Contents

- Economics behind India’s GDP Growth Contraction

- How public policy in social media works?

ECONOMICS BEHIND INDIA’S GDP GROWTH CONTRACTION

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Introduction

- The collapse of gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 23.9% for the April to June period comes as an expectation given that the economy was under a strict lockdown for most of the time to contain the pandemic.

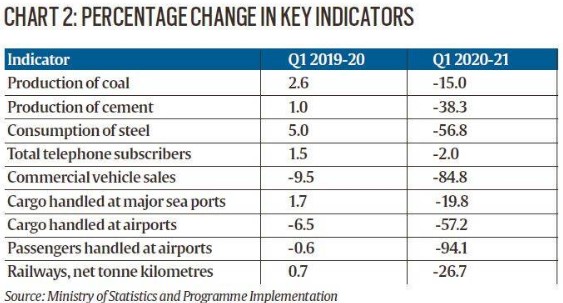

- Almost all the major indicators of growth in the economy — be it production of cement or consumption of steel — show deep contraction.

What does the GDP figure highlight?

- In Q1FY21, private consumption expenditure contracted by 26.7% and investment by 47.1%.

- With physical mobility limited, discretionary spending took a back seat, and the situation became worse as incomes fell.

- With migrant workers heading home, infrastructure projects were thrown out of gear, causing a huge contraction in investment.

- It should be noted that private consumption and investment are two major contributors to the GDP.

How did government expenditure fare?

- In recent years, government expenditure has formed 8-13% of the overall economy (the GDP).

- From April to June 2020, it reached at around 18.1% of the GDP, the highest in more than 19 years.

- This additional expenditure essentially ensured lower contraction of the economy.

- If we leave the government expenditure out of the calculation, what we are left with is the non-government part of the economy, which is the major part of the economy. This contracted by a massive 29.3%, much more than the overall economy.

What is biggest implication?

- With GDP contracting by more than what most observers expected, it is now believed that the full-year GDP could also worsen.

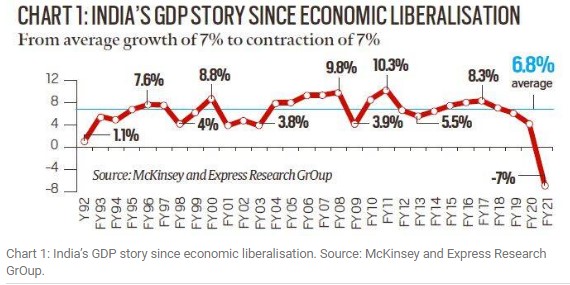

- Since economic liberalisation in the early 1990s, Indian economy has clocked an average of 7% GDP growth each year. This year, it is likely to turn turtle and contract by 7%.

- In terms of the gross value added (a proxy for production and incomes) by different sectors of the economy, data show that barring agriculture, where GVA grew by 3.4%, all other sectors of the economy saw their incomes fall.

How different Sectors fared?

- The worst affected were construction (–50%), trade, hotels and other services (–47%), manufacturing (–39%), and mining (–23%).

- It is important to note that these are the sectors that create the maximum new jobs in the country.

- In a scenario where each of these sectors is contracting so sharply — that is, their output and incomes are falling — it would lead to more and more people either losing jobs (decline in employment) or failing to get one (rise in unemployment).

What caused GDP contraction?

- In any economy, the total demand for goods and services — that is the GDP — is generated from one of the four engines of growth. The biggest engine is consumption demand from private individuals (In the Indian economy, this accounted for 56.4% of all GDP before this quarter).

- The second biggest engine is the demand generated by private sector businesses (This accounted for 32% of all GDP in India).

- The third engine is the demand for goods and services generated by the government (It accounted for 11% of India’s GDP).

- The last engine is the net demand on GDP after we subtract imports from India’s exports (In India’s case, it is the smallest engine and, since India typically imports more than it exports, its effect is negative on the GDP).

- So total GDP = C + I + G + N (Where C= Consumption from Private Individuals, I = Private Sector Businesses, G= Goods and Services Generated by the Government, and X= Net demand on GDP after we subtract imports from India’s exports).

In the Current Scenario:

- Private consumption — the biggest engine driving the Indian economy — has fallen by 27%.

- The second biggest engine — investments by businesses — has fallen even harder to half of what it was in the same quarter of 2019.

- So, the two biggest engines, which accounted for over 88% of Indian total GDP, Q1 saw a massive contraction.

The net result is that while, on paper, government expenditure’s share in the GDP has gone up from 11% to 18% yet the reality is that the overall GDP has declined by 24%.

It is the lower level of absolute GDP that is making the government look like a bigger engine of growth than what it is.

What is the way out?

- When incomes fall sharply, private individuals cut back consumption. When private consumption falls sharply, businesses stop investing.

- Since both of these are voluntary decisions, there is no way to force people to spend more and/or coerce businesses to invest more in the current scenario.

- The same logic holds for exports and imports as well.

- Under the circumstances, there is only one engine that can boost GDP and that is the government (G).

- Only when government spend more — either by building roads and bridges and paying salaries or by directly handing out money — can the economy revive in the short to medium term.

