Contents

- National Policy for Rare Diseases, 2021

- COVID: Increase in maternal deaths and stillbirths

- NGT: Strengthen HSPCB and other direction to CPCB

- Article 244 (A): Its relevance for Assam hill tribes

NATIONAL POLICY FOR RARE DISEASES, 2021

Context:

Caregivers to patients with ‘rare diseases and affiliated organisations are dissatisfied with the National Policy for Rare Diseases, 2021 announced recently.

Relevance:

GS-II: Social Justice (Health related issues, Governance and Government Policies, Issues Arising Out of Design & Implementation of Policies)

Dimensions of the Article:

- What are ‘Rare diseases’?

- Pressing Issues regarding ‘Rare diseases’

- Provisions of the National Rare Disease Policy 2021

- Criticisms of the National Rare Disease Policy 2021

- Constitutional Provisions in the context of the new policy for rare diseases

What are ‘Rare diseases’?

A rare disease, also referred to as an orphan disease, is any disease that affects a small percentage of the population.

Most rare diseases are genetic, and are present throughout a person’s entire life, even if symptoms do not immediately appear.

- Haemophilia,

- Thalassemia,

- Sickle-cell anaemia,

- Auto-immune diseases,

- Pompe disease,

- Hirschsprung disease,

- Gaucher’s disease,

- Cystic Fibrosis,

- Hemangiomas and

- Certain forms of muscular dystrophies

Are some of the most common rare diseases recorded in India.

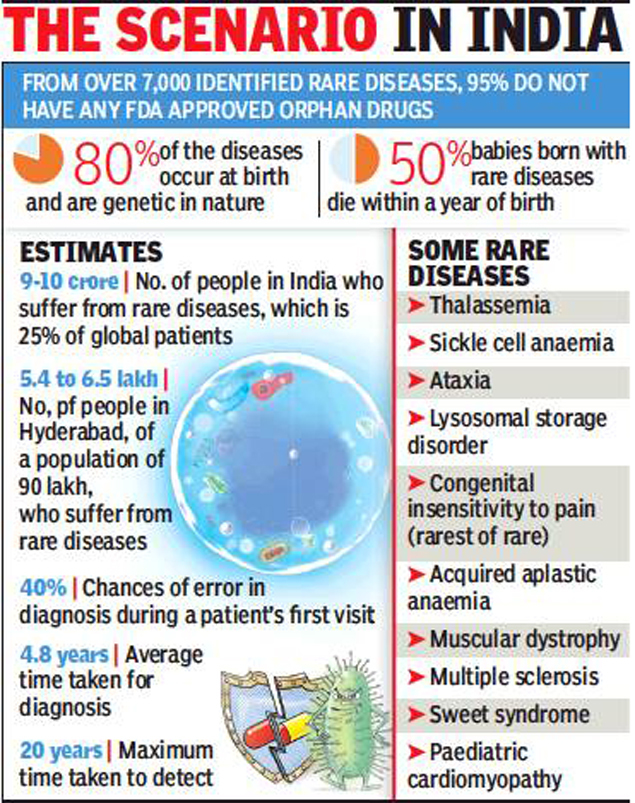

Pressing Issues regarding ‘Rare diseases’

- Rare diseases pose a significant challenge to health care systems because of the difficulty in collecting epidemiological data, which in turn impedes the process of arriving at a disease burden, calculating cost estimations and making correct and timely diagnoses, among other problems.

- There are 7,000-8,000 classified rare diseases, but less than 5% have therapies available to treat them.

- About 95% rare diseases have no approved treatment and less than 1 in 10 patients receive disease-specific treatment. Where drugs are available, they are prohibitively expensive, placing immense strain on resources.

- These diseases have differing definitions in various countries and range from those that are prevalent in 1 in 10,000 of the population to 6 per 10,000.

- India has said it lacks epidemiological data on the prevalence here and hence has only classified certain diseases as ‘rare.’

- Currently, only a few pharmaceutical companies are manufacturing drugs for rare diseases globally and there are no domestic manufacturers in India except for those who make medical-grade food for those with metabolic disorders.

- Due to the high cost of most therapies, the government has not been able to provide these for free.

Provisions of the National Rare Disease Policy 2021

- Patients of rare diseases will be eligible for a one-tome treatment under the Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY).

- Financial support up to Rs20 lakh under the Umbrella Scheme of Rashtriya Arogaya Nidhi shall be provided by the central government for treatment of those rare diseases that require a one-time treatment (diseases listed under Group 1) for their treatment in Government tertiary hospitals only. – (NOT be limited to below poverty line (BPL) families, but extended to about 40% of the population as eligible under the norms of Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY))

The policy has categorised rare diseases in three groups:

- Disorders amenable to one-time curative treatment;

- Those requiring long term or lifelong treatment; and

- Diseases for which definitive treatment is available but challenges are to make optimal patient selection for benefit.

