Contents:

- Will COVID-19 affect the course of globalisation?

- A double whammy for India-Gulf economic ties

- A time for extraordinary action: State Investment

- Explained: Why children are less affected, more susceptible by COVID-19

- Donald Trump threatens to stop money to WHO

WILL COVID-19 AFFECT THE COURSE OF GLOBALISATION?

Focus: GS-III Disaster Management, Indian Economy

With several countries and regions locked down, will there be a redrawing of geographical boundaries?

- Much of what we saw in terms of global integration of trade and finance would suffer in the short run.

- When the world was hit by economic recession in 2008, trade dipped by almost 10% in 2009 when there was a 3% decline in global GDP.

- That’s roughly the relation between trade and growth. When there’s a boom, trade grows much faster than GDP.

- The World Trade Organization (WTO) has now estimated that in a worst-case scenario, global trade could dip as much as 32%, indicating the kind of dislocation they expect in large economies.

- It’s going to be a very different ball game — the first thing that will happen is countries will try to build themselves up.

How has it hit India and what can we expect as impact?

- In India we can see the disruption that is taking place — almost 50% of our trade is directly linked with the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) sector as even large players have sub-contracted to the smaller producers.

- So it is anyone’s guess what the impact is going to be on trade because of the disruption in production.

- Going forward, most economies, with the exception of China, are going to see a very different kind of dynamic as they will try to build up from where they would be in a few months’ time and then think in terms of how to integrate themselves again with other countries.

How could this impact Asia Pacific as a region and India in particular?

- UNESCAP has released its annual Economic and Social Survey on 8th April 2020 — what we are finding of course, is that the COVID-19 crisis is a challenge never seen before and it is going to be a bigger shock for the world economy than the global financial crisis which was only driven by a demand shock.

- This entails a demand and supply shock and it is still unfolding.

- It is now clear that many economies are going to shrink — developed countries as well as many in the Asia Pacific region that are highly dependent on tourism and commodities trading will also shrink.

- Commodity prices are at their lowest in the last 10 years.

Specifically, With respect to India

- There is a slight silver lining because of low oil and commodity prices as we are net importers and, also, since the government is not allowing a full pass-through of the lower global prices, it means that there is some fiscal space through commodity price reduction.

- Still, the disruption in work, especially in MSMEs that are the backbone of manufacturing, trading and services, is very serious.

Is COVID-19 set to reverse the trend of globalisation as we know it?

- The process of globalisation was already in retreat and last year, the term ‘slowbalisation’ was being used.

- World trade had never really recovered since the global financial crisis — from a 10% growth, it had been hovering around 1%-2%. Add to that the trade wars and the WTO talks process coming to a grinding halt.

- Now, with this pandemic, there is another recognition of the vulnerability that global economic interdependence creates.

- So some countries are facing difficulties in getting medical supplies, some find their manufacturing can’t run as value chains are linked with China.

- Countries will reconfigure their economies to look at import substitution with a greater clarity now, as the perils and pitfalls of overdependence on foreign supplies become clear.

- Import substitution, that had become a bad word, may be back in currency.

How different is China’s position?

- News has been filtering through that China’s manufacturing sector is back.

- Other countries will remain in a lockdown phase for at least another two months.

- So, if the Chinese get a lead in getting their act together, they are going to consolidate their position in the global economy further.

- However, China doesn’t really figure in the top of countries that have announced stimulus packages.

- Countries are going to be extremely wary of the superpower that China will become and would like to disengage.

Could this dampen movement of labour across countries?

- Once you talk of import substitution, you focus more on your domestic skills.

- The movement of personnel will follow the formula of economic needs.

- The first priority of every government would be to create jobs for its own people.

- In a high unemployment scenario, hiring expats won’t be in favour.

Could the role of WTO evolve in such a situation?

- Trade rules have worked best when the global economy is booming and isn’t facing a crisis.

- On the issue of subsidies for small industries, no country will like the WTO to be telling them what to do or what not to do.

- The agricultural subsidies issue is going to be junked.

- If the WTO rules are junked, then it’s a free-for-all situation.

Shall there be a rethink on existing multilateral and bilateral pacts?

- Countries cede a part of their sovereignty while getting into these trade agreements. In the last quarter of the twentieth century, we saw one driver of governance — market forces-oriented.

- But now, in major economies, governments have taken centre stage and depending on how long the pandemic drags on, the government will remain in the driver’s seat and markets will take a backseat.

- If governments have to do the heavy-lifting, then they want full force of their sovereign powers.

- The project of globalisation could settle at a new normal and it will be a very different WTO and trade governance framework, with different kinds of regional and bilateral engagements.

