Contents

- Fast-Forward: Vision 2020 for Development

- Rival territorial claims by ethnic groups can derail potential gains of Naga Accord

- Economic slowdown: Time to act fast

- Data Drive: Limping towards Sustainable Development Goals

FAST-FORWARD: VISION 2020 FOR DEVELOPMENT

Some years become landmarks in the history of countries because they are attached with important events that take place or turning points they witness.

On the other hand, some years appear more charismatic than the others because they denote certain deadlines or are easy to remember.

Some Examples

- The 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration of the World Health Organisation fixing the year 2000 for the attainment of ‘health for all’.

- Millennium Development Goals, launched in 2000, and targeted for achievement by 2015.

- Sustainable Development Goals that are to be attained by 2030, with some slated for an early deadline of 2020.

India’s Vision

Vision 2020 developed in 1998 by the government under the leadership of APJ Abdul Kalam and YS Rajan.

Technology Vision 2020:

- It was a techno-centric exercise carried out in 1996 under the aegis of the Technology Information, Information and Assessment Council (TIFAC) of the Department of Science and Technology.

- The vision exercise was driven mainly by Rajan, who was heading the technology think tank, and Kalam, who was then the scientific adviser to the Defence Minister and head of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO).

What Developed nation means?

According to the document, Developed Nation meant that “India will be one of the five biggest economic powers, having self-reliance in national security. Above all, the nation will have a standing in the world economic and political fora.”

- Imprint of technological and engineering approach to solving problems and focused a great deal on pathways to make India self-reliant in strategic sectors like materials and fine chemicals.

- For each sector, strengths were identified and a roadmap was suggested for long-term development.

- Inter-sectoral

mission-centric approach was suggested for five identified areas —

- agriculture and food processing,

- electric power,

- education and health,

- information technology

- strategic sectors.

- The Vision document did make some bold predictions and projections as well as certain prescriptions based on them, but refrained from outlining specific technology trends or futuristic technology scenarios.

- For instance, it was predicted that India will have to depend on conventional agricultural technologies while working on biotechnology-based solutions like transgenic crops for food security.

- It also talked about climate change implications for Indian agriculture even though it was early days for climate discourse. Both these predictions stand validated in 2020.

- In the same way, it was predicted that “by 2015, India will have a network which could be totally digital” and provide “full coverage within the country, provide mobile service based on the personal communication system” as well as “end-to-end high bandwidth capability at commercial centres.”

- The description has become a reality, although it was written when India barely had commercial mobile telephony and had rudimentary dial-up internet.

- One key sector where Vision 2020 remains unfulfilled is the health sector, though projections about noncommunicable diseases emerging as a major challenge in both urban and rural areas have come true.

- The document had stated that the “vision for health for all Indians is realisable well before 2020” as small solutions and change in thinking can lead to “miraculous transformation.”

- Nearly a quarter century after Technology Vision 2020, the government is repeating the same mistakes with Technology Vision 2035 which was released in 2016. Somehow, the militaristic and nationalist tilt was retained in the vision whose objective is to deploy

- “Technology in the service of India: ensuring the security, enhancing the prosperity and strengthening the identity of every Indian.”

- There was no broader engagement in the preparation of the vision document, outside the closed group of technocracy, bureaucracy and those from select IITs.

- Even after the release of the document, wider public debate and discourse has been avoided.

RIVAL TERRITORIAL CLAIMS BY ETHNIC GROUPS CAN DERAIL POTENTIAL GAINS OF NAGA ACCORD

On December 20, 2019, the Manipur Assembly passed a resolution opposing

- “Any kind of autonomy to any part of State, as a result of Framework Agreement leading to the resolution of Naga political issue”.

Reason:

- Murmurs of creation of a regional Territorial Council (TC) for the Nagas of Manipur as part of the Indo-Naga accord.

- Territorial Council is a term used when the territorial limits of councils under Sixth Schedule extend beyond one district.

- Manipur’s integrity has dominated politics in the Meitei-dominated plain areas for the last 20 years.