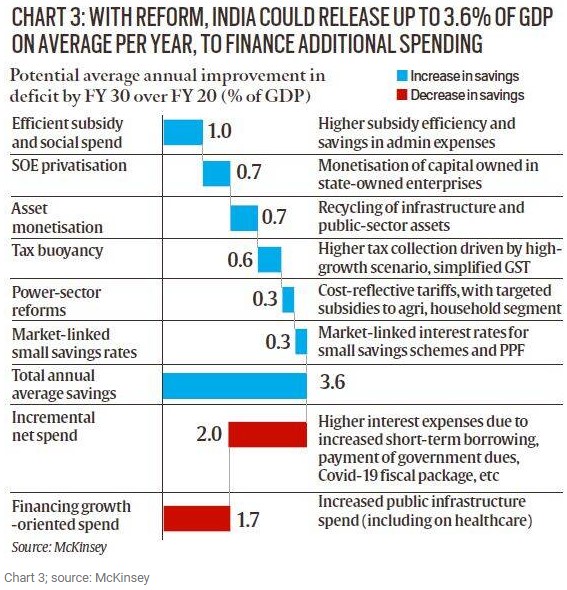

What is holding back the government from spending more?

- Even before the Covid crisis, government finances were overextended. In other words, it was not only borrowing but borrowing more than what it should have. As a result, today it doesn’t have as much money.

- It will have to think of some innovative solutions to generate resources.

-Source: Indian Express, Livemint

HOW PUBLIC POLICY IN SOCIAL MEDIA WORKS?

Focus: GS-II Governance

Introduction

- Last week, a committee of the Delhi Legislative Assembly took up Facebook’s alleged “inaction” due to reports that a top executive of Facebook in India had “opposed applying hate-speech rules” to users linked to the ruling party, citing business imperatives.

- Facebook has been accused of bias, of not doing enough to discourage hate speech, and of letting governments influence content decisions on the platform.

History of the debate

- Back in 2009, when Facebook had only 200 million users (fewer than its current user base in India), critics noticed Holocaust deniers on the platform – and German prosecutors launched an investigation against the company’s local head executive for abetment of violent speech.

- In the run-up to the 2016 presidential election in the United States, Facebook allowed videos posted by then candidate Donald Trump that violated their guidelines, saying the content was “an important part of the conversation around who the next US President will be”.

- In 2018, Facebook admitted to having failed to prevent human rights abuses on the platform in Myanmar.

Regulations in place

- Internet regulations in several countries (including India’s Section 66A of The Information Technology Act) protect platforms from having immediate liability for content, ostensibly to guard against over-censoring.

- Because of rising frustrations, however, governments are threatening those legal protections.

How content moderation works

- The vast majority of content on Facebook is flagged by an algorithm if it violates company rules.

- Users can manually flag content, which gets directed to content moderators sitting in contracted offices all over the world.

- If the content comes to these Facebook employees in a team called ‘Strategic Response’, they can rope in other local teams.

- Public policy is often involved if there are certain sensitive risk factors, such as political risk, that need to be considered.

- If internal groups disagree, the decision is escalated, potentially all the way up to Zuckerberg himself.

The situation in India

- The Wall Street Journal report said Facebook’s top public policy executive in India cited government-business relations to not apply hate-speech rules to certain individuals and groups liked to a particular party which are internally flagged for violent speech.

- The report’s findings on a “pattern of favoritism” towards the party calls into question the personal political leanings of company officials, and their ability to dominate content deliberations in these processes.

- Some technology policy experts have called for a thick line between public policy and content moderation, while others have criticised the processes as “informal and opaque”.

- Traditionally, public policy roles have entailed government relations. This model doesn’t extend itself well to social platforms though.

- There is an inherent conflict when government relations and policy enforcement go to the same set of people or organisation units.

- The real concern is the lack of public transparency and insufficient internal accountability in decision-making when it comes to content moderation.

- The problem in the recent revelations regarding Facebook India is public policy teams having the apparent ability to veto or block these decisions based exclusively on business considerations.

The platforms are reacting by self-regulating in a manner that imperils free expression while failing to truly address the problem of hyper-local harmful speech.

What is the Information Technology (IT) Act?

- The Information Technology Act, 2000 is the primary law in India dealing with cybercrime and electronic commerce.

- The laws apply to the whole of India. If a crime involves a computer or network located in India, persons of other nationalities can also be indicted under the law.

- The Aim of the Act was to provide legal infrastructure for e-commerce in India.

- The Information Technology Act, 2000 also aims to provide for the legal framework so that legal sanctity is accorded to all electronic records and other activities carried out by electronic means.

- It also defines cyber-crimes and prescribes penalties for them.

Section 66A of IT Act – Struck down

- Section 66A of the IT Act has been enacted to regulate the social media law India and assumes importance as it controls and regulates all the legal issues related to social media law India.

- This section clearly restricts the transmission, posting of messages, mails, comments which can be offensive or unwarranted.

- The offending message can be in form of text, image, audio, video or any other electronic record which is capable of being transmitted.

- In the current scenarios such sweeping powers under the IT Act provides a tool in the hands of the Government to curb the misuse of the Social Media Law India in any form.

- However, in 2015, in a landmark judgment upholding the right to free speech in recent times, the Supreme Court in Shreya Singhal and Ors. Vs Union of India, struck down Section 66A of the Information & Technology Act, 2000.

- The judgment had found that Section 66A was contrary to both Articles 19 (free speech) and 21 (right to life) of the Constitution.

- The repeal of 66A does not however result in an unrestricted right to free speech since analogous provisions of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) will continue to apply to social media online.

-Source: Indian Express, Livemint