Contents

- Short on labourers, a long harvest

- A season of change: Meteorological department

- A virus, social democracy, and dividends for Kerala

- Why gold prices have been rising before and during COVID-19?

SHORT ON LABOURERS, A LONG HARVEST

Focus: GS-III Agriculture

Lockdown’s Impact on Harvesting

- Usually, 90% of the wheat in Punjab and neighbouring Haryana is harvested using combine harvester machines. But with physical distancing norms in place now, for many small farmers, that system has been thrown out of gear as they can’t jointly hire the machine and the produce must be brought to the mandis through commission agents so that people don’t congregate.

- The major worry is how to store this harvested produce during this extended period.

- Unfortunately the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) forecast says a western disturbance is likely to affect the western Himalayan region, which could bring scattered rain and thunder showers over the region on April 17 and 18. Standing crops and harvest stored in the open could face widespread damage.

- The problem may be more acute for those selling perishable crops such as fruits and vegetables.

- The government in its initial order did not specify fruit transport as an essential service. There was confusion. It led to the destruction of fruit crop all over Maharashtra.

- The impact of this virus is much bigger than any drought.

Wheat harvest in India during these tough times in different regions

- Wheat is the major rabi crop in the winter farming season in India, and the only one bought by government agencies at the pre-set minimum support price (MSP).

- In western States such as Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and even Rajasthan, warmer weather means that the wheat harvest was already under way when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country, and is now largely over.

- However, the bulk of the country’s wheat is grown in Punjab and Haryana, an area known as the bread basket of India. The prolonged winter delayed the maturing of the grain and pushed harvesting dates by at least a week.

- Punjab is expecting a bumper wheat harvest crop this season with production likely to touch 182 lakh tonnes.

- The cash credit limit of ₹22,900 crore has already been approved by the Centre to ensure prompt and seamless procurement operations in the State.

What is being done to help?

- The long list was presented to the States, via video conferencing due to the lockdown, along with another long list of actions taken by the Centre to facilitate agricultural activity.

- All agricultural work was exempted from lockdown restrictions.

- Mandis can function with at least 50% of their workforce. Although migrant labour may have left, local labour is available, so there is no need to panic. Anyway, most Punjabi farmers use machines for harvesting.

- To ensure that farmers get their monetary return at the earliest, the amendment of the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) Act has been notified to ensure that farmers are paid electronically through commission agents within 48 hours after the produce is lifted.

The coupon system

- With each coupon a farmer will be entitled to bring one trolley of about 50 to 70 quintals of wheat.

- A farmer will be entitled to take multiple coupons each day or on different days depending on space in the purchase centre in order to avoid rush in the mandis.

- As one coupon only allows sale of 50 quintals, it will be a difficult task for farmers with big landholdings to sell their produce.

- Once a farmer uses up the given coupon, until the next coupon is given, the harvest will be out in the open due to lack of storage facilities and face risks. Also, fire incidents during the harvesting season usually go up, which is a major concern for crop safety.

The policy-implementation gap

- The Centre announced a slew of relaxations and support measures for agriculture in the first two weeks of the lockdown.

- All agricultural and horticultural activities, markets, labour and transport were supposed to be exempt from lockdown restrictions.

- Subsidies on crop loans were extended for late repayment. States were asked to relax regulations and allow direct purchases by bulk buyers and retailers.

- The digitally connected e-NAM marketplace system was touted, along with a logistics module connecting farmers and traders to a network of almost 8 lakh trucks and 2 lakh transporters.

- The Railways introduced 67 routes for perishable produce. An “Agri-Transport” Call Centre was set up to handle transport issues.

- However, as farmers from different parts of the country reported, many of these policies were not uniformly implemented on the ground, especially in the first few weeks.

- In many cases, the Centre’s instructions have not percolated down to District Magistrates and Superintendents of Police, resulting in the harassment of farmers and agricultural traders, and supply chain disruptions

Conclusion

- The lockdown has proved one thing: agriculture is truly the backbone of the Indian economy. Coronavirus or not, farm production goes on because the demand for food will always be there.

- But the cost to the farmer, to agricultural workers, is not taken into account in that process.