- As it becomes clear that the government is considering granting local autonomy in the form of the TC to the Nagas of Manipur in lieu of integration, the cry for protecting Manipur’s “territorial integrity” subtly transforms into preserving “the present administrative set up” of the state.

- Manipur has been largely inhabited by three broad ethnic groups.

- The Naga and Zomi-Kuki tribes in the north and south have long claimed that they have never been part of Manipur historically and have demanded separation from it.

- The task of defending Manipur’s territorial integrity, therefore, falls on the majority Meitei community who occupy the middle plains. They have so far succeeded in preserving the status quo.

- The Naga and Zomi-Kuki tribes’ demand for separation from Manipur is aligned with their aspiration for political integration with their cognate tribe-groups in the surrounding states and countries. The Nagas’ struggle for territorial integration is well known.

- Zo tribes also want to politically re-unite their lands in present day Mizoram, the south districts of Manipur, and the Chin Hills of Burma.

- Administratively, the major divide in Manipur is between the plain areas and the hill areas.

- The entire “Hill Areas”, covering both Naga and Zomi-Kuki tribes, always had a uniform structure of administration.

- In terms of local autonomy, there are the Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) set up by an Act of Parliament in 1971.

- There are six ADCs covering the hill areas of Manipur.Unlike the ADCs elsewhere, the ADCs in Manipur are not under the Sixth Schedule.

- According to reports, the proposed Manipur Naga TC will be bolstered with provisions akin to Article 371A of the Constitution.

- Article 371A gives the Nagaland Assembly overriding powers over the Indian Parliament in respect of the Nagas’ customary laws, religious and social practices, and land and its resources.

- If the Naga TC is created, it will be the first time in Manipur’s history that the state’s administrative structure is rearranged on ethnic lines.

- Demarcating “Naga areas” from the rest will itself be a challenge because there are overlapping claims on territories. Manipur will take the form of three ethnic conclaves cohabiting out of necessity.

- One option is for the parties to agree to demarcating the boundary by a neutral body. Else, it may come down to upgrading the existing ADCs together and simultaneously to a higher status under the Sixth Schedule. Or, converting existing ADCs into a single TC covering the entire hill area.

- This will keep the boundaries ethnic-neutral and preclude fights over claimed ancestral homelands.

- It will assuage the Meitei’s fears on this score. Manipur will remain intact. This will, of course, be too little for some and too much for others. But under the circumstances, it may be the safest way forward.

ECONOMIC SLOWDOWN: TIME TO ACT FAST

Perception problem

- Today, the perception in India Inc, and outside of it, is that the current establishment ‘favors’ a few business houses that have its ear, and is willing to help them even if it is at a huge cost to others

- The other perception is that the government is fearful of being labelled a suit-boot-Ki-Sarkar and, therefore, refrains from showing open support for industry.

Measures so far:

Corporate Tax cuts:

- The objective of the cut was to attract foreign players to invest in India

- However after the Vodafone episode—with Kumar mangalam Birla saying it would need to shut shop unless there was some relief on the AGR payments—global corporations cannot be blamed for being wary of investing large sums in India.

- At some point, this could tell on FDI inflows; between April and October, 2019, the flows of $40 billion were up only about 8% over the corresponding period of FY19.

- To be sure, there will be investors—Lakshmi Mittal’s Arcelor Steel has brought in some $7 billion to buy EssarSteel. But, by and large, it is the services sector—e-commerce, banking, insurance—that have attracted FDI flows rather than defense or manufacturing.

Merely cutting the corporation tax rate isn’t enough though.

