Contents

- Pressure and punishment

- No Minister, the trade agreement pitch is flawed

PRESSURE AND PUNISHMENT

Context:

The conviction of Hafiz Saeed, a UN-designated terrorist whom India and the U.S. blame for the 2008 Mumbai terror attacks that killed 166, by a Lahore anti-terrorism court on terror finance charges shows that Pakistan can be forced to act against terror networks under international pressure.

Relevance:

GS Paper 3: Linkages of Organized crime and Terrorism

Mains Questions

- The scourge of terrorism is a grave challenge to national security. What solutions do you suggest to curb this growing menace? What are the major sources of terrorist funding? 15 marks

- “Terrorism is emerging as a competitive industry over the last few decades.” Analyse the above statement. 15 marks

Dimensions of the Article

- What is Terror Funding?

- Sources of terror financing

- Challenges of fighting against terror financing

- Steps taken to combat terror financing

- Way forward

What is Terror Financing?

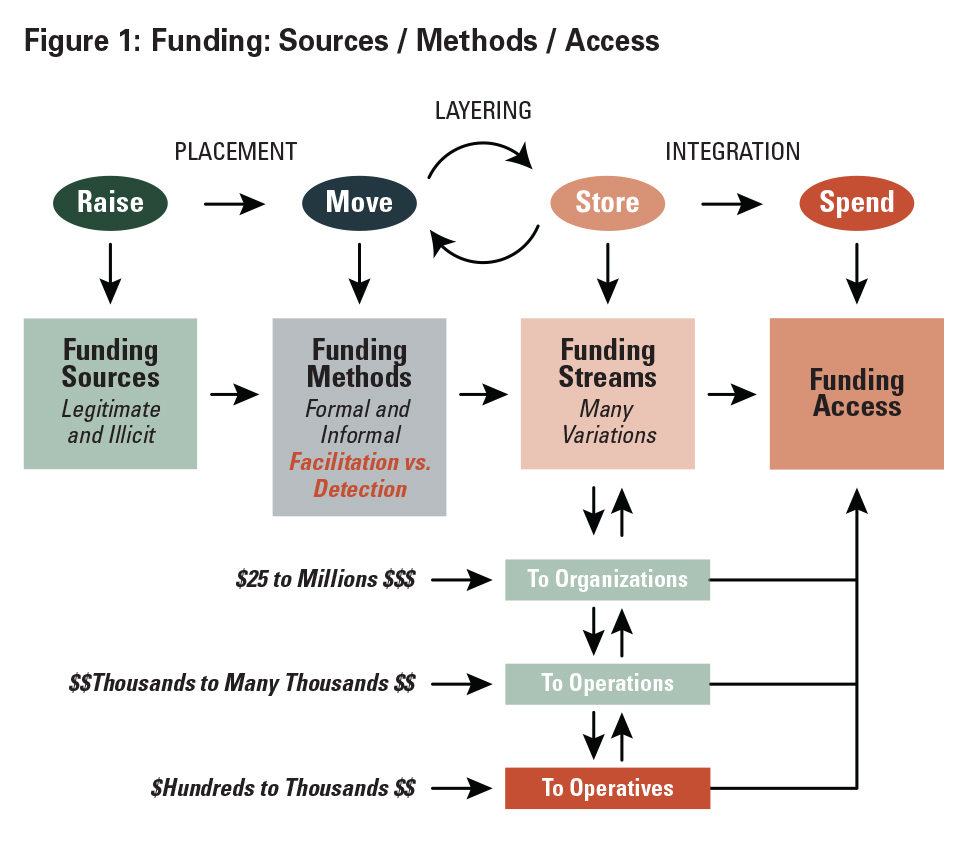

Terrorist financing involves the solicitation, collection or provision of funds with the intention that they may be used to support terrorist acts or organizations.

- Terror organizations through a wide range of de-centralized and self-directed network mobilize funds for meeting their organizational expenses.

- Funds may stem from both legal and illicit sources.

- In 2015, the Islamic State (IS) emerged as the world’s richest terrorist organisation with a budget of nearly $1.7 billion.

