Contents:

- A duty to publish: On RTI

- Relevance of Death Sentence

- Is India facing Stagflation

A duty to publish: On RTI

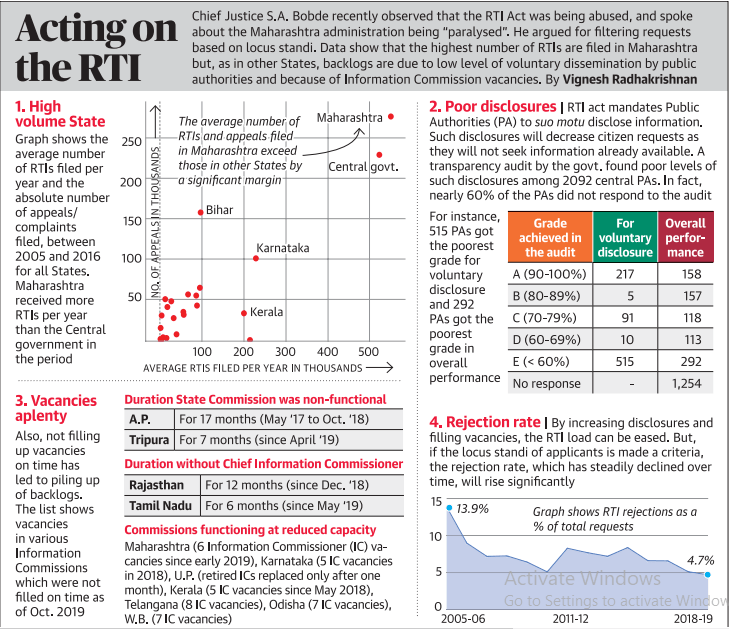

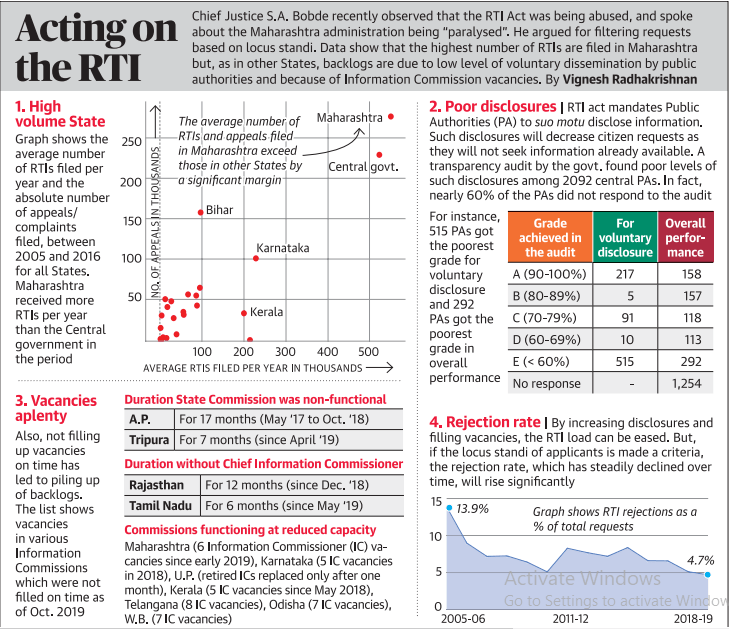

The Right to Information Act’s role in fostering transparency has never been in doubt ever since its roll out in 2005. Section 4 of the Act calls for proactive and voluntary dissemination of information

But only a few Central and State institutions have published relevant information. In this, Rajasthan has taken a lead through its Jan Soochna portal.

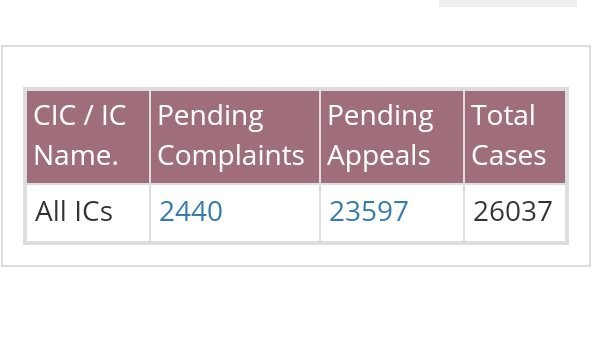

The other problem has been persisting vacancies in the State and Central Information Commissions and around 33,000 pending cases.