- India, of course, has already become a reluctant player and had, in a way, started disengaging.

- Other countries were more tightly knit together through pacts like the ASEAN.

- The European Union is already in tatters and it will be important to see the role of the European Commission and the European Central Bank in getting a decent stimulus in addition to what individual governments have done. NAFTA is already being rewritten.

- So going forward, much of the churning is going to get bigger in regional formations.

A DOUBLE WHAMMY FOR INDIA-GULF ECONOMIC TIES

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Why in news?

The Gulf region is at the epicentre of a perfect storm: apart from the COVID-19 pandemic, it also has an oil price meltdown.

The situation’s impact on bilateral economic ties needs to be anticipated and managed.

Oil prices in a tailspin- What happened?

- The region, especially Iran, has been mauled by COVID-19, and the figures are yet to peak.

- The pandemic has put nearly a third of the world’s population under some form of lockdown curbing the consumption of hydrocarbons, the mainstay of Gulf economies.

- A Goldman Sachs report published on March 30 estimated that COVID-19 had lowered the world crude consumption by 28 million bpd. The consequent oil glut began depressing the price.

- The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and other crude producers (OPEC+), however, failed to reach a production-curtailing strategy as Saudi Arabia and Russia, the cartel’s two biggest producers, held different views.

- As a result, OPEC+ unravelled with each producer chasing a higher share in a collapsing market.

- Consequently, the oil prices went for a tailspin having fallen by 55% during March to an 18-year low on March 30.

- Though the market has recovered since and a wider production-sharing compromise is in the works, the general outlook remains bleak.

Seriousness of the impacts

- In a rare joint statement on March 16, the heads of OPEC and the International Energy Agency (IEA) warned that developing countries’ oil and gas revenues will decline by 50% to 85% in 2020 with potentially far-reaching economic and social consequences.

- The economic outlook for the Gulf has indeed deteriorated, with Saudi Arabia’s fiscal deficit expected to cross 8% in 2020.

- The global economy is expected to have a recession induced by COVID-19 this year.

How does it Affect India?

- India’s economic ties with the Gulf states have two dominant verticals: the economic symbiosis and India’s expatriate community.

- Bilateral economic ties are strong: The India-Gulf trade stood around $162 billion in 2018-19, being nearly a fifth of India’s global trade. It was dominated by import of crude oil and natural gas worth nearly $75 billion, meeting nearly 65% of India’s total requirements.

- Some of these countries have large Indian investments and some have planned large investments in India.

- Second, the number of Indian expatriates in the Gulf states is about nine million, and they remitted nearly $40 billion back home.

- Both these intertwined pillars of India-Gulf ties have been affected by the recent maelstrom roiling the shared region.

- India being the world’s third largest importer of crude, a sharp and prolonged decline in oil prices helps its current account.

- However, this is not an unmitigated blessing. The Gulf’s lower oil revenues also presage decreased bilateral trade and investments as well as expatriates’ remittances — all of them adding to India’s current financial stress.

Impact on expatriates

- Oil is a cyclic commodity and the Gulf producers have long evolved a pattern to handle its periodic lows.

- They tend to tighten their belts and dip into their reserves. They also transfer the burden on to the last person in line, viz. the Asian expatriate.

- The fresh recruitment stops, salaries are either lowered or stalled, taxes raised and localisation drives launched.

- The net result is that a large number of expatriates return to their homes.

- This time there is an added complication of the pandemic, to which the Asian expatriates living in densely populated camps are particularly vulnerable.

- In case the pandemic worsens in the lower Gulf, panic-stricken, wage-deprived Indians may prefer to come back.

- This would create an exodus of epic proportions, the nearest example being the evacuation of over 1,50,000 Indians from Kuwait in 1990-91, albeit for political reasons, an event that upended India’s economy.

- Apart from creating a logistical nightmare of transporting millions of expatriates back, they would need to be resettled and re-employed.

Conclusion and Way Forward for India

- While hoping that the Gulf states are able to contain the pandemic and the oil shock, India needs to make some contingency plans in consultation with the individual countries.

- India should do whatever it takes to enhance their capacity to handle COVID-19 cases among the Indian expatriates.

- India’s missions there also need to monitor the situation and try to avoid panic among its nationals.

- In the longer run, it is quite clear that we need to find new drivers for the India-Gulf synergy.

- This search could begin with cooperation in healthcare and gradually extend outward towards pharmaceutical research and production, petrochemical complexes, building infrastructure in India and in third countries, agriculture, education and skilling as well as the economic activities in bilateral free zones created along our Arabian Sea coast eventually leading to an India-Gulf Cooperation Council Free Trade Area.