Sources of terror financing

- Financial support from state entities- that can generate the funds and ensures its long term availability

- Self-funding- through their local contributions, donations, Zaquat, overseas collections among others.

- Diversion of funds– by non-governmental and charitable organizations

- Revenue generating activities: Criminal activities from low level fraud to well-planned crimes, extortion, protection money, drug trafficking, gun running, counterfeiting etc. e.g. the Al-Shabab (Somalia) profit from wildlife poaching and the ivory-trade.

- Legitimate businesses such as investments in local businesses, commercial enterprises acting as front companies, real estate dealings etc.

- De-Centralisation of Terror E.g. The Al Qaida convinced its followers to build bombs at home.

Indian Scenario

- A distinct linkage between crime and money laundering in terror financing characterizes Indian scenario.

- It is also evident that three stage progression of terror financing – state sponsored, privatized and globalized finance of terrorism, has been in operation in promoting and sustaining terrorism in India.

- Naga Insurgency– was supported by China in the form of training, weapons and finances in the sixties and mid-seventies.

- Indian Mujahedeen- have been supported by Pakistan which used the ‘trinity’ network of globalization, privatization and criminal activities in tandem.

- Thus, due to its intricate nature, terror financing has turned into a complex challenge for the policy makers and law enforcing agencies of India.

Challenges of fighting against terror financing

- Difficult to prove illegality of financing– terrorism is inherently illegal, while terrorism finance, unless proved and linked with terrorism, could continue to remain a completely legal process.

- Involves multiple complex processes- from generation of funds for terror and its movement from varied sources to the final destination.

- Involves multiple players– including internal as well as external state and non-state actors.

- Seamless integration– terrorism finance rides over a financial network, which is seamless and transcends geographical boundaries. This implies application of multiple laws in different countries, which often makes prosecution complicated, and creates lacunae in their interpretation.

- Sensitivity of some collections– collection of funds for charitable purposes is often a sensitive issue and can have religious overtones. e.g. Zakat, as a means of collecting charity in countries like Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, has been misused in the past and funnelled for terrorism finance.

- Faster evolution of ways of terror financing– than most monetary systems and regulatory mechanisms. Majorly, the authorities focus on old systems like hawala for transferring value, to e-commerce in the cyber world etc. However, there are reports of new ways of terror financing, such as “digital laundering”.

- Terrorism finance continues to change its sourcing and means of transit of funding, thereby making it more difficult to detect.

- Difficult to catch small financing– most acts of terrorism require very little funding to execute. Therefore, the pursuit of large and abnormal fund transfers with the aim of stalling such attacks is likely to result in failure.

Steps taken to combat terror financing in the country

- Strengthening the provisions in the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 to combat terror financing by criminalizing the production or smuggling or circulation of high quality counterfeit Indian currency as a terrorist act and enlarge the scope of proceeds of terrorism to include any property intended to be used for terrorism.

- A Terror Funding and Fake Currency (TFFC) Cell has been constituted in National Investigation Agency (NIA) to conduct focused investigation of terror funding and fake currency cases.

- A Financial Intelligence Unit has been constituted to combat trans-national movement of illicit funds

- An advisory on terror financing has been issued in April 2018 to States/ Union Territories. Guidelines have also been issued in March, 2019 to States/ Union Territories for investigation of cases of high quality counterfeit Indian currency notes.

- Training programmes are regularly conducted for the State Police personnel on issues relating to combating terrorist financing.

- FICN Coordination Group (FCORD) has been formed by the Ministry of Home Affairs to share intelligence/information among the security agencies of the states/centre to counter the problem of circulation of fake currency notes.

Global and Regional Efforts

- India-U.S. Economic and Financial Partnership Dialogue provides for information sharing between the two countries’ regulatory agencies.

- India is also consistently urging the UN member states to adopt a global terrorism treaty – the Comprehensive Convention on International terrorism.

- SAARC countries have accepted the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism of 1999 and UNSCR 1267.

- Financial Action Task Force (FATF)- is an intergovernmental body established in 1989 & is mandated to set global protocols and standards to combat money laundering and other financial crimes with direct ramifications to terrorist acts across the globe.

- Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering- is an intergovernmental organisation, consisting of 41 member jurisdictions, focused on ensuring that its members effectively implement the international standards against money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing related to weapons of mass destruction.

Way Forward

- A comprehensive and effective legal framework to deal with all aspects of terrorism needs to be enacted. The law should have adequate safeguards to prevent its misuse.

- Each agency should be identified as part of the SWOT analysis and thereafter the Counter strategy should have a coordinating and representative presence of each agency at the policy making and enforcement level

- Government should overhaul their entire approach to combat terror-financing, shift their focus away from the financial sector and link it to a broader strategy that includes military, political and law enforcement measures.

- The international community and organisations, including the FATF, should keep up the pressure until Islamabad shows tangible outcomes.

Background

Financial Action Task Force

- The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is an inter-governmental body established in 1989 during the G7 Summit in Paris.

- The objectives of the FATF are to set standards and promote effective implementation of legal, regulatory and operational measures for combating money laundering, terrorist financing and other related threats to the integrity of the international financial system.

- Its Secretariat is located at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) headquarters in Paris.

- Member Countries: it consists of thirty-seven member jurisdictions.

- India is one of the members.

- FATF has two lists:

- Grey List: Countries that are considered safe haven for supporting terror funding and money laundering are put in the FATF grey list. This inclusion serves as a warning to the country that it may enter the blacklist.

- Black List: Countries known as Non-Cooperative Countries or Territories (NCCTs) are put in the blacklist. These countries support terror funding and money laundering activities. The FATF revises the blacklist regularly, adding or deleting entries.

- The FATF Plenary is the decision making body of the FATF. It meets three times per year.

NO MINISTER, THE TRADE AGREEMENT PITCH IS FLAWED

Context:

India’s External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar has presented an ill-considered take on India’s trade record in a ‘keynote’ speech delivered at a “dialogue” on November 16.

Relevance:

GS Paper 3: Effects of Liberalisation on the economy; Changes in Industrial policy & their effects on industrial growth.

Mains Questions:

- Domestic demand is assuming primacy over export-orientation and trade restrictions are increasing, reversing a 3-decade trend. Comment 15 marks

- Examine the impact of liberalization on companies owned by Indian. Are the competing with the MNCs satisfactorily? 15 marks

Dimensions of the Article

- What is Globalization?

- Three Myths of the Globalization

- Has India been turning Inward?

- Dispelling the myths

- Conclusion

What is Globalization?

Globalisation is the process by which the world is becoming increasingly interconnected as a result of a huge growth in trade and cultural exchange. Globalisation has increased the production of goods and services. Globalisation has resulted in:

- Increased international trade.

- The same company operating in more than one country

- A greater dependence on the global economy

- Easier movement of capital, goods and services.

- Recognition of companies such as McDonalds and Starbucks in developing countries.

Three Myths of the Globalization

- The first is that India’s domestic market is large and buoyant: In fact, the domestic market is still quite small, and likely to remain small over the medium-term, since domestic demand will be weighed down by heavy debts across the economic horizon—in firms, households, and the government.

- The second myth is that India’s growth has been driven by domestic demand, not by exports, and definitely not manufacturing exports: The evidence illustrates the opposite, namely that for three decades a stellar export performance has played a critical role in India’s overall growth.

- The third myth is that India’s exports prospects are dim: The evidences show to the contrary, that India has considerable room to increase exports by increasing its market share. India has been gaining market share for several decades now, even during the difficult global conditions of the past decade. Moreover, India’s past under-performance on low-skill exports creates a significant opportunity at a time when China is vacating export space in such products.

Has India been turning Inward?

Inward and outward orientation can be assessed on a number of dimensions: macroeconomic, trade, capital flows, people, technology and data. We will restrict ourselves to the first two, where the inward turn is more pronounced.

Macro-economic

Inward orientation has become central to India’s policy and intellectual discourse. A consensus seems to be emerging that India’s growth slowdown pre-Covid owed to weakening domestic demand, especially consumption. Accordingly, there has been a search for policies to revive demand, with some proposing a redistribution of income, others suggesting agricultural reforms, and still others proposing more public investment.