The government has said that it will also assist in voluntary crowd-funding for treatment as it will be difficult to fully finance treatment of high-cost rare diseases.

Criticisms of the National Rare Disease Policy 2021

- Though the document specifies increasing the government support for treating patients with a ‘rare disease’— from Rs 15 lakh to Rs 20 lakh — caregivers say this doesn’t reflect actual costs of treatment.

- The Policy leaves patients with Group 3 rare diseases to fend for themselves due to the absence of a sustainable funding support.

- What the policy doesn’t capture is that these are diseases that last a lifetime adding up to a huge amount of expenditure and many of the patients who can’t afford such treatment will be unable to even make it to the prescribed tertiary hospitals for treatment.

Constitutional Provisions in the context of the new policy for rare diseases

- Article 38 says that the state will secure a social order for the promotion of welfare of the people. Providing affordable healthcare is one of the ways to promote welfare.

- Article 41 imposes duty on state to provide public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness and disablement etc.

- Article 47 makes it the duty of the State to improve public health, securing of justice, human condition of works, extension of sickness, old age, disablement and maternity benefits and also contemplated.

-Source: The Hindu

COVID: INCREASE IN MATERNAL DEATHS AND STILLBIRTHS

Context:

The failure of the health system to cope with COVID-19 pandemic resulted in an increase in maternal deaths and stillbirths, according to a study published in The Lancet Global Health Journal.

Relevance:

GS-II: Social Justice (Issues Related to Women and Children, Health related issues)

Dimensions of the Article:

- What is Maternal Mortality Ratio?

- Recent decrease in MMR and its reasons

- Highlights of the Lancet report

- Way Forwards suggested

What is Maternal Mortality Ratio?

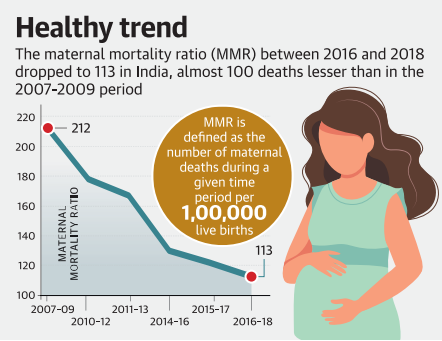

- Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is the annual number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births.

- Maternal death is the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy.

- It is a key performance indicator for efforts to improve the health and safety of mothers before, during, and after childbirth.

Recent decrease in MMR and its reasons

- The Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in India has declined to 113 in 2016 – 18 from 122 in 2015 – 17 and 130 in 2014-2016, according to the special bulletin on Maternal Mortality in India 2016 – 18, released by the Office of the Registrar General’s Sample Registration System (SRS).

- The MMR of various States according to the bulletin includes Assam (215), Bihar (149), Madhya Pradesh (173), Chhattisgarh (159), Odisha (150), Rajasthan (164), Uttar Pradesh (197) and Uttarakhand (99).

- The southern States registered a lower MMR Andhra Pradesh (65), Telangana (63), Karnataka (92), Kerala (43) and Tamil Nadu (60).

Reasons for Declining MMR:

- Focus on quality and coverage of health services through public health initiatives have contributed majorly to the decline. Some of these initiatives are:

- LaQshya,

- Poshan Abhiyan,

- Janani Suraksha Yojana,

- Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan

- Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana,

- The implementation of the Aspirational District Programme and inter-sectoral action has helped to reach the most marginalized and vulnerable population.

- Recently launched Surakshit Matritva Aashwasan Initiative (SUMAN) especially focuses on zero preventable maternal and newborn deaths.

- The continuous progress in reducing the MMR will help the country to achieve the SDG 3 target of MMR below 70 by 2030.

Highlights of the Lancet report

- Overall, there was a 28% increase in the odds of stillbirth, and the risk of mothers dying during pregnancy or childbirth increased by about one-third.

- There was also a rise in maternal depression.

- COVID-19 impact on pregnancy outcomes was disproportionately high on poorer countries.

Way Forwards suggested

- Policy makers and healthcare leaders must urgently investigate robust strategies for preserving safe and respectful maternity care, even during the ongoing global emergency.

- Immediate action is required to avoid rolling back decades of investment in reducing mother and infant mortality in low-resource settings.

- The authors recommend that personnel for maternity services not be redeployed for other critical and medical care during the pandemic and in response to future health system shocks.

- Further, wider societal changes could have also led to deterioration in maternal health including intimate-partner violence, loss of employment and additional care-responsibilities because of closure of schools.