What the SC has said?

The Supreme Court has paid heed to the problem and asked the Centre and States to expedite filling up the vacancies.

- The CJI also curiously observed that officials were sensing fear leading to paralysis of action due to the working of the RTI.

- The kind of queries that were sometimes being asked were not always in public spirit and were posed by people who had no “locus standi” in the matter regarding the queries.

SC’s mistake

This argument by the CJI is difficult to accept as the RTI Act explicitly rejects the need for locus standi in Section 6(2) “an applicant making request for information shall not be required to give any reason for requesting the information.

Why ‘Locus standi’ should not be a criterion

Since 2005 yearly rejection rate (requests rejected as a percentage of those received) has come down steadily to 4.7% in 2018-19. A change in the Act that seeks locus standi as a criterion could dramatically increase this number.

Rather than focusing on locus standi, public authorities would be advised to provide for greater voluntary dissemination on government portals, which should ease their load.

Extra Coverage:

Chipping away power of RTI in the past:

The new rules of RTI Act based on July 2019 amendments to the 2005 Right to Information Act downgraded the office of the chief and other information commissioners at the Centre and in the states.

Parity with CEC broken – So far the CIC received the same salary and perks as that of the Chief Election Commissioner or a judge of the Supreme Court.

Now on par with Cabinet Secretary – The new rules make the CIC an equivalent of the cabinet secretary and central information commissioners the same as secretary to the government in terms of salary. In the states, the downgrading will be to the level of a secretary to the government, and additional secretary respectively.

Tenure – The tenure has been reduced from 5 years to 3.

Tampered appointments – Appointments to the posts have been used to grant sinecures to favoured retired bureaucrats or dispense favours to camp-followers.

Poor strength – There has been an enormous reluctance in many states to appoint the full strength of commissioners, leading to a large pendency.

Rejection of requests – The CIC returns a large number of complaints and appeals on minor grounds. Still, the RTI Act helped ordinary citizens feel empowered to take on corruption.

One-sided transparency – what the government wants to put out is rarely matched with what citizens want to know about its decisions.

RELEVANCE OF DEATH SENTENCE.

Why in news?

Supreme Court dismissed review petitions by all four convicts in the Nirbhaya rape and murder case.

It is clear that death penalty as a measure to end sexual violence has completely failed. In 1965, only 23 nations had abolished the death penalty. But, subsequently, criminal justice systems across the world lost confidence in this mode of punishment. Today, over two thirds of countries have given up on capital punishment

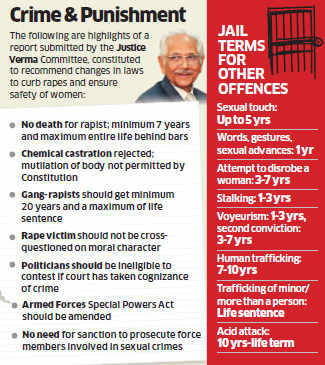

J.S. Verma Committee said that capital punishment is a regressive step and may not provide deterrence. The committee recommended the life sentence for the most grievous of crimes.

Against natural justice

In the system of criminal justice worldwide, including in India, underpinning the element of sentencing is the ‘Theory of Punishment’.

It stipulates that there should be four elements of a systematic punishment imposed by the state:

1. the protection of society;

2. the deterrence of criminality;

3. the rehabilitation and reform of the criminal; and

4. the retributive effect for the victims and society.

Capital punishment, in its very essence, goes against the spirit of the ‘Theory of Punishment’, and by extension, natural justice.

How capitail punishment goes against the Principle of Natural justice

- The first element, ‘protection of society,’ is not served by imposing the death sentence any better than by incarceration. This has been proven time and again as inmates have spent decades on death row, harming no one, but being brutalised by the inhuman punishment meted out to them.