Trade

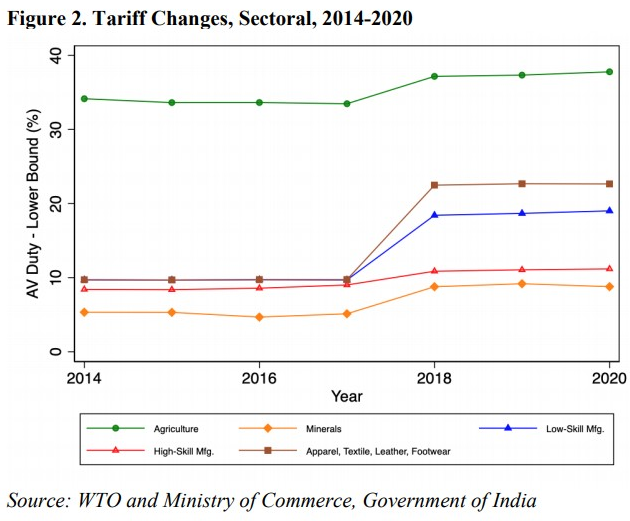

The inward orientation on trade is discernible in actual policies. Tariffs have been raised, free trade agreements have been put on hold (and a major Asian treaty rejected), and production subsidies have been rolled out. The inward turn marks a major break with the three-decade trend of steady opening since 1991.

Dispelling the myths

Myth 1: Growth can be based on the domestic market because it is big

Underlying the India-is-big view are three claims:

- First, a large domestic market increases the scope for import substitution: when domestic demand is large, it makes sense for firms to set up factories in India, rather than supply from abroad.

- Second, it makes sense to use India as a global export base, since the large population means that there is a large labour force that can be tapped. In particular, India’s large population, combined with financial assistance (zero input tariffs, production and other subsidies), could lure firms that are now exiting China for geo-political reasons. After all, India is the only other country in the world with a population size comparable to China.

- Third, with a large market, India—like the US and China—can create national champions in the new technology and technology-intensive sectors. This can be done through restricting competition, domestic and foreign, as well as through domestic regulatory assistance.

However, The “true” market is:

- A fraction of the headline GDP number, somewhere between 15 and 45 percent of GDP

- Much smaller than China’s, roughly 15-20 percent of China’s true market size; and

- A tiny 1½-5 percent of the global market.

Myth 2: India’s growth has not been driven by exports and certainly not manufacturing exports

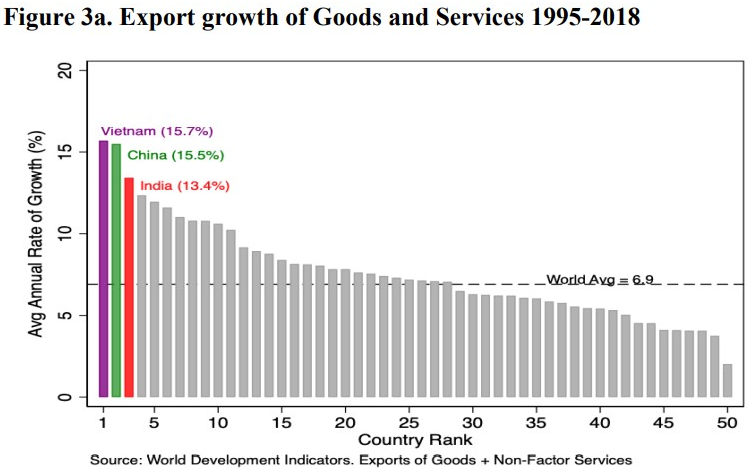

For the three decades since the early 1990s India has been an exemplar of export-led growth, not only in services but also in manufacturing. Its export growth has been positively East Asian Tiger, which in turn has driven and/or sustained high GDP growth.