- Also, this reverse migration proves that they were actually agricultural refugees, who left for the cities only because they could not make a living in the fields

- Everyone is talking about the need to invest in public health once the COVID-19 crisis is over. Our farmers, agricultural workers are also front line workers during this time and they also deserve attention. If we can invest in agriculture and overhaul it so it is profitable, then we will have actually learned something from this crisis.

A SEASON OF CHANGE: METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT

Focus: GS-III Science and Technology, GS-I Geography

IMD’s Monsoon Forecast

- In the season of the abnormal, the IMD has announced that the monsoon this year would likely be normal.

- The agency follows a two-stage forecast system: indicating in April whether there are chances of drought or any other anomaly and then a second update, in late June, with a more granular look at how the monsoon will likely distribute over the country and whether danger signs are imminent.

- ‘Normal’ means India will get 100% of its long period average, with a potential 5% error margin.

Unpredictability

- In April last year, it said the monsoon would be ‘near normal’, an arbitrary category. Private forecasters expected a shortfall, predicated on the development of a future El Niño. The IMD did account for this but said it was unlikely El Niño would strengthen enough to dampen the monsoon. It however kept its estimate on the lower side of ‘normal.’

- In the end, India received excess rains, the highest in a quarter century.

Lagging behind with the times

- The April forecast is a vestige of the agency’s reliance on the ‘statistical forecast system’ where values of selected meteorological parameters are recorded until March 31 and permutations of these are computed and compared to the IMD’s archive of weather data. It is also reflective of an era when landline telephones were the state-of-the-art in personal communication.

- Along with connectedness, weather forecasting has metamorphosed. Climate, as well as technological change, allows new weather variables — such as surface temperatures from as remote as the southern Indian Ocean and regular updates from the Pacific Ocean — to be mapped.

- Powerful computers mathematically simulate the weather based on these variables and extrapolate onto desired time frames.

Do we need to change our calendars?

- It made two key changes this year: reducing the definition of ‘normal’ rainfall by 1 cm, to 88 cm and, officially updating monsoon onset and arrival dates for many States.

- This was long due and constituted acknowledgement of the accumulated impact that global warming has been having on monsoon patterns, particularly for cities and States.

- The monsoon was arriving later in many places, had long weak spells, and lingered longer.

- This has already heralded thinking, in the agency, on whether India should move to a new monsoon-accounting calendar instead of the century-long tradition of June-September. This would signal a truly momentous break from the past.

- Just as COVID-19 is forcing introspection on the links that tie people, trade and ecology, it is also time for the IMD to incorporate the lessons from the new normals.

A VIRUS, SOCIAL DEMOCRACY, AND DIVIDENDS FOR KERALA

Focus: GS-III Disaster Management

Kerala’s Success in Flattening the curve

Though Kerala was the first State with a recorded case of coronavirus and once led the country in active cases, it now ranks 10th of all States and the total number of active cases (in a State that has done the most aggressive testing in India) has been declining for over a week and is now below the number of recovered cases. Given Kerala’s population density, deep connections to the global economy and the high international mobility of its citizens, it was primed to be a hotspot.

Why does Kerala stand out? Role of Social Democracy

Kerala’s much heralded success in social development has invited endless theories of its cultural, historical or geographical exceptionalism. But taming a pandemic and rapidly building out a massive and tailored safety net is fundamentally about the relation of the state to its citizens.

- Social democracies are built on an encompassing social pact with a political commitment to providing basic welfare and broad-based opportunity to all citizens. In Kerala, the social pact itself emerged from recurrent episodes of popular mobilisation — from the temple entry movement of the 1930s, to the peasant and workers’ movements in the 1950s and 1960s, a mass literacy movement in the 1980s, the Kerala Sasthra Sahithya Parishad (KSSP)-led movement for people’s decentralised planning in the 1990s, and, most recently, various gender and environmental movements. These movements not only nurtured a strong sense of social citizenship but also drove reforms that have incrementally strengthened the legal and institutional capacity for public action.

- The emphasis on rights-based welfare has been driven by and in turn has reinforced a vibrant, organised civil society which demands continuous accountability from front-line state actors.

- 3his constant demand-side pressure of a highly mobilised civil society and a competitive party system has pressured all governments in Kerala, regardless of the party in power, to deliver public services and to constantly expand the social safety net, in particular a public health system that is the best in India.

