Contents

- The marginalisation of justice in public discourse

- It takes two: Urban and Rural Economic Recovery

- The jump in forex reserves may not be a positive sign

THE MARGINALISATION OF JUSTICE IN PUBLIC DISCOURSE

Focus: GS-II Social Justice

Introduction

- The pursuit of greed and narrow self-interest leads to severe inequalities, to an unequal division of social benefits.

- Given the compulsion to advance our self-interest, the burden is easily passed on to those among us who are powerless to desist it.

- In simple words: The poor cannot afford to reject the excess work burden placed upon them due to their dire necessity to work and escape poverty.

Sharing benefits and burdens

- The idea of distributive justice presupposes not only a social condition marked by an absence of love or familiarity, but also others which the Scottish philosopher, David Hume, termed ‘the circumstances of justice’.

- For instance, a society where everything is abundantly available would not need justice. Each of us will have as much of everything we want. Without the necessity of sharing, justice becomes redundant.

- Equally, in a society with massive scarcity, justice is impossible. In order to survive, each person is compelled to grab whatever happens to be available. Justice, therefore, is possible and necessary in societies with moderate scarcity.

Giving persons their due

- The basic idea of justice is that ‘each person gets what is properly due to him or her’, that the benefits and burdens of society be distributed in a manner that gives each person his or her due.

Hierarchical and Egalitarian notions

- In hierarchical notions, what is due to a person is established by her or his place within a hierarchical system. For instance, by rank determined at birth. Certain groups are born privileged. Therefore, their members are entitled to a disproportionately large share of benefits, and a disproportionately small share of burdens. On this conception, justice requires that the benefits and burdens be unequally shared or distributed. Conversely, those born in ‘low castes’ get whatever is their proper due — very little, sometimes nothing.

- Innumerable examples can be cited in Indian history, where aspects of this hierarchical notion had been opposed: in the early teachings of the Buddha, passages in Indian epics, Bhakti poetry, and protest movements such as Veerashaivism.

- All have an equal, originary capacity of endowing the world with meaning and value because of which they possess moral worth or dignity.

- People must first struggle for recognition as equals, for what might be called basic social justice, then they must decide how to share all social benefits and burdens among equal persons — the essence of egalitarian distributive justice.

Needs and Desert

- Two main contenders exist for interpreting what is due to persons of equal moral worth.

- For the first need-based principle,what is due to a person is what she really needs, i.e., whatever is necessary for general human well-being.

- Second, the principle of desert for which what is due to a person is what he or she deserves, determined not by birth or tradition but by a person’s own qualities, for instance ‘natural’ talent or productive effort.

- In short, though we start as equals, those who are talented or work hard should be rewarded with more benefits and be less burdened.

Break the deafening silence

- Most reasonable egalitarian conceptions of justice try to find a balance between need and desert.

- They try to ensure a distribution of goods and abilities (benefits) that satisfies everyone’s needs, and a fair distribution of social burdens or sacrifices required for fulfilling them.

- After this, rewards are permissible to those who by virtue of natural gift, social learning and personal effort, deserve more.

-Source: The Hindu

IT TAKES TWO: URBAN AND RURAL ECONOMIC RECOVERY

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Introduction

- Over the past month or so, leading economic indicators have pointed towards a two-paced recovery.

- Sales of tractors and two-wheelers, proxies of rural demand, appear to have rebounded strongly, indicating that the pickup in rural areas has been swifter than in the urban centres which have borne the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- In large part, this optimism over the relatively stronger rural recovery stems from the healthy performance of the agricultural sector which was excluded from the lockdown restrictions.

Details

- As per CARE Ratings, the agriculture, forestry and fishing sector is likely to grow by 3.5 per cent in the first quarter of the current financial year.

- This implies that for the first time since quarterly estimates of growth have been published, the farm sector is likely to register positive growth even as the rest of the economy contracts (barring the government sector).