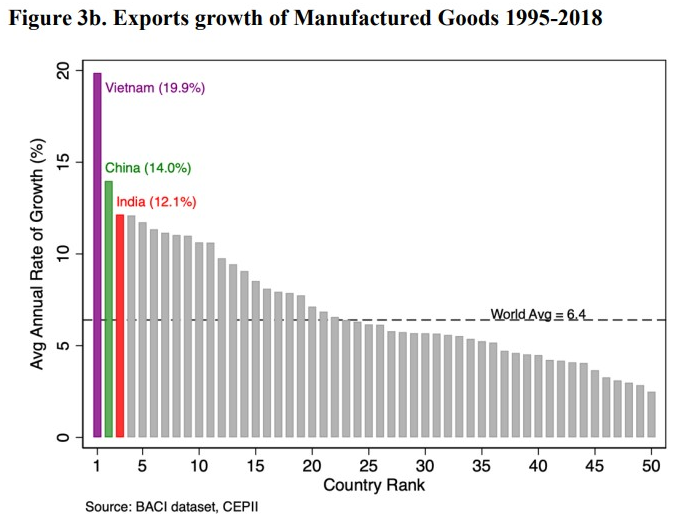

Moreover, this is not just because India is a services export powerhouse but also because it is a successful exporter of manufacturing products. Over the same period, India’s manufacturing exports (in dollars)—long considered to be the country’s Achilles’ Heel—grew on average by 12.1 percent, nearly twice the world average. This was the third-best performance in the world, surpassed only by China and Vietnam.

Myth 3: Export-led growth is not possible in the post-Covid world

Some advocates of inward orientation argue that even if India’s exports have done well in the past, the future is going to be different. In particular, export growth will inevitably be slow in a postCovid world. After all, global export growth decelerated from 15 percent to 5 percent after the GFC, and things will surely become worse post-COVID as countries consider the risks arising from dependence on imports, at least for essential commodities such as food and medicines. At the same time, domestic export capability has diminished, as shown by India’s inability to take advantage of the big opportunity created by China’s vacating of export space over the past decade. Thus, supply and demand considerations support turning inward to find our own market to support our growth. However, These arguments can be countered through followings facts:

A. India-friendly upside to globalization post-Covid

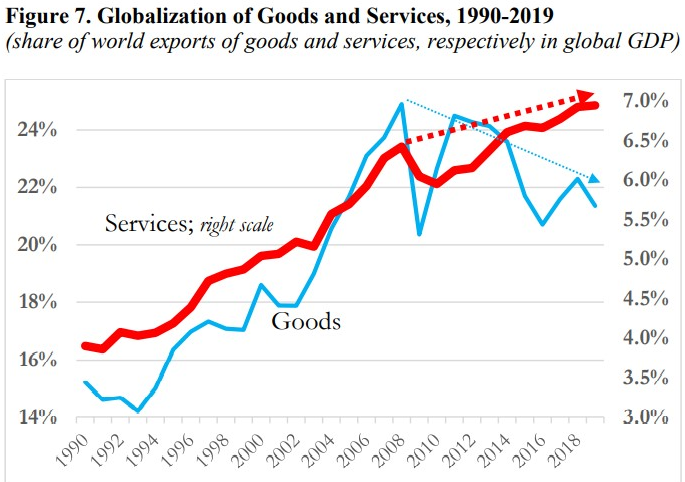

The reports of globalisation’s demise have been greatly exaggerated. It is true that world exports of goods have declined to about 21 percent of world GDP from about 25 percent prior to the GFC. But world exports of services have continued to increase, rising to about 7 percent of global GDP from 6.5 percent prior to the GFC. In other words, the globalization of services is continuing.

What are the prospects for services exports post-Covid? Quite possibly, the trend might actually accelerate. After all, the pandemic is encouraging activities that can be done at a distance, as opposed to those that require physical contact. For example, physical shops are being replaced by websites—which could be designed and serviced in India. Similarly, if firms in the West are going to allow employees to work permanently from home, these employees could just as easily—and more cheaply—be located in India.

India might even benefit from post-Covid trends in the production of goods. The pandemic has highlighted the risks of depending entirely on one country for provisions of key goods; in the future, there will be a concerted effort to diversify the sources of supply. And India could be a major beneficiary of this search for new, low-cost suppliers.