- That pressure has also fuelled Kerala’s push over the last two decades to empower local government. Nowhere in India are local governments as resourced and as capable as in Kerala.

- All of this ties into the greatest asset of any deep democracy, that is the generalised trust that comes from a State that has a wide and deep institutional surface area, and that on balance treats people not as subjects or clients, but as rights-bearing citizens.

How was this potential utilised?

A government’s capacity to respond to a cascading crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic relies on a very fragile chain of mobilising financial and societal resources, getting state actors to fulfil directives, coordinating across multiple authorities and jurisdictions and maybe, most importantly, getting citizens to comply. An effective response begins with programmatic decision-making.

Steps Followed

- Not only did the Chief Minister appeal to the sense of citizenship by declaring that the response was less an enforcement issue than about people’s participation, but also pointedly reminded the public that the virus does not discriminate, destigmatising the pandemic.

- The government was able to leverage a broad and dense health-care system that despite the recent growth of private health services, has maintained a robust public presence.

- The government activated an already highly mobilised civil society. As the cases multiplied, the government called on two lakh volunteers to go door to door, identifying those at risk and those in need.

- The key to effectiveness has been the capacity of state actors and civil society partners to coordinate their efforts at the level of panchayats, districts and municipalities.

WHY GOLD PRICES HAVE BEEN RISING BEFORE AND DURING COVID-19?

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Introduction to rising Gold Prices

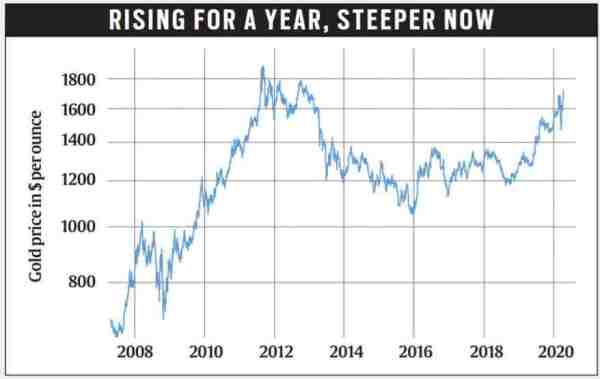

- Much before Covid-19’s impact reverberated across economies and led to a crash in global stock markets, gold prices had started their upward glide since May 2019 to culminate into a nearly 40 per cent jump in less than a year.

- The present gold prices in India are even higher, as they jumped from around Rs 32,000 per 10 grams to nearly Rs 46,800 per 10 gram during the same period, a nearly 45 per cent return.

- Since gold is mostly imported commodity into India, the depreciation of the rupee vis-a-vis the US dollar of around 7 per cent since last September pushed the gold prices in India even higher.

Why are gold prices rising?

- The expectation of recession sowed the seeds of the gold rally, and shutdown of major economies across the world, added momentum to the rising gold prices as a major global recession now looks certain.

- Any expansion in the paper currency tends to push up gold prices.

- Apart from this, major gold buying leading central banks of China and Russia over the last two years supported higher gold prices.

Trend in rising gold prices

- While gold by itself does not produce any economic value, it is an efficient tool to hedge against inflation and economic uncertainties.

- It is also more liquid when compared with real estate and many debt instruments which come with a lock-in period.

- After any major economic crash and recession, gold prices continue their upward run.

- The empirical findings suggest that gold prices fall with a rise in equity prices.

- Gold prices also move in tandem with heightened economic policy uncertainty, thereby indicating the safe haven feature of the asset, the RBI said in its latest Monetary Policy Report.

Can gold prices crash?

- Given the economic uncertainty, gold is expected to touch a new all time high, which will be over $1900 an ounce. In India, the prices will also be supported by any further weakness in the Indian rupee. Any sudden sale of gold holdings by central banks to tide over the economic crisis, and crisis in other risk assets prompting investors compensate their losses through sale of gold ETFs (exchange traded funds), are the key events could stall the gold rise.

- As an when economic recovery picks up pace investors will start allocating more funds to risk assets like stocks, real estate and bonds and pull out money from safe havens such as gold, US dollar, government debt and Japanese yen.

- As per historical trends, when equity and risk assets start an upward trend, gold typically falls significantly as was the case from 2011 till 2015.