Reasons

- The strong performance of the farm sector has been on the back of a good rabi harvest — the Agriculture Ministry has pegged the output of wheat, chana and other rabi crops.

- Total area under kharif coverage was up 9 per cent as compared to the previous year. Higher food inflation in some commodities may also lead to greater realisations for farmers.

- This rise in agricultural activity, coupled with higher allocations to the MGNREGA (total outlay under the scheme has risen to a record high of Rs 1 lakh crore this year) also appears to have led to a sharp drop in rural unemployment during this period, as observed in the CMIE data.

The Other side of the story

- However, healthy growth of the farm sector, even if it continues, is unlikely to offset the economic losses suffered by other parts of the economy.

- The declining share of agriculture in rural household incomes — sectors like construction now account for a sizeable portion — implies that prospects of a broad-based rural recovery remain uncertain.

- As the Reserve Bank of India noted in its annual report, fuller recovery in rural areas is being “held back by muted wage growth which is still hostage to migrant crisis and associated employment losses.”

Conclusion

- As rural households depend on sectors like construction, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade to a greater extent than before, how these activities shape up will determine the pace of revival of the broader rural economy.

- This in turn depends on the trajectory of the pandemic and is a consequence of how economic activities shape up in urban areas.

-Source: Indian Express

THE JUMP IN FOREX RESERVES MAY NOT BE A POSITIVE SIGN

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Why in news?

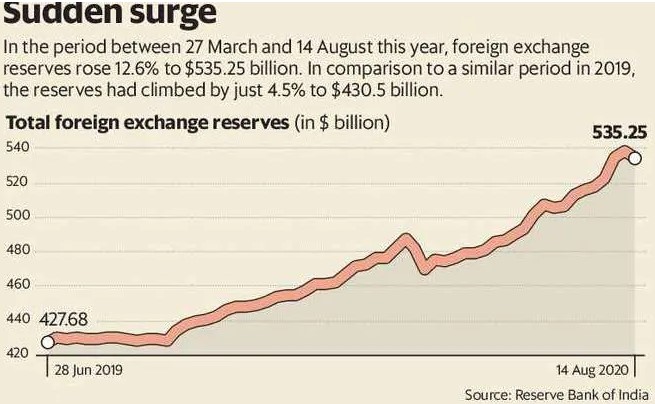

Amid the covid-19 pandemic, India’s foreign exchange (forex) reserves have been going up at a very fast pace and have touched a new high, in absolute terms, almost every week.

- Clearly, there has been a very rapid increase in the country’s foreign exchange reserves since March-end, after the negative economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic was first felt.

- Some economic and political commentators have tried to pass this increase as evidence of improvement in the overall state of the economy.

What does this jump in forex reserves signify?

- A large part of the foreign exchange reserves is used to pay for imports.

- Since imports of goods fell, consequently lesser reserves have been used to pay for imports.

- This essentially shows a slump in economic activity since the onset of lockdown.

- India imports a large part of the crude oil that it consumes, and the total oil and petroleum products imports have fallen by 55.9% to $19.6 billion, a clear impact of the lockdown.

- While imports fell by 46.7% in the first four months, goods exports fell by 30.3%, hence, trade deficit, the difference between imports and exports, fell by 76.5%.

- The difference in trade was more than made up for through other sources, pushing up the reserves.

What other sources have aided reserves?

- Besides reduced imports, there are other factors that have pushed forex reserves up.

- As the price of gold has increased, the value of gold held by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has jumped by 21.7%.

- Over and above this, with people not leaving India for holidays, business trips or education, the demand for foreign exchange while travelling abroad, has taken a beating.

Do foreign investors have any role to play?

- Foreign institutional investors (FIIs) bring money primarily in dollars. These dollars need to be exchanged for rupees before they can be invested.

- FIIs have brought in more than $10 billion this year into India and this money has ended up with RBI as foreign exchange reserves.

-Source: Livemint