate neutral in 2050.

- An impact assessed plan will also be presented to increase the EU’s greenhouse gas emission reductions target for 2030 to at least 50% and towards 55% compared with 1990 levels.

- The plan is to review each existing law on its climate merits, and also introduce new legislation on the circular economy, building renovation, biodiversity, farming and innovation.

- The EU became the first major emitter to agree to the 2050 climate neutrality target laid down in the Paris Agreement.

Global Climate Change Alliance Plus (GCCA+)

- The Global Climate Change Alliance Plus (GCCA+) is a European Union initiative designed to help the world’s most vulnerable countries address climate change.

- The GCCA/GCCA+ acts as a platform for dialogue and exchange of experience between the EU and developing countries on climate policy and on practical approaches to integrate climate change into development policies and budgets with discussions taking place at global, regional and national levels.

- The GCCA/GCCA+ also provides technical and financial support to partner countries to integrate climate change into their development policies and budgets, and to implement projects that address climate change on the ground, promoting climate-resilient, low-emission development.

- Between its founding in 2008 and 2019, it had funded over 70 projects of national, regional and worldwide scope in Africa, Asia, the Caribbean and the Pacific. The initiative helps mainly SIDS and LDCs.

- The GCCA+ also supports these group of countries in implementing their commitments resulting from the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change (COP21), in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the new European Consensus on Development.

-Source: Indian Express

SC REJECTS PLEA TO STALL DEPORTATION OF ROHINGYAS

Context:

The Supreme Court rejects a plea that had sought the release of at least 150 Rohingya refugees detained in a Jammu sub-jail and the stalling of deportation.

Relevance:

GS-II: Social Justice (Governance and Government Policies, Issues Arising Out of Design & Implementation of Policies)

Dimensions of the Article:

- About the Supreme Court judgement on the deportation of Rohingya refugees and the reactions to it

- International Laws in relation with handling Refugees

- How refugees are treated / have been treated in India?

- What is the role of Indian Judiciary in protecting refugees?

About the Supreme Court judgement on the deportation of Rohingya refugees and the reactions to it

- The SC bench added the caveat that the deportation of Rohingya refugees from Jammu must follow due procedure, which involved their proper identification and acknowledgment of their citizenship by the Myanmar government.

- The government called the Rohingya “absolutely illegal immigrants” who posed “serious threats to national security” and also contended that the right to settle in India could not be asserted by illegal immigrants under the garb of the Constitution’s Article 21, which guarantees the right to life and liberty.

- On the instructions of the Union ministry of home affairs, the Jammu & Kashmir administration started a verification drive of the Rohingya, and moved some of them to a holding centre, pending their potential deportation. India has previously deported Rohingya refugees.

- The Centre’s affidavit maintained that it has to first secure the interests of its own citizens before those of illegal immigrants who, it said, were casting a burden on the already depleting natural resources of the country in addition to posing a security threat.

- The Jammu & Kashmir administration also cautioned the bench against “starting a dangerous trend” by interfering with a subject related to illegal immigrants and diplomatic relations with another country.

International Laws in relation with handling Refugees

- Even though the refugees are foreigners in the country of asylum, by virtue of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), 1966, they could enjoy the same fundamental rights and freedoms as nationals.

- The 1951 Refugee Convention asserts that a refugee should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom, and the core principle of the convention is non-refoulement. (Refoulement means the forcible return of refugees or asylum seekers to a country where they are liable to be subjected to persecution.)

How refugees are treated / have been treated in India?

- India hosts over 2,00,000 refugees, victims of civil strife and war in Tibet, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Myanmar. Some refugees, the Tibetans who arrived between 1959 and 1962, were given adequate refuge in over 38 settlements, with all privileges provided to an Indian citizen excluding the right to vote).

- The Afghan refugees fleeing the civil war in the 1980s live in slums across Delhi with no legal status or formal documents to allow them to work or establish businesses in India.

- The Foreigners Act (1946) and the Registration of Foreigners Act (1939) currently govern the entry and exit of all refugees, treating them as foreigners without due consideration of their special circumstances.

What is the role of Indian Judiciary in protecting refugees?

- Refugees have been accorded constitutional protection by the judiciary (National Human Rights Commission vs State of Arunachal Pradesh, 1996).

- In addition, the Supreme Court has held that the right to equality (Article 14) and right to life and personal liberty (Article 21) extends to refugees.

- India remains the only significant democracy without legislation specifically for refugees. A well-defined asylum law would establish a formal refuge granting process with suitable exclusions (war criminals, serious offenders, etc.) kept.