- Only then would we have sufficiently diversified the India-Gulf economic ties to protect them from such shocks.

A TIME FOR EXTRAORDINARY ACTION: STATE INVESTMENT

Focus: GS-III Indian Economy

Why is it a grave necessity?

- Even before the full impact of COVID-19 on the health of Indians is clear, the economic impact of the measures required to deal with the pandemic are already posing grave problems.

- The Indian economy was in dire straits even before COVID-19 reached our shores.

- Specifically, the lockdown and other movement restrictions, backed by scientific and political consensus on their inevitability, have directly led to a dramatic slowdown in economic activity across the board.

Technique of input-output (IO) models to assess

- Such models provide detailed sector-wise information of output and consumption in different sectors of the economy and their inter-linkages, along with the sum total of wages, profits, savings, and expenditures in each sector and by each section of final consumers (households, government, etc.).

- Crucially, it pays attention to intermediate consumption, namely consumption by some sectors of the output of other sectors (as well as consumption within their own sector).

- The key advantage of such a model is that it allows the calculation of the impact of any change in any sector in both direct and indirect terms, which has made this model somewhat ubiquitous in the computation of the economic impact of disasters.

- This also renders it well-suited to estimating the economic consequences of COVID-19.

Impact on various sectors

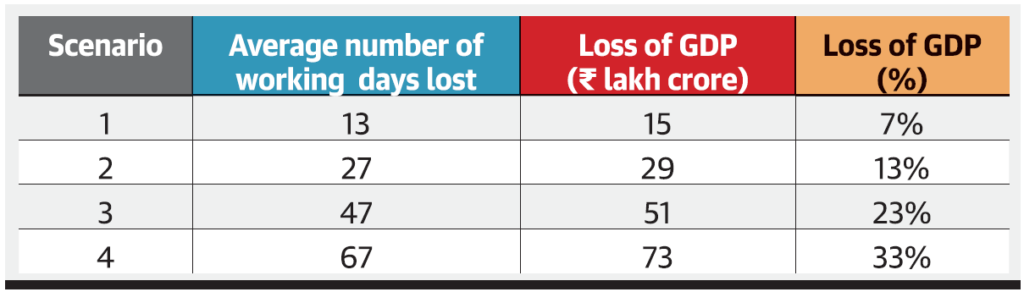

- The Model shows that the loss of GDP ranges from ₹17 lakh crore (7% of GDP) in the most conservative scenario, where the average number of output days lost is only 13, to ₹73 lakh crore (33% of GDP) in the most impactful scenario, where the number of days of lost output averages 67.

- In intermediate scenarios of 27 and 47 days of lost output, the GDP decline is ₹29 lakh crore (13% of GDP) and ₹51 lakh crore (23% of GDP), respectively.

Way Forward

- India needs a similar strategy- huge stimulus packages that developed countries have already started putting in place – as extraordinary times need extraordinary action.

- We need to compensate and pump cash into the hands of not only wage workers in the formal and informal sectors, and also into the livelihood activities of the informal sector, but businesses too need to be primed with handouts in the case of small and medium enterprises, and with a variety of concessions even in the case of larger businesses.

- It is critical to preserve the productive capacities of the Indian economy across the board.

- The annual budget of the current year, already passed, clearly cannot cope with such a massive effort and needs to be revisited by suitable parliamentary measures.

- Redistributing expenditure, seeking to keep the fiscal deficit “under control” as it were, through measures such as cutting back on government salaries, are unlikely to be helpful.

- Apart from sending the wrong signal to private sector employers, who have so far been exhorted to maintain salaries and wages during the lockdown, it is quite likely to lead to further reduction in demand since the government is the biggest employer in the country.

- Finally, one must note that the current crisis is not a transformatory moment for the Indian economy, even if the scale of the impact and recovery process will undoubtedly push the economy in new directions.

- But “greening” the economy or more radical transformative measures are not particularly relevant in its current state.

- What is needed is ensuring the key role of the state to lift up an economy that is in danger of being brought to its knees, and to restore some semblance of its normal rhythm, by an unprecedented scale of state investment.

EXPLAINED: WHY CHILDREN ARE LESS AFFECTED, MORE SUSCEPTIBLE BY COVID-19

Focus: GS-III Science and Technology

Why in news?

Research suggests that while everyone is susceptible to COVID-19, people over the age of 60 and children are particularly vulnerable.

Why children are less affected?

- In the early stages of the outbreak, it was found that COVID-19 was predominantly prevalent in adults over the age of 15 years, while the proportion of confirmed cases among children remained relatively smaller.

