Contents

- In Assam, a trail of broken barriers

- Diluting the EIA process

IN ASSAM, A TRAIL OF BROKEN BARRIERS

Focus: GS-III Disaster Management

Introduction

- The Hajong community was settled in Dhamor Reserve as refugees from erstwhile East Pakistan in 1960s and each family has an average of three bighas of land for farming.

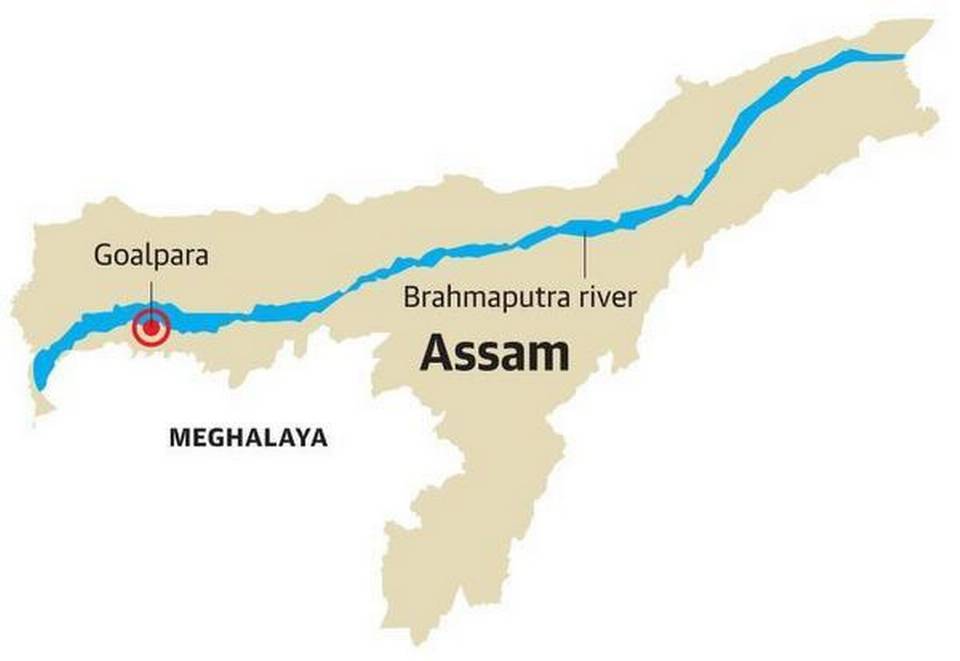

- Goalpara saw flash floods earlier, but in the eastern part bordering the North Garo Hills district of Meghalaya in areas along three tributaries of the Brahmaputra.

- The devastation this time came to the western part following a cloudburst in Meghalaya’s West Garo Hills.

Dykes and issues

- The Assam’s Water Resources Department (WRD) manages two Brahmaputra dykes in Goalpara district.

- According to WRD officials, newly constructed barriers to keep rivers in check are embankments while the older ones needing repairs and periodic maintenance are dykes.

- The plight of relief workers and service providers is no different from the inmates of the camps.

- All of them had raised their houses after the 1998 flood level they thought would be difficult to surpass.

Blame it on the embankments

- Data provided by the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) say 220 embankments were damaged or breached this time.

- The intensity, damage and death in the last two decades have been proportional to the breaching of embankments, and it is getting worse every year.

- This also indicates how the entire flood management is heavily dependent on ad hoc embankments.

- Planners and engineers laid the “foundation of disaster” with the dyke-oriented National Policy for Flood four years after the great earthquake of 1950 that affected the courses of some major rivers.

- No time, energy or resources were spent on studying the hydrological, geo-morphological and climatic conditions of the rivers as the embankments came up all over.

- The embankments outlived their utility and began collapsing from the 1990s, rapidly by the turn of the millennium.

- There was patchwork maintenance of the old dykes, and agencies other than the WRD began building embankments haphazardly without any scientific input.

- The problematic embankments are usually the ones done locally without adhering to certain specifications and not maintained.

Other system worsening the case

- The Brahmaputra Board, formed in 1980 to “integrate management of flood and basins of interstate and international rivers in the northeast”, came up with the idea of building big storage dams to contain the rivers upstream.

- High-volume discharge of water from hydropower dams in Arunachal Pradesh and Bhutan during the monsoon season has added to Assam’s flood problems.

- Many don’t have a clue about the fast-changing moods of the Brahmaputra and its tributaries, leading to the desertification of large swathes of hitherto fertile flood plains.

- Hydrologists point out that while the emphasis has been on building dyke after dyke, often to save one from the other, no thought has been given to how to properly drain water from the floodplains.

Moving things in the right direction

- There are discussions about inter-departmental synergy in handling conventional methods of flood mitigation.

- Officials say they have been focussing on research and development in addition to execution of flood management work and collection of hydro-meteorological data.

- The conversion of a River Research Station of 1958 vintage to the Assam Water Research and Management Institute is an example, as are activities such as geo-technical exploration and investigation, hydrological modelling, physical identification of soil samples and grain size analysis.

-Source: The Hindu

DILUTING THE EIA PROCESS

Focus: GS-III Environment and Ecology

Introduction

- Around the world, legislative interventions mandating EIAs began to burgeon in the late 1960s.

- The basic credo of these measures was to ensure that the state had at its possession a disinterested analysis of any development project and the potential impact that it might have on the environment.

- It took India, though, until 1994 before it notified its first set of assessment norms, under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986.

- This policy mandated that projects beyond a certain size from certain sectors — such as mining, thermal power plants, ports, airports and atomic energy — secure an environmental clearance as a precondition to their commencement.

- But the notification, subject as it was to regular amendments, proved a failure.

Abandoning rigour

The 2006 EIA increased the number of projects that required an environmental clearance, but also created appraisal committees at the level of both the Centre and States, the recommendations of which were made a qualification for a sanctioning and the programme also mandated that pollution control boards hold a public hearing to glean the concerns of those living around the site of a project.

In practice, the 2006 notification also proved regressive

- The final EIA report was not made available to the public

- The procedure for securing clearances for certain kinds of projects was accelerated

- There was little scope available for independent judicial review.

Concerns with the 2020 notification

- It enables a sweeping clearance apparatus to a number of critical projects that previously required an EIA of special rigour; where some industries require expert appraisal under the existing 2006 notification, they will, under the new notification, be subject to less demanding processes.

- These include aerial ropeways, metallurgical industries, and a raft of irrigation projects, among others.

- The new proposal does nothing to strengthen the expert appraisal committees on which so much responsibility is reposed, leaving the body rudderless.

- It also does away with the need for public consultation for a slew of different sectors, negating perhaps a redeeming feature of the 2006 notification.

- If there is a singular logic to the EIA process, it is that an environmental clearance is a prerequisite to the launching of a project.

Conclusion

We need a renewed vision for the country; one that sees the protection of the environment as not merely a value unto itself but as something even more foundational to our democracy.

-Source: The Hindu