-Source: Hindustan Times

SC ON APPOINTMENT OF AD HOC JUDGES

Context:

The Supreme Court agreed that a plan to appoint retired judges on an ad hoc basis to shear pendency in High Courts should not become an excuse to stop or further delay the appointment process of regular judges.

Relevance:

GS-II: Polity and Governance (Constitutional Provisions, Indian Judiciary)

Dimensions of the Article:

- About the Supreme Court Judgement on Ad Hoc judges

- About the pending recommendations

- Regarding appointment of Retired judges to fill the vacancies

- Ad-hoc Judges

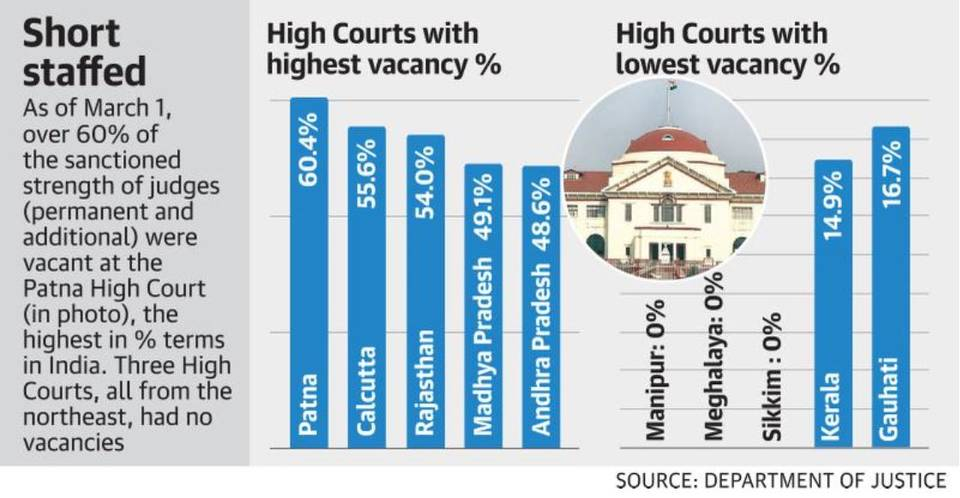

About the Supreme Court Judgement on Ad Hoc judges

- Chief Justices of State High Courts should only opt for ad hoc judges if their efforts to fill the judicial vacancies in their respective High Courts have hit a wall even as pendency has reached the red zone.

- The CJI said that the court would draw up a procedure and circumstances for appointment of ad hoc judges. The CJI said the central reason or principle for appointment of ad hoc judges in High Courts should be pendency.

Draft plan

- The remuneration of the ad hoc judges could be drawn from the Consolidated Fund of India, avoiding burden to the State exchequer.

- The Bench noted its appreciation of the government’s clearance of Collegium recommendations to the High Courts which have been pending for over six months.

About the pending recommendations

- The Supreme Court asked the Attorney General of India to enquire with the Union Ministry of Law and Justice and make a statement on the decision regarding the appointment of judges recommended by the collegium as the delay was a matter of grave concern.

- The Supreme Court Bar Association said that there was a need to institutionalise a process for considering advocates practising in the top courts to judgeships in the High Courts.

- The total sanctioned judicial strength in the 25 High Courts is 1,080. However, the present working strength is 661 with 419 vacancies as on March 1 2021.

Regarding appointment of Retired judges to fill the vacancies

- The SC bench said that retired judges could be chosen on the basis of their expertise in a particular field of dispute and allowed to retire once the pendency in that zone of law was over.

- The Bench said retired judges who had handled certain disputes and fields of law for over 15 years could deal with them faster if brought back into harness as ad-hoc judges.

- The court said the appointment of ad-hoc judges would not be a threat to the services of other judges, as Ad-hoc judges will be treated as the junior most.

Ad-hoc Judges

- The appointment of ad-hoc judges was provided for in the Constitution under Article 224A (appointment of retired judges at sittings of High Courts).

- Ad hoc judges can be appointed in the Supreme Court by “Chief Justice of India” with the prior consent of the President if there is no quorum of judges available to hold and continue the session of the court.

- Only the persons who are qualified to be appointed as Judge of the Supreme Court can be appointed as ad hoc judge of the Supreme Court (Article 127).

- Further, as per provisions of Article 128, Chief Justice of India, with the previous consent of the President, request a retired Judge of the Supreme Court High Court, who is duly qualified for appointment as a Judge of the Supreme Court, to sit and act as a Judge of the Supreme Court.

- The salary and allowances of such a judge are decided by the president.

- The retired Judge who sits in such a session of the Supreme Court has all the jurisdiction, powers and privileges of the Judges, but are NOT deemed to be a Judge.

-Source: The Hindu