-Source: The Hindu

NGT: STRENGTHEN HSPCB AND OTHER DIRECTION TO CPCB

Context:

- The National Green Tribunal (NGT), in a landmark judgement, directed Haryana State Pollution Control Board (HSPCB) to strengthen its capacity, both in terms of human resource and setting up of modern laboratories.

- NGT also directed the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) to prepare recruitment rules to be followed by all states, mechanism for annual performance audit of SPCBs or pollution control committees (PCC), among other things.

Relevance:

GS-III: Environment and Ecology (Conservation of Environment and Ecology, Government Policies and Interventions, Important Organizations)

Dimensions of the Article:

- National Green Tribunal (NGT)

- Structure of National Green Tribunal

- Powers of NGT

- Challenges related NGT:

- Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB)

- Recent orders of the NGT:

- Impact of these orders

National Green Tribunal (NGT)

- The NGT was established on October 18, 2010 under the National Green Tribunal Act 2010, passed by the Central Government.

- National Green Tribunal Act, 2010 is an Act of the Parliament of India which enables creation of a special tribunal to handle the expeditious disposal of the cases pertaining to environmental issues.

- NGT Act draws inspiration from the India’s constitutional provision of (Constitution of India/Part III) Article 21 Protection of life and personal liberty, which assures the citizens of India the right to a healthy environment.

- The stated objective of the Central Government was to provide a specialized forum for effective and speedy disposal of cases pertaining to environment protection, conservation of forests and for seeking compensation for damages caused to people or property due to violation of environmental laws or conditions specified while granting permissions.

Structure of National Green Tribunal

- Following the enactment of the said law, the Principal Bench of the NGT has been established in the National Capital – New Delhi, with regional benches in Pune (Western Zone Bench), Bhopal (Central Zone Bench), Chennai (Southern Bench) and Kolkata (Eastern Bench). Each Bench has a specified geographical jurisdiction covering several States in a region.

- The Chairperson of the NGT is a retired Judge of the Supreme Court, Head Quartered in Delhi.

- Other Judicial members are retired Judges of High Courts. Each bench of the NGT will comprise of at least one Judicial Member and one Expert Member.

- Expert members should have a professional qualification and a minimum of 15 years’ experience in the field of environment/forest conservation and related subjects.

Powers of NGT

The NGT has the power to hear all civil cases relating to environmental issues and questions that are linked to the implementation of laws listed in Schedule I of the NGT Act. These include the following:

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974;

- The Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Cess Act, 1977;

- The Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980;

- The Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981;

- The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986;

- The Public Liability Insurance Act, 1991;

- The Biological Diversity Act, 2002.

This means that any violations pertaining ONLY to these laws, or any order / decision taken by the Government under these laws can be challenged before the NGT.

Importantly, the NGT has NOT been vested with powers to hear any matter relating to the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, the Indian Forest Act, 1927 and various laws enacted by States relating to forests, tree preservation etc.

Challenges related NGT:

- Two important acts – Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 and Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006 have been kept out of NGT’s jurisdiction. This restricts the jurisdiction area of NGT and at times hampers its functioning as crucial forest rights issue is linked directly to environment.

- Decisions of NGT have also been criticised and challenged due to their repercussions on economic growth and development.

- The absence of a formula based mechanism in determining the compensation has also brought criticism to the tribunal.

- The lack of human and financial resources has led to high pendency of cases – which undermines NGT’s very objective of disposal of appeals within 6 months.

Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB)

- The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) of India is a Statutory Organisation under the Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF).

- It was established in 1970s under the Water (Prevention and Control of pollution) Act.

- CPCB is the apex organisation in country in the field of pollution control.

- It is also entrusted with the powers and functions under the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981.

- It serves as a field formation and also provides technical services to the Ministry of Environment and Forests under the provisions of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

- It Co-ordinates the activities of the State Pollution Control Boards by providing technical assistance and guidance and also resolves disputes among them.

Recent orders of the NGT:

The NGT passed an order for the Haryana government to revisit its inspection policy and make it adequate to ensure effective enforcement of law.

Orders to CPCB:

- Conduct Inspection at higher frequencies.

- Enhance capacity of SPCBs/Pollution Control Committees (PCCs) with consent funds.

- Enhance capacity of CPCB utilising environment compensation funds.

- Audit the Annual performance of state PCBs/PCCs.

- Prepare a format containing qualifications, minimum eligibility criteria and required experience for key positions.

Impact of these orders

- In the name of ‘ease of doing business’, powers and authorities of SPCB have been compromised. The latest judgement of NGT is a fresh start to the long-delayed initiative of strengthening CPCB/SPCBs/PCCs.

- The judgment of NGT could be termed as landmark. The NGT has tried to erase the bottlenecks, which were being used to halt the strengthening of environmental regulation.

- The important part of the judgement is asking CPCB to come out with standard recruitment rules which can be followed by all states. The existing SPCBs recruitment rules have not been updated for decades.