- The reality on the ground is that it is very difficult to do business in India given the red tape, and corruption

- In fact, after promising reform in labour laws, all that the government has done is to say it would support state governments in their efforts to ease the rules

Some Steps to encourage Foreign capital

- The government should desist from favouring local players who believe they have the right to control the business even if they are not the majority shareholders

- Rules, once framed, should not be changed later, after investments have been made

- Government needs to demonstrate—with policy action—that it is unbiased, and willing to reform

DATA DRIVE: LIMPING TOWARDS SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

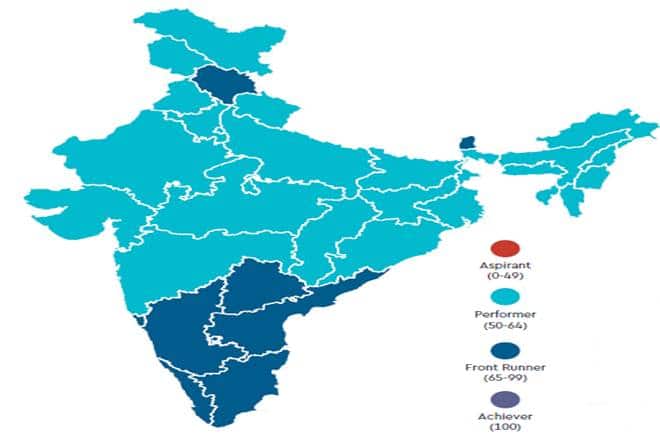

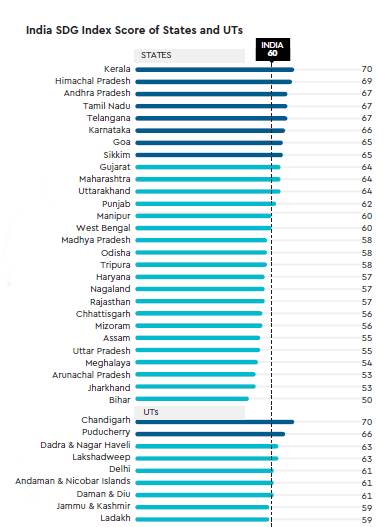

- The recently published Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Index 2019-20 by the NITI Aayog gives India an overall score of 60

- Kerala (70) topped the list, while Bihar (50) was at the bottom

- The marginal improvement in the overall score for India has been due to its improvement in the areas of clean water and sanitation, affordable and clean energy, and innovation

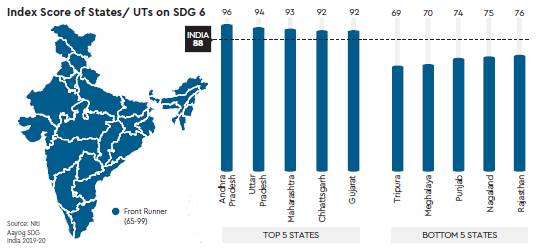

- With regards to SDG 6—clean water and sanitation—India’s overall score is 88. Andhra Pradesh (96) was the best performing state and Tripura (69) the worst.

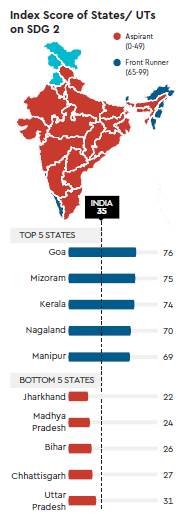

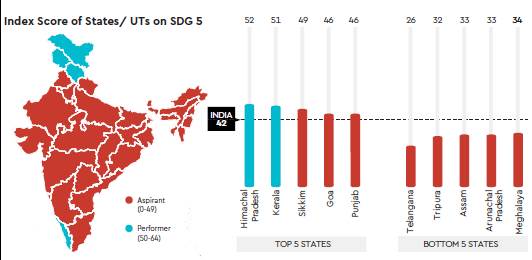

- The fact that there has only been marginal improvement is because India is limping with the other SDGs—mainly zero hunger (SDG 2) and gender equality (SDG 5).

- India’s overall score in SDG 2 is 35, with states’ scores ranging from 22 to 76—Goa has the highest score and Jharkhand the lowest

- India is facing high levels of malnutrition and hunger—it is ranked 102 on the Global Hunger Index—we should tackle this at the earliest.

- Indicators such as low sex ratio (896 per 1,000 males), low political representation, gender wage gap and informality of labour have contributed to India’s overall score of SDG 5 which is 42