- Researchers found that it had been difficult to track the disease among children as they could not “clearly describe their own health status or contact history”.

- This, researchers said, contributed to the “severe challenge of protecting, diagnosing, and treating this population”.

- In China, children under the age of 18 accounted for about 2.4 per cent of all reported cases till publication of the study.

- To compare COVID-19 to other coronavirus outbreaks, during SARS in 2002-2003, the global number of children infected (between age groups of 4 months to 17 years) was less than 0.02 per cent of the total cases and no deaths were reported.

- Those severely affected accounted for over 7.9 per cent of the total cases of children.

- During the MERS outbreak, on the other hand children less than 19 years of age accounted for less than 2.2 per cent of all cases.

COVID-19 characteristics in children, according to research

- Citing existing epidemiological data, researchers say that 56 per cent of children demonstrated evidence of transmission through family gatherings and 43 per cent had a history of exposure to the epidemic site in China.

- In China, the first infant diagnosed with the disease was 17 days old. The youngest, probably, was a newborn confirmed to have been infected 36 hours after birth following a cesarean delivery.

- Significantly, the researchers noted that the incubation period in children was longer than in adults, which is approximately 6.5 days as compared to roughly 5.4 days in adults.

- Children infected with the virus show milder symptoms, a faster recovery, shorter “detoxification time” and a good prognosis as compared to adults, researchers found.

DONALD TRUMP THREATENS TO STOP MONEY TO WHO

Focus: GS-III Disaster Management, Indian Economy

Why in news?

On 7th April, President Donald Trump threatened to freeze US funding to the World Health Organization (WHO), saying the international group had “missed the call” on the coronavirus pandemic.

Trump’s views

- Trump said the body had “called it wrong” on COVID-19 and that it was very “Chinacentric” in its approach.

- He suggested that the WHO had gone along with Beijing’s efforts months ago to under-represent the severity of the outbreak.

- The American President declared he would cut off US funding for the organisation, then backtracked and said he would strongly consider such a move.

Objectives and Functions of WHO

It is stated in the constitution of the WHO that its objective “is the attainment by all people of the highest possible level of health”.

The WHO fulfills this objective through the following functions:

- By playing a role as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work.

- To maintain and establish collaboration with the United Nations, health administrations or groups and any other organisation as may be deemed appropriate

- To assist Governments, upon request, in strengthening health services

- To provide appropriate technical assistance and in the event of emergencies, necessary aid upon the request or acceptance of Governments

- To provide or assist in providing, upon the request of the United Nations, health services and facilities to special groups, such as the peoples of trust territories

How is the WHO funded?

- There are four kinds of contributions that make up funding for the WHO.

- These are assessed contributions, specified voluntary contributions, core voluntary contributions, and PIP contributions.

- According to the WHO website, assessed contributions are the dues countries pay in order to be a member of the Organization.

- The amount each Member State must pay is calculated relative to the country’s wealth and population.

- Voluntary contributions come from Member States (in addition to their assessed contribution) or from other partners. They can range from flexible to highly earmarked.

- Core voluntary contributions allow less well-funded activities to benefit from a better flow of resources and ease implementation bottlenecks that arise when immediate financing is lacking.

- Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Contributions were started in 2011 to improve and strengthen the sharing of influenza viruses with human pandemic potential, and to increase the access of developing countries to vaccines and other pandemic related supplies.

- In recent years, assessed contributions to the WHO have declined, and now account for less than one-fourth of its funding. These funds are important for the WHO, because they provide a level of predictability and minimise dependence on a narrow donor base.

- Voluntary contributions make up for most of the remaining funding.

Who funds WHO?

- As of fourth quarter of 2019, total contributions were around $5.62 billion, with assessed contributions accounting for $956 million, specified voluntary contributions $4.38 billion, core voluntary contributions $160 million, and PIP contributions $178 million.

- The United States is currently the WHO’s biggest contributor, making up 14.67 per cent of total funding by providing $553.1 million.

- The US is followed by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation forming 9.76 per cent or $367.7 million.

Allotment of Funds

- Out of the total funds, $1.2 billion is allotted for the Africa region, $1.02 billion for Eastern Mediterranean region, $963.9 million for the WHO headquarters, followed by South East Asia ($198.7 million), Europe ($200.4 million), Western Pacific ($152.1 million), and Americas (39.2 million) regions respectively.

- India is part of the South East Asia region.

- The biggest programme area where the money is allocated is polio eradication (26.51 per cent), followed by increasing access to essential health and nutrition services (12.04 per cent), and preventable diseases vaccines (8.89 per cent).