- Second, there are several factors which affect criminal activity and deterrence is only one of them.

- In a UN survey, it was concluded that “capital punishment deters murder to a marginally greater extent than the threat of life imprisonment.”

- It is not just statistics that prove the case against deterrence, so does logic. A reasonable man is deterred not by the gravity of the sentence but by the detectability of the crime.

- Third, the facet of ‘reform and rehabilitation of the criminal’ is immediately nullified by the prospect of capital punishment

- This leaves only the final element — ‘the retributive effect’. Killing should never be carried out based on the primal and emotive desire among human beings for revenge. Revenge is a personalised and emotional form of retribution, which often loses sight of proportionality.

Poor and the deprived

Justice P.N. Bhagwati, said that “death penalty in its actual operation is discriminatory for it strikes mostly against the poor and deprived”. The reasons include lack of adequate legal assistance to the marginalised.

Recent incidents of heinous violence perpetrated against women, it becomes imperative for the judiciary not give in to the public clamour for making capital punishment mandatory for rape convicts

There needs to be better enforcement of law in response to valid questions on justice but death penalty holds no answers.

Is India facing stagflation?

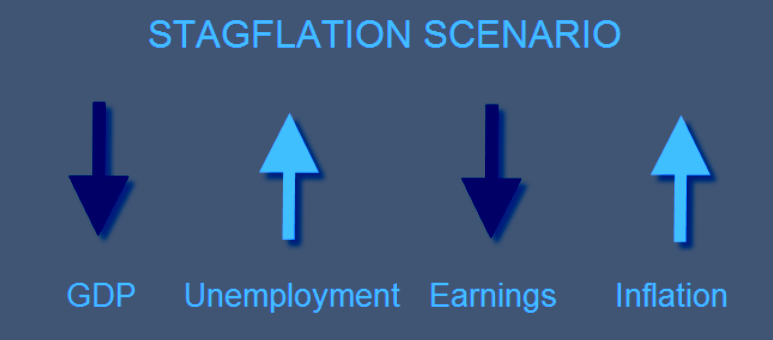

What is Stagflation?

Simply put, Stagflation is a combination of stagnant growth and rising inflation. Typically, inflation rises when the economy is growing fast. That’s because people are earning more and more money and are capable of paying higher prices for the same quantity of goods. When the economy stalls, inflation tends to dip as well – again because there is less money now chasing the same quantity of goods.

Stagflation is said to happen when an economy faces stagnant

growth as well as persistently high inflation. In other words, the worst of

both worlds. That’s because with stalled economic growth, unemployment tends to

rise and existing incomes do not rise fast enough and yet, people have to

contend with rising inflation. So people find themselves pressurised from both

sides as their purchasing power is reduced.

India’s GDP numbers of second quarter released, here’s how to read them

Has it happened in the past?

Most famous case of stagflation happened in the early and mid-1970s when OPEC (The Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries), which works like a cartel, decided to cut supply and sent oil prices soaring across the world.

On the one hand, the rise in oil prices constrained the productive capacity of most western economies that heavily depended on oil, thus hampering economic growth. On the other hand, the oil price spike also led to inflation and commodities became more costly.

The net result was lower growth, higher unemployment, and higher price level. That’s stagflation.

So, is India facing Stagflation?

India is not yet facing stagflation. There are three broad reasons for it.

One, India is still growing at 5% and is expected to grow faster in the coming years. India’s growth hasn’t yet stalled and declined; in other words, year on year, our GDP has grown in absolute number, not declined.

Two, it is true that retail inflation has been quite high in the past few months, yet the reason for this spike is temporary because it has been caused by a spurt in agricultural commodities after some unseasonal rains. With better food management, food inflation is expected to come down. The core inflation – that is inflation without taking into account food and fuel – is still benign.

Lastly, retail inflation has been well within the RBI’s target level of 4% for most of the year. A sudden spike of a few months, which is likely to flatten out in the next few months, it is still early days before one claims that India has stagflation.