B. Gaining market share even in a deglobalizing world

But even on the assumption that globalization in goods comes to a halt post-Covid, the export outlook would still remain far from bleak—because India could continue to gain market share. Often, this possibility is dismissed, on the grounds that: “yes, Vietnam could do it but India is not Vietnam; it is too big.” But in this argument is not well-founded. In fact, India is not a big exporter on the global scale; its share of global manufacturing exports is only 1.7 percent, marginally less than Vietnam’s at 1.75 percent (Table 3). So on the relevant metric India is not big, compared to Vietnam.

C. India’s big unexploited opportunity of unskilled labor exports

India’s share of global labor force far exceeds its share of low-skill exports. For China, it is exactly the reverse. India’s share of global low-skilled exports is about 15 percentage points less than its share of the labor force. The implication is that India is exporting about $60 billion of low-skill exports annually less than it should be.

If China as producer can contribute by vacating export space, China as consumer could become a bigger market for low-skill consumer goods. In effect, China would do for poorer countries what the West did for China—providing a ready market for its goods. This, of course, would require China to become more open and less protectionist at least for low-skill goods.

Evaluating the twin prescriptions

Domestic demand over exports

- Foreign demand will always be bigger than domestic demand for any country.

- There is a fundamental asymmetry in that if domestic producers are competitive internationally, they will be competitive domestically and domestic consumption will also benefit.

- Investment will be constrained, because after the long lockdown most firms aren’t in any financial position to embark on new projects, while those that are financially strong will find it difficult to secure funding because the banking system is struggling under the weight of large nonperforming assets.

- The climate for risk-taking has also been seriously undermined given the concerns about the hyper activism of India’s investigative agencies (the famous 4 Cs: Courts, CBI, CVC and CAG).

- Consumption going forward will be limited by the fact that household debt has grown rapidly in the last few years. Most importantly, consumption will thus depend on income, not the other way around.

- Government spending will be severely circumscribed over the medium-term. Already this year the pandemic has pushed the overall deficit (centre and states) well into the double-digit range, while propelling debt from about 70 percent of GDP to about 85-90 percent.

Protectionism over freer trade:

- Export performance was weak under the protectionist license-quota-raj. But after the economy was liberalized, exports boomed. Real export growth of goods and services averaged close to 11 percent between 1992 and 2019, more than double the 4.5 percent rate recorded between 1952 and 1991. And overall GDP growth rates were 6.5 percent and 3.5 percent, respectively in these two periods.

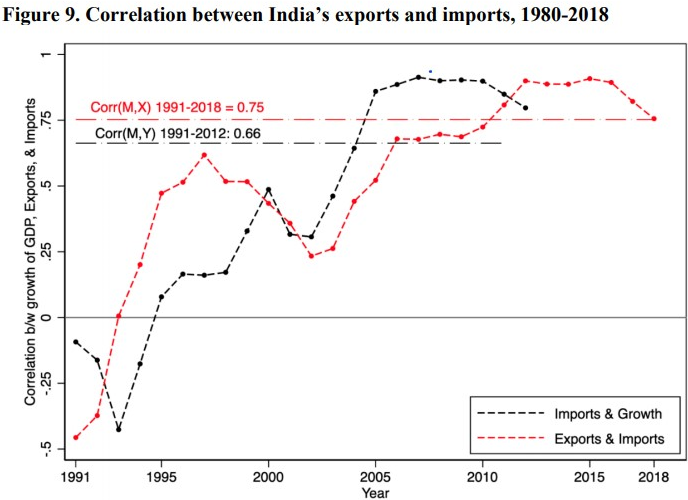

- The association of India’s export boom with liberalization is not just a coincidence. India’s exports have required imports to sustain them. The exports have been highly correlated with imports (correlation co-efficient of 0.75). Moreover, The growth has been highly correlated with imports, suggesting that openness is needed for growth.

Conclusion

The conclusion is clear. Resisting the misleading allure of the domestic market, India should zealously boost export performance and deploy all means to achieve that. Pursuing rapid export growth in manufacturing and services should be an obsession with self-evident justification. Abandoning export orientation will amount to killing the goose that lays golden eggs and indeed to killing the only goose laying eggs. Alas, to embrace Atmanirbhar is to choose to condemn the Indian economy to mediocrity.