-Source: Down to Earth

ARTICLE 244 (A): ITS RELEVANCE FOR ASSAM HILL TRIBES

Context:

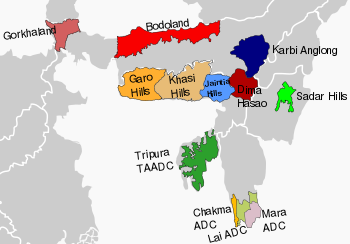

As the hill districts of Dima Hasao, Karbi Anglong and West Karbi Anglong go to polls, the demand for an autonomous state within Assam has been raised by some of the sections of the society under the provisions of Article 244A of the Constitution.

Relevance:

GS-II: Polity and Governance (Constitutional Provisions), GS-I: Issues related to SCs and STs)

Dimensions of the Article:

- What is Article 244(A) of the Constitution?

- Special Status of Sixth Schedule Areas

- About Autonomous District Councils (ADCs)

- How is 244A different from the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution?

- Background to the current demand for autonomous state:

What is Article 244(A) of the Constitution?

- The 22nd Amendment of the Constitution of India, 1969, inserted new article 244A in the Constitution to empower Parliament to enact a law for constituting an autonomous State within the State of Assam.

- The parliament can also provide the autonomous State with Legislature or a Council of Ministers or both with such powers and functions as may be defined by that law, under Article 244A.

Other provisions of the 22nd Amendment

- The 22nd Amendment amended article 275 in regard to sums and grants payable to the autonomous State on and from its formation under article 244A.

- It also inserted new article 371B which provided for constitution and functions of a committee of the Legislative Assembly of the State of Assam consisting of members of that Assembly elected from the tribal areas specified in the Sixth Schedule.

Special Status of Sixth Schedule Areas

- The Sixth Schedule was originally intended for the predominantly tribal areas (tribal population over 90%) of undivided Assam, which was categorised as “excluded areas” under the Government of India Act, 1935 and was under the direct control of the Governor.

- The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution provides for the administration of tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram to safeguard the rights of the tribal population in these states.

- In Assam, the hill districts of Dima Hasao, Karbi Anglong and West Karbi and the Bodo Territorial Region are under this provision.

- The Sixth Schedule provides for autonomy in the administration of these areas through Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) and the special provision is provided under Article 244(2) and Article 275(1) of the Constitution.

- The Governor is empowered to increase or decrease the areas or change the names of the autonomous districts. While executive powers of the Union extend in Scheduled areas with respect to their administration in fifth schedule, the sixth schedule areas remain within executive authority of the state.

About Autonomous District Councils (ADCs)

- The Autonomous districts and regional councils (ADCs) are empowered with civil and judicial powers can constitute village courts within their jurisdiction to hear the trial of cases involving the tribes.

- Governors of states that fall under the Sixth Schedule specify the jurisdiction of high courts for each of these cases.

- Along with ADCs, the Sixth Schedule also provides for separate Regional Councils for each area constituted as an autonomous region.

- In all, there are 10 areas in the Northeast that are registered as autonomous districts – three in Assam, Meghalaya and Mizoram and one in Tripura.

- These regions are named as district council of (name of district) and regional council of (name of region).

- Each autonomous district and regional council consist of not more than 30 members, of which four are nominated by the governor and the rest via elections, all of whom remain in power for a term of five years.

How is 244A different from the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution?

- The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution — Articles 244(2) and 275(1) — is a special provision that allows for greater political autonomy and decentralized governance in certain tribal areas of the Northeast through autonomous councils that are administered by elected representatives. In Assam, the hill districts of Dima Hasao, Karbi Anglong and West Karbi and the Bodo Territorial Region are under this provision.

- Article 244(A) accounts for more autonomous powers to tribal areas. According to Uttam Bathari, who teaches history at Gauhati University, among these the most important power is the control over law and order.

Background to the current demand for autonomous state:

- In the 1950s, a demand for a separate hill state arose around certain sections of the tribal population of undivided Assam. In 1960, various political parties of the hill areas merged to form the All Party Hill Leaders Conference, demanding a separate state. After prolonged agitations, Meghalaya gained statehood in 1972.

- The leaders of the Karbi Anglong and North Cachar Hills were also part of this movement and they were given the option to stay in Assam or join Meghalaya. The chose to stay in Assam as the then government promised more powers, including Article 244 (A) and since then, there has been a demand for Autonomous state.

- 2021, 1,040 militants of five militant groups of Karbi Anglong district ceremonially laid down arms at an event in Guwahati in the presence of Chief Minister Sarbananda Sonowal, the entire political discourse here still revolves around the demand for grant of ‘autonomous state’ status to the region.

-Source: Indian Express